Though Catholicism is a minority religion in Nigeria—the northern half of the country is primarily Muslim; the south is primarily Christian, but most Christians belong to Protestant and African Independent Churches—Catholicism is by far the dominant faith among the Igbo people, whose homeland is a large section of southeast Nigeria. Catholic life in Igboland is exceptionally vibrant and vital, though not without tensions and paradoxes. Catholic practice there embraces the spectrum from traditional Roman Catholic devotions like the Rosary and Eucharistic Adoration to charismatic and Pentecostal forms of dancing devotion—and in some contexts combines all of these at once. In a wide variety of ways—some of which are often labeled by Catholics there as a problem, others definitely not—traditional ancestral cultures also shape the religious worldview of Catholics.

The designation Igbo embraces people from hundreds of very localized ethnic identities with their own local traditions, which complicates any attempt to speak broadly about Igbo culture. As one scholar summarized it, “One of the problems for most of the existing studies of Igboland is the tendency to generalize for the whole of Igboland on the basis of evidence which is valid for some Igbo areas only.”1 The articles here, while they apply in numerous ways to Igbo culture more broadly, focus on one city, Enugu.2 Given that Enugu city today is home to people who have gravitated from many villages over generations, many Igbo identities are represented here. Enugu residents whose ancestral villages are elsewhere are still linked to those villages for life. They are expected to return to their ancestral villages at least annually, and are returned there to be buried.

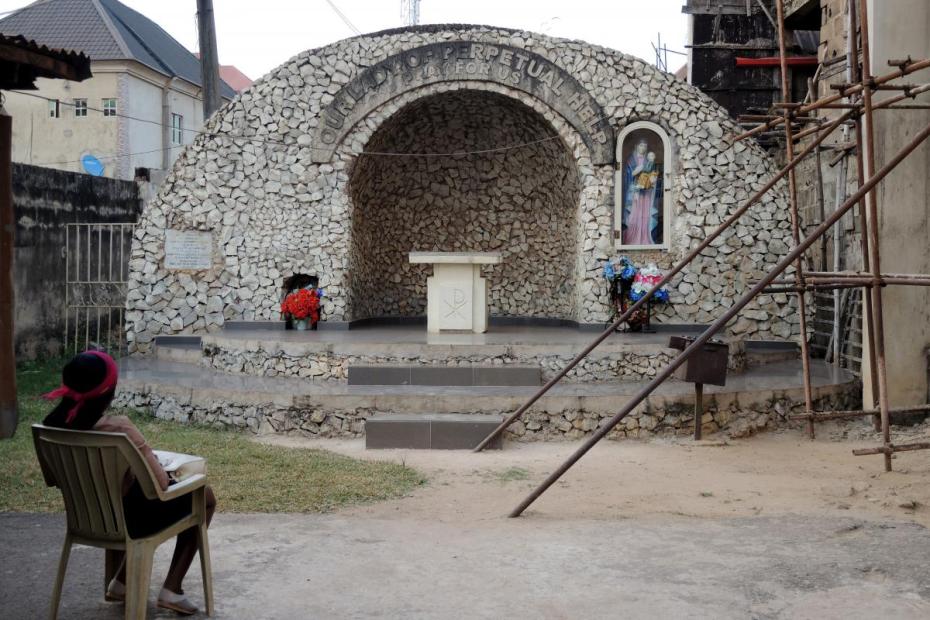

Enugu is a place where authority and charisma are both very clearly on display in Catholic life, and where tradition is alive in two senses: in the ordinary sense that Igbos mean when they refer to it, i.e. that pre-Christian Igbo traditions are honored; and in the Catholic sense, whether with the ringing of the Angelus at the market, or daily Rosaries, Eucharistic Adoration chapels, and even occasional Latin Masses.

Nigeria is old, with a long cultural history of its own, but in other ways a young country: as a nation-state, in Christian-historical terms, and especially demographically. Parents still value having many children, so the number of young people far outweighs the number of elderly. When people reference the conversion of their parents or grandparents, or when one sees so many young people at services, the Church feels like a young Church.

