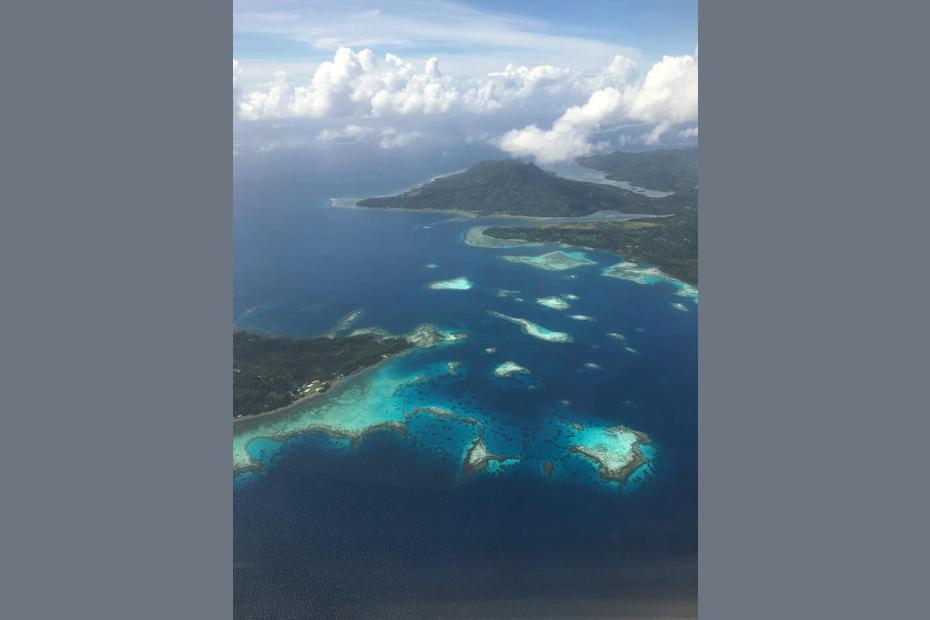

In common parlance, Chuuk refers to both an island group within the Micronesian coral atoll known as the Chuuk Lagoon, and a larger group of islands united as the state of Chuuk. The state of Chuuk, the most populous of the four states that constitute the Federated States of Micronesia, comprises at least 40 inhabited islands, including 16 in the Chuuk Lagoon. The Chuuk Lagoon itself comprises more than 2,000 square kilometers within its coral reefs. Many of Chuuk state’s other “Outer Islands” are an overnight boat ride away in open ocean.

The islands comprising the state of Chuuk share a common history. Though pre-colonial political power was quite localized and fragmented, and conflict is said to have been frequent, the islands were engaged in relationships of mutual dependence. During the colonial and post-colonial eras since the late 19th century, they have shared a common political history. They also have a good deal in common culturally, though the specifics often differ from island to island. Chuukese, other Chuukic languages and English are the primary languages in Chuuk state today. The latter serves to overcome problems of intelligibility between different Chuukic languages, and arises from years of post-World War II American governance of the islands.

The entries on this website focus on research on two of the islands in the Chuuk Lagoon: Weno, a high island near the center of the Chuuk Lagoon, which is the capital of Chuuk, its most populous island (pop. 14,000), and home of the main port and airport; and Fono, a much smaller island nearby.1 Both are physically close and share much in common culturally, but have different levels of development. Weno is the more Westernized of the two, though it is not highly developed economically. The Chuuk Lagoon is a destination for divers, who constitute most of the tourists who come to Weno’s three small hotels. Fono (pop. 400), a short boat ride from Weno, is more traditional. Concrete, plywood, or tin-scrap houses have replaced nipa huts, but most people live in subsistence fashion, largely off the produce of the land—breadfruit, taro, coconuts, bananas, papaya—and of the sea. Traditional cultural norms are more intact there. The entries on this site also make reference to Catholic life and practice on Pulap (or Pollap), a coral atoll that is one of Chuuk’s most distant Outer Islands, based on accounts by anthropologist Juliana Flinn.

