On the islands of the Chuuk Lagoon, interviewees reported that the Rosary and devotion to the Virgin were important in their lives, both in communal gatherings and at home. Few spoke much about the power of the saints, even when prompted, except to note that the saints after whom some parishes were named were celebrated on parish anniversary days or the saints’ feast days.

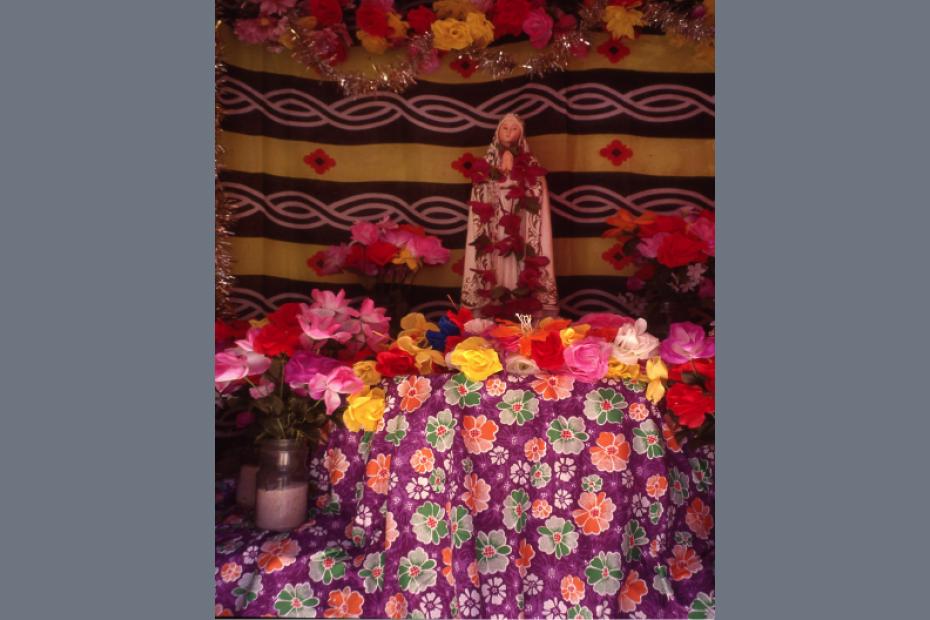

Juliana Flinn, who has conducted research on the island of Pollap (Pulap), an undeveloped, subsistence community on an Outer Island of Chuuk state, about 230 km west of the Chuuk atoll, has written extensively on how influential Mary is to believers there. There are more images of Mary than anyone else in homes in Pollap. The village has a special, well tended Fatima Shrine on the edge of the settlement, with devotions that take place there.1 Rosaries are a well-attended form of daily prayer at church (where there is no resident priest). Every Saturday, an image of Mary is carried from one house to another, with prayers taking place at each home.2 December 8, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, is a major feast of the year, and May and October are marked for Mary as well.3

Perhaps even more interesting than the fact that she is so highly esteemed in Pollap, is the set of ideals that Mary represents there. “First and foremost, she is the Mother of God and the ultimate nurturer, and as such, she protects Pollapese from storms, nourishes their taro [a food source], provides guidance for families, listens to and helps with their personal problems. Mary serves as a model for women on Pollap, yet hers is not a model of simple meekness or passivity: Mary is also the woman who has trod on the head of the devil—clearly a potent, active deed.”4 Having listened extensively to the ways people discussed Mary, Flinn notes, “The Pollapese celebrate the strength of Mary’s motherhood, not her virginity, nonsexuality, or domesticity.”5 Her virginity is not ignored or discounted, but for Pollapese, Mary is “a provider, a mother, and an enemy of Satan.”6