The Hearts of Jesus and Mary parish, where this report is centered, is at a growing edge of Enugu city. Founded as a new mission station in 2011, it held its first Masses in a garage. Parishioners eventually built a modest church, which is still being decorated as funds can be raised, and a rectory. For several years, the parish has been fostering two spin-off mission stations in its territory: Holy Spirit and St. Malachy. Even as Hearts of Jesus and Mary grows, its two mission stations are continually raising funds to buy land and build churches of their own.

Historical background

Read a brief historical background of the Igbo people’s rapid embrace of the Church and its remarkable transformation out of the ruins of the horrific Biafran war into a flourishing, Igbo-led local Church.

Igbo traditional religion

By all accounts, Igbo traditional religion continues to have a profound influence on Catholic life in Igboland, including among people who are deeply committed to the Church. As Jacinta Nwaka sums it up, “rather than defeating traditional gods, both Christianity and traditional practice exist side by side in Igboland and in the hearts of the Igbo people today, both struggling for supremacy.”3 Tension between traditional religion and Catholicism is a core theme of major works of Igbo literature, from Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958) and John Munonye’s The Only Son (1966) to Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus (2003), but we also need to pay attention to ways the two worldviews are not simply in conflict, but integrally interwoven.

Igbo traditional religious belief systems, though always localized in their particularities, are generally organized around three “pillars”: (1) a supreme being, Chukwu, the ineffable, all-powerful Creator of all that exists; including (2) the large number of minor gods and goddesses, both communal—those having particular influence over some aspect of a whole gamut of human occupations, elements of the natural world and life events—and personal, the chi, deities responsible for individuals’ well-being; and (3) the ancestors.4 Chukwu, the Creator, is a transcendent, omniscient being, so transcendent that “the main acts of religious devotion [are] directed to the divinities and ancestors who were believed to have active interest in the Igbo and their affairs.”5 Human beings’ relationships to the chi and the ancestors are binding and covenantal, a “web” that links past, present and future.6 Some of these minor divinities had pan-Igbo status, others were locally worshipped. Even among the relatively pan-Igbo deities, their character and status varied from community to community. Ubah, “The Supreme Being,” 94. The divinities and the ancestors are capable of intervening for good or ill in the lives of humans as they see fit. “Ancestors [and the minor gods] are neither intercessors or correlates of the Christian saints… but independent spiritual powers of much significance.”7 Ancestors and deities expect acknowledgement and sacrifices as a sign of respect, and can reward and punish according to the level of respect they receive. Priests offer sacrifices on behalf of the people, though ordinary individuals do so at their own small shrines. Diviners ascertain the causes of a range of problems as they arise, or are consulted to prevent them. A huge array of daily and seasonal rituals, life-stage rituals from initiation rites to funerals, forms of medicine and healing, rules for ordinary interactions, masquerades and civic forms, reinforce the traditional belief system.

“In most places you hardly see shrines now. Just a few in some communities,” interviewees claimed. In the early 1980s, anthropologist Mary Steimel Duru concluded that pre-Christian Igbo rituals were on the decline across three generations of Igbo people, but that beliefs were less affected. 8 Interviewees I spoke to said that belief in the minor deities had mostly disappeared, but had an odd way of popping back to life at times of high stress or during rituals of initiation.

Tradition in two senses

Focusing right away on the impact of Igbo traditional religion poses a risk of presenting an unbalanced image of Igbo Catholic life, so before focusing on indigenous aspects of Catholic life, it bears paying attention to the very many ways that Catholic visitors from other countries would have reason to feel very much at home. Seen from this perspective, Igbo culture has undergone a remarkable and rapid transformation in relatively short time. Igbo Catholic life today would be quite a puzzle to the traditional forebears of today’s Igbo Catholics.