For years, half of the population of Chuuk identified as Catholic, the other half as Protestant. That has shifted slightly in the last two decades. In the 2010 census, 55% of residents of Chuuk Lagoon islands identified as Catholic, and 44% as Congregationalist Protestants, though in Weno and Fono the Congregationalists were slightly in the majority. Only 0.1% of people on Weno, and none of the people on Fono, identified as “no religion” in that census.2

Historical background

Islands in the Chuuk Lagoon were first settled some 2,000 years ago by peoples who migrated great ocean distances in canoes. Extensive settlement began in the 14th century, and probably occurred in waves. These inhabitants were linked to other islands in networks of exchange and mutual dependence, but apparently did not venture out much themselves. People from other atolls came to them.3 According to the accounts and evidence available, “the social structure and the religions of the islands [were] fragmented and highly localized,” and villages were often engaged in conflict.4

Scholars have gathered a variety of accounts of pre-colonial religion, though the accounts vary in important details, whether because of the diversity of local practices, or the fact that they were already fading when they were recounted. “The Chuukic islands never developed the hierarchical priesthoods found in [the other Micronesian states of] Kosrae, Pohnpei, and Yap. Chuuk religious specialists, by and large, remained part-time diviners and healers working at the lineage or small atoll level.” 5 That should not be interpreted to mean that religious activity was lacking. In the popular imaginary, great gods inhabited the sky and sea, and there were a variety of creation narratives to explain human existence.6 The world was populated by spirits, including demons and ghosts of the dead, all of whom, particularly when offended, impacted the well-being of the living.7 “[H]ealing, canoe-building, navigating, dancing and weaving were all spirit-given knowledge, upon which people had to depend to complement their own human talent, skill and artistry.”8

With a reputation among seafarers as “the terror of the Carolines” for having violently repelled foreign ships and for localized conflicts, Chuuk was one of the last island groups to be impacted by a sustained Western presence.9 Though the islands had been claimed by Spain since Spanish ships explored the region in the 16th century, traders, missionaries and soldiers failed to establish settlements. Spanish trade routes ran to the north, and the islands were not of interest for exploitable resources.

American Congregationalist Protestant missionaries made the first inroads in the 1870s, alongside a few traders. Germany took possession of the islands in 1899, and managed to subdue and pacify local warring factions.10 Only in 1912 did German Capuchins, the first Catholic clergy, arrive as missionaries.

Lay catechists played an essential role in the spread of the faith, often preceding priests to islands and securing invitations for them. The early mission was particularly successful in the Mortlock atoll, about 200 km from the Chuuk Lagoon. That led to success in the Chuuk Lagoon later. 11 That stopped when the German Capuchins were expelled after Japan took possession of the islands following World War I, but Spanish Jesuits were allowed in two years later. A number of lay catechists kept the faith alive in the interim, and continued to play an important role thereafter.

Though Catholicism and Protestantism came late to Chuuk, the islands became almost entirely Christian in a relatively short time. On islands that had once been fiercely resistant to Christianity, the catechists and Jesuits made surprisingly rapid progress spreading the faith. The missions were poor and struggled financially, yet on Weno, for example, several people a day were baptized for months at a time in the late 1920s, until half the island was baptized. Marian and Sacred Heart visions were so frequent that “the Chuuk area soon came to be known as the ‘Islands of Apparitions.’”12 Catholicism only arrived on the Outer Island of Pulap (Pollap) in the late 1940s, on the impetus of a lay catechist from the Mortlock Islands. Today it is entirely Catholic.13

World War II was a time of great hardship in the Chuuk Lagoon, which was home to major Japanese military installations and a huge fleet of ships, many of which were sunk when Americans took the lagoon in a days-long battle. American Jesuits arrived after the war, beginning a period of expansion that included the construction of several schools, including two led by Mercedarian sisters and a high school that still draws students from the whole of Micronesia. The United States governed Chuuk state after the war, until the four states today comprising the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) signed a Compact of Free Association with the United States that took effect in 1986. The compact gives the United States a military role in the FSM, and gives Chuukese people a right to live and work in the United States.

