Bailes religiosos, religious dances regarded as a form of prayer — even an ideal form of prayer — are an essential part of the faith life of many Catholics in northern Chile, as they are in parts of Bolivia and southern Peru. Hundreds of bailes — the confraternities of dancers and their supporters, formally titled as “religious societies” — are organized in cities like Arica, Iquique, and Antofagasta.1 Each baile is organized to dance at any one of a variety of religious feasts throughout the year, but the largest of the gatherings takes place each July in La Tirana, a town built around a shrine church in the Atacama desert, one of the driest deserts in the world.

Normally a town of fewer than 1,000 people, La Tirana fills with more than 200,000 people during the feast, which centers on the feast day of the Virgen del Carmen (July 16), but lasts from July 10-19.2 Thousands of pilgrim dancers, members of 197 different bailes, fill the church, the plaza, and the surrounding streets. Busloads of other pilgrims come in to visit for a day. Situated before statues of the Virgen del Carmen, dressed in colorful costumes, and often accompanied by loud drum and brass bands, the bailes take turns dancing from morning until late at night, stopping only when Mass is taking place in the sanctuary. When they fill the square, the sounds of competing bands can be overwhelming.

Bailes, or dance groups, have 20 minutes allotted for entry and farewell dances before the Virgin inside a sanctuary. These dances take place 24 hours a day, except during scheduled Masses, and take many days to complete.

The bailes are a distinctively northern cultural phenomenon, puzzling to Catholics from of other parts of Chile. One dancer reported that when her group was invited to dance at an ordination in Santiago, “it was shocking to the people there.” The dances have their roots in pre-Christian and Spanish traditions, but in a number of startling ways are products of the 20th century, even, quite remarkably and explicitly, of Hollywood films. Bailes members who dance at La Tirana fundraise and pay dues year-round, and practice from March onwards to prepare for the feast. All the dancers are, as one leader described it, “from the bottom half of society,” but they sacrifice and save all year long to bear the cost of travel, costumes, accommodations, and hiring a band to accompany them.

Highly organized and lay-led, the bailes are structured in local associations under the wing of a federation that cooperates with local clergy, the bishop, and civic authorities to bring the feast to life. A lay-led federation and 11 local associations approve the dances, music and costumes, set norms for discipline, and make it possible to organize such a huge event annually.

In La Tirana, each baile shares housing in its own building or camping area, eats in common, and dances in costume before the Virgin a number of times in the sanctuary and in the streets. On the eve and night of July 16 they stay up all night celebrating the arrival of the feast, which is marked by fireworks at midnight and is followed by celebrations with dancing and food.

‘This is not folklore’

The northern region of Chile has a rich tradition of folkloric dance. Many of La Tirana’s dancers, and all of the bands, are also engaged in folkloric dancing. To an outsider, it is often difficult to discern the difference between folkloric and religious dance on the basis of costumes, dance steps or music. Even baile and association leaders could not give examples of how to recognize the difference.3 But they and the dancers were always at pains to say that the dancing at La Tirana is radically different. What matters is that the dancers, and their costumes, are dedicated to the Virgin, and are using the dance as a form of prayer to her. That interior perspective, they say, changes everything. The dancing involved is always ritualized, not simply improvisational or individualized. It seldom entails dancers touching.

The presence of the Virgin, in the form of the statues in the church and at the baile’s compound and dances, is also a marker of the distinction. Her image is taken as a genuine stand-in for her, and can evoke evident, deep emotion in dancers, especially when they come before the large image in the sanctuary. Visiting and dancing before the large image of the Virgin in the sanctuary is a primary objective of the groups. Each group dances a formal, 20-minute “entry” and “farewell” before her. These are consistently described by interviewees as the most moving moments of the feast for the dancers, when they pour out all the hopes and challenges that brought them there, or say goodbye and wonder if they will be able to return again. When dancing in the streets or visiting each others’ dormitory compounds, bailes also always dance in front of an image of the Virgen del Carmen, carried or rolled on a platform. Observers in the plaza and streets know that they should never stand or walk between the dancers and their image of the Virgin, and that they would never applaud dancers, which would diminish the dance from prayer into performance. Dancers are generally careful not to pay attention to or perform for the crowd.4