“Tradition,” as I heard it used in Enugu, almost inevitably refers to the cultural and religious habits of pre-Christian Igboland. At the same time, Enugu is also a place where many traditional Roman Catholic practices are flourishing. A European traditionalist would be heartened to see the large number of clergy, religious women and seminarians in full habit, and to know that the diocesan seminary, one of a number of seminaries in the region, is the largest Catholic seminary in the world, home to more than 800 white-cassocked diocesan and religious order seminarians. He might also be surprised to see the level of deference to the clergy in matters of faith. He would be heartened to see the attendance at early morning Masses, catechism classes, “Block Rosary” meetings, adoration chapels, and at a wide array of lay Catholic associations. The fact that women consistently cover their heads at Mass, or that so many people wear scapulars or carry Rosary beads, or that so many people use traditional saints’ names—Veronica, Perpetua, Clement, Felix, Theophilus, Jude, Elizabeth and Stella come to mind among people I met, along with boys with Hebrew-biblical names like Ezekiel, Elijah, and Emmanuel—or that so many people begin or end the day praying the Rosary as a family, would make that Euro-Catholic traditionalist happy.9 Some parishes celebrate Mass monthly in Latin, in the contemporary Pauline rite, because it “is the language of the church,” and a way that they feel connected to that church, though parishioners don’t understand it well.10 Feeling connected to the universal Church is explicitly important to Catholics I spoke to.

The Church is not frozen in time, though. More contemporary manifestations of Catholicism are also quite evident here, particularly charismatic and Pentecostal-inspired forms of Catholic worship. Pentecostal churches have popped up all over, and many Catholics have taken to forms of worship that integrate charismatic prayer. Bible reading and interpretation is a regular part of my interviewees’ lives.

Catholicism has a very public role in the life of the community, not only through the many churches, hospitals, social services and ministries for the indigent, but also at public institutions. Faith extends more fluidly into the workplace than in many parts of the world. At work, people feel at ease displaying Catholic images. “You can always tell who is Catholic” at work, one woman said, because people bring symbols of it to work. Many workplaces, including government ones, invite priests into the workplace to say Mass fairly regularly. In the public market, people reported, a bell rings at 6 a.m., noon, and 6 p.m., and transactions stop for Catholics to pray the Angelus.

Discussions with lay Catholics in Enugu showed a whole range of ways that people prayed, from relying overwhelmingly on official, formulated prayers such as the Rosary, St. Jude Prayers, or the Legion of Mary’s Catena—“A good many of us memorize our prayers, so we have a formula,” said one woman—to free-form prayer in charismatic services. Marian devotion is thick and widespread, but does not overshadow devotion to Jesus. Saints are called upon as protectors and intercessors, but no saint seems especially prominent. Of his prayers, one man said, “You first of all invoke the Holy Spirit: ‘Come, o Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of your faithful,’ after which you say the Hail Mary, then the Rosary.” In the charismatic movement, devotion to the Holy Spirit is explicit and powerful, as is devotion to Jesus and the Father, but those services often also include the Rosary.

The coexistence of two kinds of traditional devotion—Igbo and Catholic-European—may seem paradoxical in light of the other ways that Enugu has modernized and wants to be modern. Irish missionary Catholicism surely left its legacy, but the reasons it endures are complex. One Igbo pastor said that he thought that morning family Rosaries, Adoration and daily local Masses are successful precisely because they fill a gap left from traditional morning devotion to local gods at household shrines. An Igbo theologian suggests that traditional Catholic devotions have taken on particular strength in recent decades not as a reaction to modernity or to the changes of Vatican II, but because they stood out as distinctively Catholic bulwarks against the Pentecostalist churches that began to pop up in Igboland in the last thirty years.11

With that context in mind, we can explore more fruitfully some of the other ways that Igbo traditional culture also makes Catholic life here distinctive. In Igbo traditional religion, “Events at the material level are mere manifestations of what has been pre-determined at the spiritual level... Therefore, life is fraught with a hidden warfare in which inimical spiritual forces essay to control man.”12 The thinness of the curtain separating the spiritual and material realms continues very much to shape Igbo Catholics’ worldview.

Ancestors

Without doubt, Christianity ruptured relationships between generations of traditional and Christian believers, as the great Igbo literary works cited earlier explore. Still, Duru reported in the 1980s that belief in the power of ancestral spirits had only been moderately weakened.13 Respect for ancestors remains a powerful ethical imperative. Ancestors are called upon as respected friends during kola nut rituals to welcome guests, and at many feasts and special occasions.14 Children are educated to be obedient to parents more than to be independent. Large, expensive funerals are owed to deceased family members.