According to Ward Goodenough, who studied pre-Christian religious traditions in Yap beginning in 1947, “Pre-Christian ritual continued to be practiced by many of Chuuk’s people through the first two decades of the twentieth century. By the end of World War II, however, nearly everyone professed to be Christian, at least nominally, though some of the traditional rituals continued to be done privately, such as those relating to spirit mediums, divination, diagnosis and treatment of sickness, and housebuilding and other crafts.”14 In the 1960s, he claimed, these practices were much diminished, but “concern with the spirits of deceased relatives… continued to be strong.”15 On Pulap, similarly, Flinn saw that traditional activities and medicine endured, but without the magical songs, chants or formulas that once accompanied them, but “even the educated continue to believe they can communicate with the spirits in dreams.”16

A culture of respect and deference

When asked to sum up Chuukese culture, Chuukese inevitably start with words like “respect” or “deference,” and point to the role that extended family and sharing play in daily life. One interviewee noted, “Respect is still very strong today… once [elders] give the order to do something, we have to do it.” That’s true not just in reference to parents, but also towards “the elders of our clan. If they say we have to go fishing, we have to go.” Obligations to elders in one’s mother’s family take special precedence. Though the right is less frequently exercised today, elders in families have final say over children’s potential spouses.

Modesty is important. To draw attention to oneself is regarded as a form of arrogance that puts oneself, not the community, first, and is disrespectful. Self-expression—or any effort to try to stand out from the crowd—is looked down on. Everyone thrives, people believe, when people know their place in the village and lineage, and act in the group’s interest.17 Social norms strongly discourage expression of anger, and in general Chuukese are remarkably calm people. Chuuk is not without conflict and social tensions, which can burst forth spectacularly when men have been drinking. But Chuukese culture places a tremendous priority on reconciliation, facilitated particularly by traditional, in tandem with Catholic, values and rituals. In contrast to the degree of conflict that is commonly said to have engulfed pre-colonial Chuuk, contemporary Chuukese culture places a premium on achieving harmony and stability. When that harmony is fractured by violence or any death, Chuukese have rituals designed to restore it.

Interviewees consistently described Chuuk as a place where people are friendly, and where, though people often live at a subsistence level, “You do not have to worry about hunger. Most Chuukese give food. You come by my house, and I call you to come eat. That’s our culture. Come and rest and drink water.” Sharing food in abundance, Hezel suggests too, is the way Micronesians show love, rather than through strong emotional engagement.18 One interviewee worried seriously that this propensity to share freely was diminishing, seriously undermining Chuukese society, but to this outsider, the propensity to share food generously was repeatedly apparent.

Though Chuuk is comparatively close to Guam in the Pacific, Chuuk does not embrace the same Spanish-inflected form Catholic life as Guam’s Chamorros. Chuukese who knew both Chuuk and Guam well suggested that though they shared some cultural elements in common, such as respect for elders and for the dead, there were real differences. Devotion, they said, doesn’t run as deep on Chuuk as on Guam. The claim is puzzling at first, given that almost all Chuukese identify as Christian, and the vast majority seem to participate in religious services. It seems to refer instead to the quality of the engagement, the relatively impassive style of worship that contrasts to the sometimes more emotional investment that Chamorros bring to worship. Likewise, Chuuk does not embrace the same traditions of processions, promesas, or techas (traditional women prayer leaders) that mark Catholic life on Guam. Chuuk has more in common with Yap, particularly in terms of the incredible depth of emphasis on respect and deference that both cultures share, but as that account shows, there are still also notable differences.19

Everyday religion, more than grand seasonal feasts, is the foundation of Catholic life in Chuuk. People enjoy singing, and love the celebration of Christmas. Even weeks before Christmas greeted each other with Merry Christmas on the street. But it is in daily life—weekly Rosaries or prayer services—that Catholic life is practiced, typically in the absence of a priest. Priests are welcomed and honored, but scattered villages and smaller islands depend not only on the islands’ many married deacons, but also very much on lay catechists. Catholic practice seems to be as small-scale, localized and unspectacular (compared to some other cultures) as pre-Christian religion is said to have been. Many small island communities are long accustomed to being visited only occasionally by a priest.