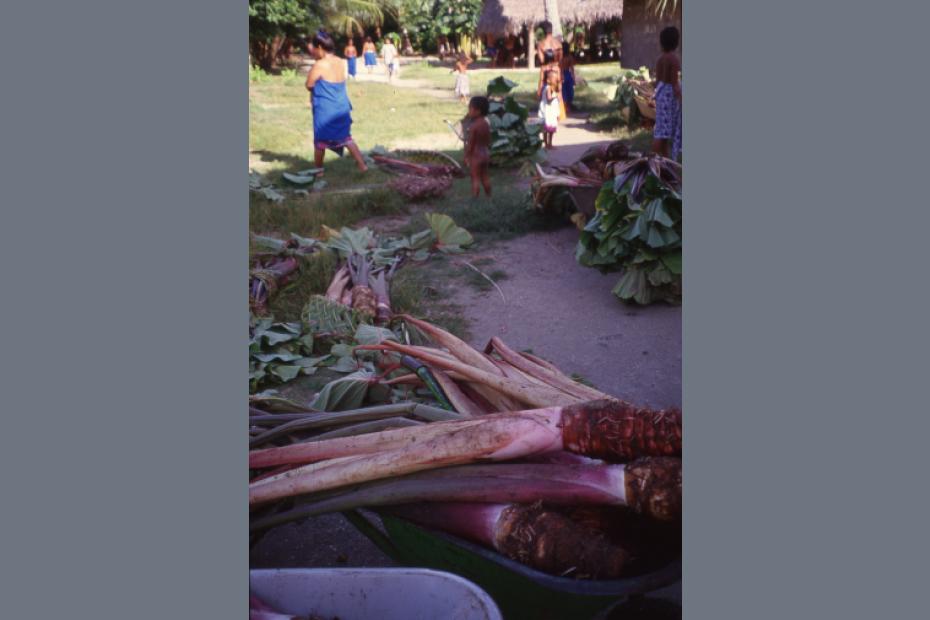

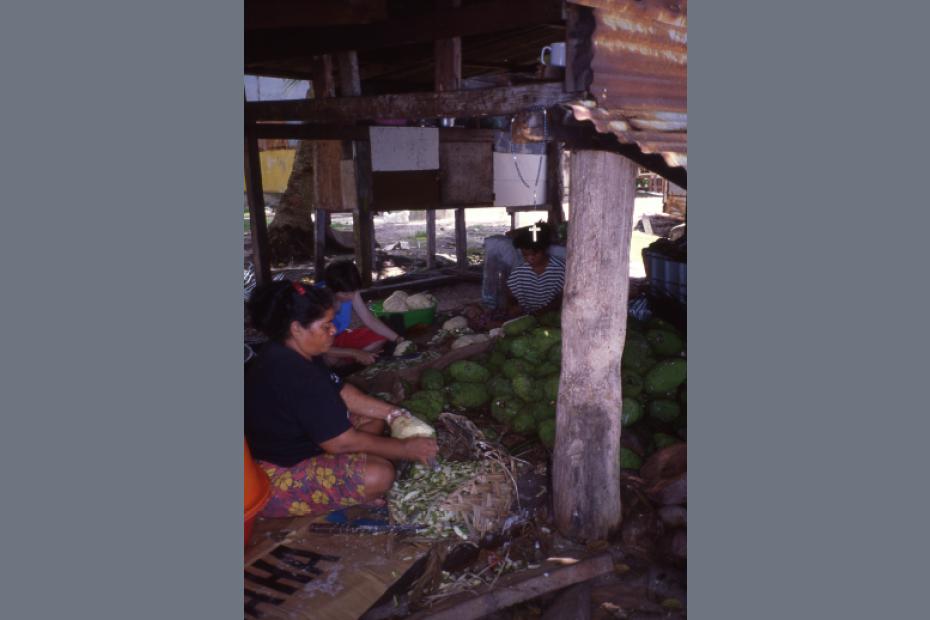

These understandings of Mary reflect the Pollapese framework of what it means to be a woman, which entails being strong, capable and responsible. “Pollapese mothers are not idealized as staying in the home and devoting themselves to children—at least not in the traditional Western sense. The image is certainly not that of a housewife, freed from outside work and devoted solely to care of a house and children. In fact, in order to care for children, women on Pollap must cultivate the staple foods and produce essential material goods. A mother is a provider, a breadwinner, a producer of goods, not a housewife.” 7 Men fish and have other responsibilities, but women on Pollap are responsible for the difficult task of raising taro, a key food staple.8 In fact, when asked to list the responsibilities of women, women mentioned taro farming first and foremost before they mentioned child rearing, cooking or cleaning.9

Mary is not only a model for women in Pollap, according to Flinn. Among the key qualities she is admired for is “showing patience (liklltiw), especially in the presence of suffering, which is a type of strength in the face of adversity. Mary is not presented as a woman who happens to be at the whims and mercies of other people and meekly accepting of what happens for lack of any other options. Nor does she resort to tears of hysterics. In much the same way that chiefly people are expected to remain quiet, calm, and patient in the face of complaints and problems, Mary exhibited patience in bearing the problems of her life.”10 This, in Pollapese society, is not only the mark of a strong woman, but a strong person. Women on Pollap, like other Micronesian women and men, are expected to demonstrate humility, patience and deference, to restrain themselves from showing anger. “If Mary ever felt anger, she would not let it show,” one woman explained.11

Feast of the Immaculate Conception

Women do take the lead in celebrating Mary in Pollap. One of the most intriguing manifestations of that responsibility is the December 8 Feast of the Immaculate Conception. A major event for Pollapese Catholics, it is one of the four major Catholic feasts of the year there. Women put extraordinary effort into making the day a success.12 Flinn describes how the feast is celebrated with food offerings of taro, a sometimes human-sized plant. The offerings symbolize a commitment to honoring Mary with the fruit of hard labor. The day includes competitive celebrations of who has grown the largest taro, along with songs and skits, even as it provides an opportunity to honor Mary and contemplate their own spiritual state, and is celebrated with a Mass and a Rosary. Inside the church, Flinn reports the celebration is serious, energetic and vigorous. Outside, it was often an occasion for singing, dancing, teasing and letting loose, and a time to celebrate women’s strength by celebrating by and with their most successful products.13 The skits of the day reinforced the values of Pollapese culture, of humility over arrogance.

Watch Juliana Flinn's lecture on "Mary in Micronesia: Breadwinner, Protector, and Strong Role Model for Women" below.

- 1Juliana Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro: Catholicism and Women's Work in a Micronesian Society (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2010), 141.

- 2Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 142-3. The ritual apparently owes its origin to Filipinos whom Pollapese people met on Weno, and the statue was even a gift from them, on the condition that they carry out the ritual.

- 3Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 148.

- 4Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 141. The act of crushing the devil’s head, an interpretation of Genesis 3:15, is the first reading at Masses on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. Catholic tradition regards Mary as a second Eve.

- 5Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 164.

- 6Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 19.

- 7Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 34.

- 8Flinn notes, “Although people do acknowledge that men sometimes work in the gardens, culturally it is entirely at men’s discretion to do so… cultivating taro remains essentially a women’s job. Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 67.

- 9Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 66.

- 10Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 142.

- 11Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 158.

- 12Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 15-19.

- 13Flinn, Mary, the Devil, and Taro, 24-30.