Such respect is not an abstract moral duty. It is the outcome of an enduring, powerful belief among Igbo people that the actions, failings, or displeasure of their ancestors can still easily come home to impact the living. “[T]he success or failure of men’s activities does not just depend on their own efforts but is linked with the disposition of those spirits towards them.”15 What C.N. Ubah wrote decades ago still has resonance: “It is held that ancestors who receive poor sacrifices during… festivals are ridiculed in the spirit world, and they will not take kindly to such a disgrace… And here in the material world, anybody who offers to his ancestors a cock when he could easily afford a goat is ridiculed by fellow men for his miserliness.”16

Witchcraft

Fear of witchcraft and of demons is an equally powerful reality. In the 1980s, Duru reported that of all types of traditional beliefs, beliefs in the efficacy of witchcraft had not been weakened at all.17 Interviewees in 2019 reported that their fellow Igbos’ first tendency when they encounter misfortune is to turn to “persons” to explain why the problem came their way. “Persons” signals two sources: ancestors, or persons who wish someone well and resort to witchcraft to achieve it: “I’m walking and I fall—people are after me, maybe from the village,” a man explained.

Witchcraft is not simply the work of specialists, but can be carried out by ordinary people using juju, or charms. City people associate it with villages.18 “To believe in charms: we do,” said one well-educated Catholic man. Priests also said that they believe in witchcraft. It is not a delusion or a fantasy, one said, but a force that can release deadly power, and that needs to be prayed against. “I must do everything I can to liberate people from these powers.”

In a universe so full of such powerful forces, the phrases encountered most frequently were “My God is more powerful than,” or “Almighty God, mightier than all gods,” rather than “There is no other God than...” God is called on to overpower and protect from other powerful spiritual realities. Video from Fr. Mbaka’s Adoration Ministry shows an example of that sort of prayer, as do accounts of Fr. Paul Obayi, a prominent charismatic priest in Nsukka, exorcising “diabolic deities.” Fear of witchcraft draws people to the Christian God, certainly, but some interviewees say that at times of fear, people can too often be drawn away from God to these other fearsome powers.

One highly educated Igbo Catholic asserts that this may be a reason why Rosary beads and scapulars are important here—not only as aids to prayer and signals of religious devotion, but also as protection from evil spirits. They replace older traditions of wearing threads and charms as protection in traditional religion.

Igbo tradition also relies on dibias, or diviners and seers, who have the capacity to “obtain information which is not available by direct sensory perception,” whether about events in this world or the spiritual realm. Their role, which also includes healing, remains prominent in many places, though many Christians profess to reject it.19

“Spiritual problems”

Interviews with a number of catechists and parish priests posit that a major reason people come to them for prayers or guidance is for “spiritual problems.” At Ugwu-Di-Nso, "Holy Hill" retreat center, priests also said that it may be the major reason people come there. People at Fr. Mbaka’s Adoration ministry said the same.

“Spiritual problems” does not refer to problems that arise from one’s own inner spiritual failings, but from the external causes identified above: ancestors or witchcraft. The occasion for this is often a universal human problem—sickness, financial struggle, failure in business, family problems, inability to conceive, etc.—but the cultural frame is that these are fundamentally “spiritual problems” at root.20 They may arise from a personal failure to respect the ancestors, but more often, the problems are perceived to mean that this person is paying for sins committed by their forebears. In that sense, they are not precisely “ancestral,” because only good forebears can become “ancestors,” but they are caused by other forebears who have sinned and whose misdeeds have come to roost. That worldview is deeply traditional, and perhaps exacerbated by the rupture between non-Christian and Christian generations, but it is reinforced by biblical injunctions such as Exodus 34:7, where God promises to visit “the iniquity of the parents upon the children and the children’s children, to the third and the fourth generation.”21

Igbo believers are no less aware than anyone else of their own sinfulness, but in terms of “spiritual problems” perceive an added reason for concern. We “need God’s help to break through,” one told me.