Asked about major religious feasts during the year that were especially meaningful, a number of people pointed to Diocese Day in early February, the commemoration of the establishment of a Catholic diocese in Micronesia, or to the parish’s annual celebration of the anniversary of the parish’s founding, or the day of its patron saint, which could include Mass and a procession, and a feast that could include a roast pig. On the Outer Island of Pulap which Juliana Flinn studied, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception was a major feast of the year, rivaling Christmas.

Realms of authority

In contemporary Chuuk, people’s lives are shaped by three different realms of authority—the traditional realm, particularly manifest in norms around family and chiefly authority; the realm of religion, important on islands where almost everyone identifies as Christian; and the realm of modern government. “Although the domains are expected to operate in harmony with each other, they must also nonetheless remain distinct.”20 There are days and times for church events, others for traditional or family events. Church leaders have space to operate and, insofar as they achieve consensus to do so, to follow somewhat distinctive rules for religious worship and encounters.

In all of the realms, respect and deference are paramount cultural values. Even a chief is expected to fulfill his duties modestly. The family and worship sections of this website describe a number of ways that deference plays out. The political realm is ideally supposed to be indifferent to rank in a bureaucratic way, but defers in many ways to the traditional realm including, if the families work it out, on the instances of informal family reconciliation in the wake of violence. “This deference is part of a larger system of respect and ranking such that everyone—male and female—defers to someone else.”21

Chuukese people are quite conscious of the boundaries and interaction between the realms of traditional culture, Christianity, and politics.22 The logic of traditional culture and Catholicism sometimes penetrate one another. People want these to work together, but are also aware of the ways that each poses a distinct realm with its own logic. The islands are substantially Christianized, and in this research, as in other published accounts I encountered, I saw no evidence of resentment over the loss of pre-colonial religious systems, so much as a concerted effort to make both systems harmonize. Interviewees readily expressed confidence that their ancestors were very religious and very serious about their faith, even if it was not the Christian faith.

People did describe practices as traditional or Catholic (or Christian) or, in non-religious contexts, traditional or Western. “Or” could be perceived as implying that these were in competition, but the primary focus of people was on harmonizing them. Interviewees said that it would be a mistake to see the practice as in competition, though certainly the relationship is negotiated. As an outsider, it was sometimes hard to perceive the boundaries, such as when the closing service for a funeral was described to me as a “traditional” event, though it was linked to a novena and Mass and included scripture passages and moral admonitions.

On Pulap, one of Chuuk’s Outer Islands, Julianna Flinn observed that people were proud to be Catholic; “they contend that Catholicism has enabled them to strengthen behavior that is valued both by the church and by Pollapese tradition. Many of the values they understand the church as promoting are consistent with what their tradition advocates, especially ttong ‘love, compassion,’ tipiyew ‘agreement,’ and kinamwmwe ‘peace, harmony.’”23

Catholicism as a liberating force?

The Chuukese context, particularly the desire to make traditional and Catholic practice harmonious, probably diminishes Catholic Christianity’s capacity to serve as a “liberating” force. Francis Hezel cites Charles Forman’s earlier observation the Pacific church is “a folk church representing the society and reflecting its standards rather than a prophetic church.”24 The same might be noted about a good many societies, of course, but the emphasis on reflecting traditional culture makes this especially likely. Further, island societies that strongly prioritize the good of the community over the rights of the individual, and that emphasize the need for harmony between traditional and religious spheres, are not likely to be fertile ground for liberationist faith. But that same observation reflects a western cultural bias about what it means to be liberating or prophetic.

