Animitas, roadside shrines to the dead, line the roads from desert north to the rainy south of Chile, numbering in the tens of thousands, especially along rural highways and in poor and working-class areas of small cities and towns.

Small shrines with Catholic symbolism are found in other parts of Latin America as well—in El Salvador, simple crosses mark spots where traffic deaths occurred, and in neighboring Argentina roadside shrines to legendary, unofficial saints Gauchito Gil and Difunta Correia are common along the roadside. Still, Chilean animitas stand out in a number of ways.

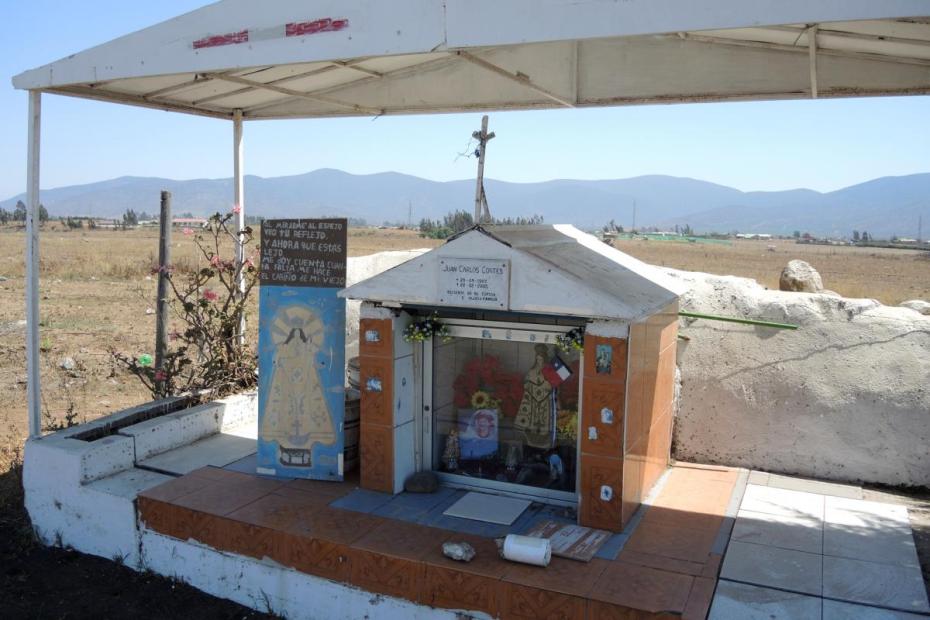

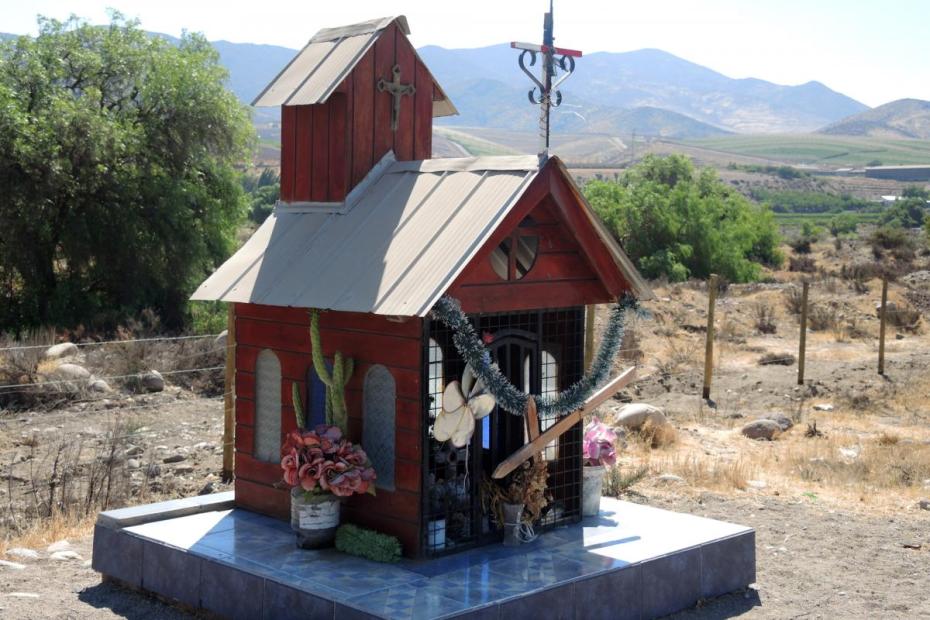

In Chile, an animita marks a place of tragic and untimely death, “mala muerte,” memorializing people who were taken suddenly, in some way perceived as unjust—today mostly as victims of auto accidents or killings.1 But animitas appear to do more than just memorialize, “personalize public space for personal memory purposes,” provide a means of aiding the bereavement process and “sensitize[e] others to the suffering and loss of a loved one.”2