Reincarnation

Traditional religion holds that the spirits of a good person are able to return to the material world through their own progeny. Duru’s 1980s study reported that beliefs in reincarnation were only moderately weakened,22 and interviews in 2019 suggested that belief in reincarnation resonates. This is not because people had not been taught about the Christian view of the afterlife, people make clear, but often occurs because people see evidence that reinforces the traditional worldview, such as when individuals see characteristics of a deceased uncle or father in a child. “Sometimes they believe it so much that they go to the level of giving the same level of respect to the child that they would give to the father,” one said. A priest reported that back in his village, “I’m given preferential treatment in my maternal home, because they say that I resemble my grandfather. So whenever I go there, my grandmother can leave everything… because she sees her husband in me [though] the husband is no more.” She is Catholic, and she knows the catechism, but “can’t separate herself from what she sees. Her husband was one of the early catechist/teachers, and [my role] helps reinforce what she always saw when she looked at me.” She is not the only one there who sees things this way: “People [there] don’t know my Igbo name. They call me by my grandfather’s [Igbo] name. And my baptismal name is actually the same as my grandfather’s name: Raymond.” Traditional religion’s cyclical conception of time, manifest in reincarnation, seeps into the linear Christian view of creation and salvation.

Naming

The enhancement of Catholic traditions by Igbo ones is manifest in traditions around names, and the ritual for conferring names. “Igbo names are not mere tags to distinguish one thing or person from another; but are expressions of the nature of that which they stand for.”23 Igbo and Catholic names are used to remind us about God.

Kola nut

The entries here do not allow for a rich enough accounting of the daily rituals that define the fabric of Igbo life, or of seasonal rituals like harvest festivals or masquerades. One important ritual bears highlighting, not least because of the ways it overlaps with the core Catholic ritual, Eucharist.

Breaking, sharing and eating a kola nut is an essential traditional means to welcome guests and in a range of other contexts. As Catholics and other Igbo people practice it, the ritual always begins by invoking the ancestors. One Igbo Catholic priest and scholar says, “if split and partaken of by others, [the kola nut ritual] constitutes a pact of loyalty and of communion.”24 To refuse it is to give reason to the group to believe that you harbor malice. Many Catholics have thought carefully about how to adapt the ritual, and think of it as a crucial cultural obligation to perform it.25

Tensions and reconciliations

Like all cultures, Igbo culture holds together a variety of values in tension, beyond those elucidated here. These tensions are sometimes reconciled, sometimes in the forefront. A few that can’t be fully developed here still stood out as significant themes:

- While traditional influences have been emphasized in this article, contemporary influences should not be underestimated. One of the young men in Enugu asserted, “We are not the old green Africa of the past. We are westernized. The old stories of the past don’t get told.”

- Seminaries, convents, Masses, and prayer meetings are full, and Pentecostal Christianity has made big strides here. Catholic as Enugu is, there is still a surprising amount of movement by laypeople among denominations. Some people even attend both churches on a single Sunday.

- Clergy are highly respected figures, yet in the eight months before this research, nine priests had been kidnapped in Enugu state for ransom. Two of them were murdered. Enugu stands out both for its hospitality and for the danger posed to all by an epidemic of highway kidnappings.

- Some people critique a local tendency to go to God to seek miraculous, material relief, but many others characterize Igbo people as entrepreneurial, businesslike, always getting out and hustling to survive, hardly acting like people who are just waiting for divine intervention. “You never see an Igbo man begging. We are hustlers. Lots of people struggle, but unlike [other parts of the country], there are no beggars here” said one. Interviewees regularly described the Igbo people as “naturally” or inherently religious. Any critiques articulated were not about whether to be religious, but about how people should address their religious longings.

At moments, the relationship between traditional religion and Catholicism seems like a challenge, but interviewees also reject the idea that they should or could turn back on their own culture. They are proud and grateful to be Igbo, and the ones I met all managed any seeming tensions seemingly to their own satisfaction. One deeply committed Catholic man didn’t hesitate to report that he participates in masquerades in his village, though these have been a site of real tension for some Catholics. “You cannot just abandon it. That is our life.” “If there are parts of traditional medicine that contradict Christianity, like charms,” he continued, “you remove that part, and make it a kind of entertainment. Traditionally, if a masquerade came, women, men and children would not come out. But today we do it as an entertainment, and people can come out and see it.”