None of this is to say that Catholicism (and Protestantism) has not transformed Chuukese life in enormous ways. Further, one of the ways tradition and Catholicism overlap comfortably—the way Chuuk’s culture emphasizes sharing and mutual obligation—negates much of the need for a Christian liberationist perspective to be “brought” to the culture in that regard. Chuuk already has powerful cultural norms about care for others. This can be said even as Chuukese, like other people, read the Gospel as a call to be more faithful to the values they know to be true.

As the account of family and gender roles here discusses, some habits of deference in Chuuk are quite deeply gendered, in ways that would raise questions for Western readers. Chuukese traditional culture is ruled by male chiefs, and the particular habits of deference by sisters in family contexts can seem startling.

Scholars of Chuukese culture are quick to point out, though, that the reality is much more complicated. In Chuukese culture, family structures are traditionally matrilineal. Male chiefs govern, but they are chosen by the women, and land is owned collectively within women’s family lineage—passed down from mothers to daughters, rather than fathers to sons.25 Women own the land, the most precious resource, and have veto power over its appropriation. Women don’t speak in traditional settings, but do have opportunities to make their voices heard through conversations with junior men in the system. If men ignore the needs of women, the men can be admonished, with consequence.

Sisters’ deference toward their brothers, moreover, “is a part of a larger system of respect and ranking such that everyone—male and female—defers to someone else… and the more senior a woman is, the more she is respected, attended to, and even expected to offer advice and have influence in the community.”26

Catholicism brought some kinds of restraints that did not exist before. “Catholicism has brought ideological pressure against premarital and extramarital sexual affairs, and consequently some embarrassment ensues when a young unmarried woman becomes pregnant.”27 It also added language about obedience to husbands.28 Divorce is harder after Catholicism took root—the bond between spouses used to be very easily breakable—but women would still not be expected to stay in an abusive relationship.29

Flinn suggests that Westernization, not merely Christianity, has resulted in women being pushed out of productive roles into household ones (cf. Hezel’s argument about how the rise of the nuclear family household complexifies family life in Micronesia).30 She writes, “Oddly enough, it is Catholicism… —not American democracy—that to Pollapese preached that the voices of women, the ‘words’ or ‘speech’ of women, should be heard."31 Women don’t lead services, except Rosaries at funerals, but do participate in parish council and parish management. These opportunities are not only managerial, but oratorical, in a society that believes in the power of words to change situations. "Pollapese explain that Catholicism insisted that, since women have knowledge and experience, these should be expressed, heard, listened to, followed.”32 This power has not transferred over into a right for women to speak at traditional gatherings, or really to be heard in government matters in Pulap, but it is real in church settings.

Many of the factors that empower women in Chuuk are perhaps more closely related to opportunities to speak, more than to distinctively religious concepts, but two elements of the content of Catholicism stand out. Notably, Flinn finds, women imagine Mary as “an active foe of Satan rather than a passive handmaiden.”33 She also explored a variety of ways that the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, as celebrated by the women there, “celebrates womanhood on Pollap and asserts that women play essential roles in production and other aspects of community life.”34

- 1Particular thanks is due to Francis X. Hezel, S.J., author and long-time steward of the Micronesia Seminar. His writing is a foundation for the entries that appear for Micronesia on this site. He enabled many of the contacts that led to interviews and site visits. On Guam and in Chuuk, it was remarkable to witness how many people valued his scholarship on Micronesia, and were grateful for his work for decades as a teacher and a minister. Thanks as well to Frs. Fernando Titus, Kaster Sisam, Arthur Leger, S.J., and then bishop-elect Julio Angkel for their kind hospitality and insights. The entries here are based on 12 interviews and many more informal conversations at sites in Chuuk and Guam, and the written sources cited.

- 2In the 1973 census, the proportion of Catholics and Protestants (Congregationalists plus other Protestant denominations) was almost exactly even, at just over 49% each. In 2000, 51.5% identified as Catholic and 44% as Congregationalist/Protestant. Weno and Fono were 44 and 39% Catholic in the 2000 Census. Chuuk Branch Statistics Office, Division of Statistics, Chuuk State Census Report: 2000 FSM Census of Population and Housing 2002, 58-59; Data from the 2010 census are taken as summarized on charts at http://pacificweb.org/fsm-chuuk/.