The term animita, which is applied to roadside shrines only in Chile, identifies one important difference from the other shrines linked above. The word refers not only to the shrine, but to the soul of the dead housed there.3 Animitas are not simply memorial markers, but serve as homes for the souls of the departed. They are places where the living can visit and seek intercession from those souls, the suddenness of whose death gives those deceased special spiritual power. Bodies are not buried there. Instead, the animitas mark the spot where body and soul were separated, and where the soul may linger and still be reached, at least for a while, by the living.

Animitas are not sanctioned by the Church, nor is the theology behind them, but they are generally set up by Catholics and make use of Catholic symbols. Students of the phenomenon make clear that these are not “dissident” practices, but rather entail a penchant for finding sources of grace and intervention among the people.4 Given their ubiquity, and their association with tragic, life-denying events, many Chileans likely encounter Catholic symbols at animitas more frequently, and in a more vivid context, than anywhere else.

The history and origin of the shrines is debated, but references to them date to the 19th century.5 A few of the most popular animitas still in use, like Santiago’s large Raimundito shrine, date from 1900-1960.6 Their number and visibility is said to have grown in recent decades.7

Some animitas-like shrines are visually secular, but most make use of religious symbols, or combine sacred and secular elements (a statue of the Our Lady of Mount Carmel might be next to a young man’s football trophies). Typically, they are shaped like a house or church, but can also be grottos, monuments or flat walls.8 They are created by and for poor people, and are very much works in progress. Many have fresh flowers and candles burning years after they are set up. A small number even have ex-voto plaques like those at larger Marian and saints’ shrines, thanking the deceased “for favors conceded.” Other animitas are in poor repair or abandoned, not simply because they have been forgotten, but because the animita, the soul, is deemed to have left this world, something that visitors can know because the animita has ceased to be of help to the living.9

The relationship to the dead represented at animitas is one of affection and empathy more than fear. Nakashima Degarrod reports, “When asked about the reasons for them to venerate and trust the souls, most people respond that they are like them. The souls belonged to people who led similar lives, who were marred by flaws and who suffered and experienced equivalent problems, unlike the official saints who led perfect moral lives, and thus they can better understand and help the living.”10

- 1Orestes Plath, L’Animita: Hagiografia Folklorica (Chile: Unlimited, 2009), 1.

- 2Isidora Urrutia Steinert and Eduardo Valenzuela Carvallo, “Religiosity at the Roadside: Memorials, Animitas, and Shrines on a Chilean Highway” Journal of Contemporary Religion 34, no. 3 (2019): 447, 449.

- 3Lydia Nakashima Degarrod, “Souls of Virgins, Victims and Bandits: Searching for Miracles and Justice in the Chilean Roadsides and Streets,” in Roadside Memorials: A Multidisciplinary Approach, ed. Jennifer Clark (Armidale, N.S.W.: Emu Press, 2007), 140.

- 4Steinert and Carvallo, “Religiosity at the Roadside,” 464.

- 5Nakashima Degarrod provides an excellent English language summary of those arguments, “Souls of Virgins, Victims and Bandits,” 140-147.

- 6The folklore behind many of these is recounted in Plath, L’Animita: Hagiografia Folklorica.

- 7Steinert and Carvallo, “Religiosity at the Roadside,”450.

- 8Steinert and Carvallo, in their own in-depth description and categorization of shrines along one highway, suggest that some of the types of sites described here, such as the secular ones, are better categorized as memorials or shrines, but they still categorized 80-85% of the roadside shrines they found as animitas. They also admitted that the distinction is seldom clear cut. “Religiosity at the Roadside,” 450-458.

- 9Degarrod, “Souls of Virgins, Victims and Bandits,” 148.

- 10Degarrod, “Souls of Virgins, Victims and Bandits,” 149.