More frequently, perhaps because they are stripped down into entertainment, adapted as non-religious “culture,” or Christianized, the tensions are reconciled. Scholars assert that in Igbo there is no word for “religion” as a distinct category of thing, separate from the rest of life.26 But Christian belief has inserted that idea, leaving ordinary people to say that they extirpate the “religious” parts from a ritual, and leave the “other” parts in place. Catholics reconcile a different way, too: though scholars have argued that it does an injustice to the traditional worldview to equate the gods and chi with patron saints, I heard interviewees do just that to explain how showing devotion to ancestors is a way of honoring the communion of saints.

“What else should be said?”

Asked what readers outside Nigeria should know about them, interviewees stressed two things that don’t fit well in the prior narrative, but warrant inclusion. Many people stressed “the suffering we are enduring”: how much their experience and thinking is filtered through—though not defined by—struggles over poverty, corruption, and exploitation.27 One man, Ezekiel, described life for Igbo people as “unrelenting struggle and strategizing.”

Second, people often asked that the story of tension they experience with Northern Fulani tribes people not be left out. Western readers have read about Boko Haram attacks in the north, which are a concern, but my interviewees had in mind tensions closer to home, as Fulani tribes people move south into Igbo lands with their cattle. Many interviewees said that it was an untenable situation, and attribute many of the kidnappings to the northerners. Attacks on Churches are more frequent, and kidnapping of Catholic priests for ransom has reached epidemic proportions. Catholics often expressed anger and frustration at the attacks, by what they saw as the government’s non-responsiveness to it and by the international community’s indifference.

- 1C. N. Ubah, “The Supreme Being, Divinities and Ancestors in Igbo Traditional Religion: Evidence From Otanchara and Otanzu,” Africa: Journal of the International African Institute/Revue de l’Institut Africain International 52, no. 2 (1982): 90. Ogbu U. Kalu, among others, grappled with the same problem, and tried to address it in his history of Christianity in Igboland by dividing Igboland into eight “culture areas,” but even he saw diversity within those groups. Ogbu U. Kalu, The Embattled Gods: Christianization of Igboland, 1841-1991 (Trenton & Asmara: Africa World Press, 2003), 10, 30. One of the challenges for this writer was the range of ways that interviewees responded to questions about how culture impacts faith. Answers referring to “we Africans” were common, as were answers related to Nigerian identity, Igbo identity, and occasionally, to “my people,” i.e. to village or tribal identity. The challenge was to sort them out to see which was most salient for interviewees. The answer to this varied and was of course influenced deeply by my own position as a White American. I always asked people to describe what was true at the level of local identity, and how that might compare even to other Nigerian identities, though this proved hard for many to describe.

- 2While this article depends on a variety of published resources by Igbo scholars, it is framed around research in Enugu, with ventures up to Nsukka, over the course of 11 days in December 2019. I am indebted to Fr. Stan Chu Ilo, PhD for opening many doors there, and for his advice and feedback; to Fr. Paulinus Ike Ogara, an author on many topics, for his patient guidance and insight on the ground; and to Fr. Theophilus Enebechi, catechist Odoh Basil A., and the people of Hearts of Jesus and Mary Parish and its mission stations for their warm hospitality.

- 3Jacinta Chiamaka, Nwaka, “The Early Missionary Groups and the Contest for Igboland: A Reappraisal of Their Evangelization Strategies.” Missiology 40, No. 4 ( 2012): 419.

- 4Ubah, “The Supreme Being,” 90. For a typology of the deities, see Kalu, The Embattled Gods, 29-52.

- 5C. N. Ubah, “Religious Change among the Igbo during the Colonial Period,” Journal of Religion in Africa 18, no. 1 (1988): 72. Ubah writes in the past tense, but there are still people who believe primarily or exclusively in the traditional system. Speaking of religiosity in Onitchara and Otanzu, not too far south of Enugu, Ubah writes elsewhere, “Chukwu does not require people to extend their resources in the effort to worship him, and unlike God in Christian theology is not jealous of people’s association with other spirits.” Ubah, “The Supreme Being,” 92. George Nnaemeka Oranekwu challenges that description of transcendence and distance in The Significant Role of Initiation in the Traditional Igbo Culture and Religion: An Inculturation Basis for Pastoral Catechesis of Christian Initiation (Frankfurt: IKO Verlag, 2004), 80-81.