- 3Ward Goodenough, Under Heaven's Brow: Pre-Christian Religious Tradition in Chuuk (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 2002), 26.

- 4Jay D. Dobbin, Summoning the Powers Beyond: Traditional Religions in Micronesia (Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press, 2011), 22, 208. On the region’s pre-colonial history, see Francis X. Hezel, The First Taint of Civilization: A History of the Caroline and Marshall Islands in Pre-Colonial Days, 1521– 1885 (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 1983). For a brief history of the pre-colonial history of the Micronesian peoples, see Glenn Petersen, Traditional Micronesian Societies: Adaptation, Integration, and Political Organization in the Central Pacific (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, 2009), 37-65.

- 5Dobbin, Summoning, 22.

- 6Goodenough, Under Heaven's Brow, 91-105, 123-133.

- 7Goodenough, Under Heaven's Brow, 87-88.

- 8Dobbin, Summoning, 208.

- 9The comments cited were from American missionaries and traders, who were the first Westerners to try to settle in Chuuk. Francis X. Hezel, S.J., Strangers in their Own Land: A Century of Colonial Rule in the Caroline and Marshall Islands (Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 1995), 63.

- 10Hezel, Strangers, 98, 100.

- 11Francis X. Hezel, S.J., The Catholic Church in Micronesia (Pohnpei, FSM: Micronesian Seminar, 2003), 115-130. The chapter on Chuuk is also accessible online at http://www.micsem.org/pubs/books/catholic/chuuk/index.htm.

- 12Hezel, The Catholic Church in Micronesia, 133, 137.

- 13Juliana Flinn, “Catholicism and Pulapese Identity” in Christianity in Oceania: Ethnographic Perspectives (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1990), 224.

- 14Goodenough, Under Heaven's Brow, xvi.

- 15Goodenough, Under Heaven's Brow, xvii. While Goodenough suggested that much more work needed to be done on the relationship between contemporary Christianity and pre-Christian religion, his book emphasized practices that by that time had disappeared from the culture. “Readers should understand that there is a vast difference between then and now.” (xviii).

- 16Flinn, “Catholicism and Pulapese Identity,” 225.

- 17For an excellent overall summary, applied to Micronesia more broadly but based on long experience in Chuuk and Pohnpei, see Francis X. Hezel, S.J., Making Sense of Micronesia: the Logic of Pacific Island Culture (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i, 2013), especially chapters 2, 3, and 7.

- 18Hezel, Making Sense of Micronesia, chapter 4.

- 19Chamorro culture certainly emphasizes respect and deference for family, but the degree of freedom, independence, and ability for self-expression in Guam is notably different.

- 20Juliana Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro: Catholicism and Women's Work in a Micronesian Society (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2010), 84. Flinn had Pulap in mind when she wrote this, but the same is true for all of Micronesia.

- 21Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 95. What she wrote here about individuals in Pulap similarly seems to apply to the interrelationship of the three realms in all of Chuuk.

- 22Commerce is another realm that one might expect to see added to this list, but in most ways observable to me, commerce was still largely governed by traditional and government norms.

- 23Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 113.

- 24Charles Forman, The Island Churches of the South Pacific: Emergence in the Twentieth Century (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1982), 103.

- 25Matrilineal inheritance is somewhat typical in all of Micronesia, but is not part of every island’s traditional culture. Yap is among the exceptions. Where it is traditional, such as Chuuk, the system is still largely intact today, though it is weakened in places like Weno, the capital, where some families have moved to find work in town, and build houses on their own small lots.

- 26Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 95.

- 27Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 129.

- 28Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 128. Only in contexts of discussion about Catholicism did Flinn hear talk of obligations to husbands.

- 29Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 95.

- 30Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 167.

- 31Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 132.

- 32Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 132.

- 33Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 20.

- 34Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 20.