- 6Nwaka, “The Early Missionary Groups and the Contest for Igboland," 416.

- 7Kalu, The Embattled Gods, 46.

- 8Mary Steimel Duru, “Continuity in the Midst of Change: Underlying Themes in Igbo Culture,” Anthropological Quarterly 56, no. 1 (1983): 6.

- 9To be sure, almost all of these people also have a traditional Igbo name.

- 10At Hearts of Jesus and Mary parish, for example, the first Sunday of each month is celebrated in English, the second and fourth in Igbo, and the third in Latin, with an English or Igbo homily. Some parishes said they don’t, “because people don’t understand it, and they will just feel sleepy, and the aim will be defeated.”

- 11Stan Chu Ilo, personal conversation. Ilo also recognizes the historic role of Irish missionaries in bringing these devotions, and the enduring role of the Block Rosary movement in continuing that devotion.

- 12Kalu, The Embattled Gods, 31.

- 13Duru, “Continuity in the Midst of Change,” 4.

- 14I experienced this when a group I was with was welcomed by a bishop, using the kola nut ritual that remains an important cultural tradition. Hospitality and proper welcome remains very important in Igbo culture.

- 15Ubah, “The Supreme Being,” 91.

- 16Ubah, “The Supreme Being,” 102, 104.

- 17Duru, “Continuity in the Midst of Change,” 4.

- 18Shortly before this research, a conference at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, addressed the topic of witchcraft. The mere existence of the discussion proved to be a huge public controversy. In his unpublished lead paper, “The Wealthy are No Witches,” (November 26, 2019) Prof. Damian Ugwutikiri Opata discussed the powerful hold witchcraft belief has in contemporary Igbo life, even as he claimed that this was a Christian misinterpretation of traditional Igbo cosmology, which has “no conceptual equivalent of the Christian Devil.” He argued that witchcraft is always assigned to be the work of poor villagers.

- 19Opata, “The Wealthy are no Witches.”

- 20On the Igbo belief that “the cause of sickness is always spiritual,” and the role of religious healing to overcome that, see Stan Chu Ilo, “Searching for Healing in a Miraculous Stream: The Fate of God’s People in Africa,” in Wealth, Health, and Hope in African Christian Religion: The Search for Abundant Life, ed. Stan Chu Ilo (Lanham, MD: Lexington/Rowman and Littlefield, 2018), 45-79. The chapter contains some excellent extended interview excerpts about people’s belief in “spiritual problems,” though the denominational tradition of the interviewees is not always indicated.

- 21Exodus, 34:7, New Revised Standard Version.

- 22Duru, “Continuity in the Midst of Change,” 4.

- 23C.O. Obiego, African Image of the Ultimate Reality: Analysis of Igbo Ideas of Life and Death in Relation to Chukwu (Bern/Berlin: Peter Lang, 1984), 32.

- 24A variety of these rituals are well described in George Nnaemeka Oranekwu, The Significant Role of Initiation in the Traditional Igbo Culture and Religion: An Inculturation Basis for Pastoral Catechesis of Christian Initiation (Frankfurt: IKO Verlag, 2004), 71-80.

- 25The bishop of Nsukka, Godfrey Igwebuike Onah, kindly shared it when he welcomed me and a group of visitors. I also experienced it at a parish mission station after Mass.

- 26Austin Echema, Igbo Funeral Rites Today: Anthropological and Theological Perspectives (Munster: LIT Verlag/Piscataway: Transaction, 2010), 10.

- 27Corruption is regularly described in Enugu as the bane of Nigerian society, but as one scholar describes it, it is not an outgrowth of Igbo traditional society. “The current trend in our political life where some leaders convert public property into personal property is not an Igbo heritage.” In Igbo traditional society, men gave from their own abundance to purchase status. Wealth was “viewed in Igbo society as a means of achieving prestige; and prestige is the reward which society bestows on those social climbers who use their wealth in ways approved and most esteemed by their neighbors and communities… Among the Hausa, political office led to wealth, among the Igbo, the acquisition of wealth led to political power.” Victor Chikezie Uchendu, “Ezi Na Ulo: The Extended Family in Igbo Civilization,” Dialectical Anthropology 31, No. 1–3 (2007): 193, 203, 216.