The federation and associations work especially hard to police the boundaries that assure that this does not become a secular feast like Carnival, or even a folkloric event. The musicians who accompany the dancers at La Tirana are largely members of folkloric bands who work for hire, but the dancers cannot mix the forms. Several years ago, one baile lost its right to dance at La Tirana because images of them dancing in their trajes (the costumes designated only for sacred dance at La Tirana) at a folklore festival showed up on Facebook. Makeup on dancers is discouraged or kept to a minimum, since that would make it more like Carnival, and the federation succeeded, with help from the bishop, in preventing alcohol sales in La Tirana during the feast to prevent Carnival-like drunkenness. The appearance of a dancer intoxicated is cause for expulsion for him and sanction for that baile.

Putting on a traje

One of the most important symbols of the sacredness of the bailes to the dancers — though simultaneously often the greatest source of disjuncture for outsiders — is the traje, the costume worn for dances. Ironically, most traje bear no traditional Christian symbols, and often reference traditionally non-Christian groups, rather than biblical church-historical figures. Yet the dancers speak over and over again about the powerful symbolism of putting on, and taking off, a traje. “Costume” might suggest a merely theatrical quality, but every dancer interviewed insisted that this clothing was sacred, and said that they felt entirely different when in it. One interviewee drew this parallel: “When we put on our trajes, we feel that it’s the same as when a priest puts on his vestments.”

Some traditional trajes on display in La Tirana.

Trajes must be made specifically for sacred dance — a folklore dance costume used for the sacred dances is unacceptable — and once used for the sacred dance it cannot be worn for other purposes. A new dancer’s traje always needs to be blessed before it is worn. Trajes often include hats, which are otherwise forbidden in the sanctuary. Diablada, or devil’s dance trajes include masks, but these cannot be worn in the sanctuary. A new dance group cannot use the same traje as a previously incorporated one. When wearing the traje, a dancer cannot eat, drink (except water, if necessary), smoke, buy things, take a selfie, or use a mobile phone.5 Many dancers, interviewees said, even ask to be buried in their trajes.

Racial and ethnic appropriation plays a remarkable role in the choice of trajes. Notably, with exceptions that were defined by dancers themselves in interviews as “Bolivian” or “Peruvian,” most mimic ethnic identities different than their own, though they are often ethnic statuses that were described as belonging to people who, like the dancers themselves, were somehow subordinate peoples in the global scheme of things.

The major categories for bailes and trajes include:

The Baile Chino, the oldest incorporated dance group at La Tirana, incorporated in 1908 in Iquique, wears brown jumpsuits and white capes, and dances to wood and reed pipes — not brass bands — by hopping from one leg to another. Its dance stands out as not particularly rhythmic. Interviewees at La Tirana claimed that it had come from the Chinese who traded and settled in the region, but scholars tend to ascribe its origins to Andacollo, a mining city 1300 km south, and sometimes to say that the word Chino signifies a servant role, not ethnicity.6

Bailes Morenos, perhaps best translated as “brown-complexioned” dancers, wear silken, blousy pants and shirts, and a silken crown-like hat. Their dances, according to the interviewees, derive from the population of African slaves who were brought to the region. The movement of their feet is said to mimic slaves dragging chains.7 Jumping Morenos, dressed similarly, jump, as one might expect, but describe themselves as doing so with chains at their feet. Morenos Rusos, “brown (or swarthy) Russians,” carry similar names but have Cossack-like costumes and a different dance.

Sociedad Religiosa Morenos Sara del Carmen

Bailes Chunchos, whose dress and dance derive from warriors of the Peruvian jungle, wear a blouse and skirt trimmed with brightly multicolored feathers, and tall headdresses and capes made from the same feathers. Their dance is more vibrant than the Morenos or Chinos.

Bailes Pieles Rojas — literally, “redskins” — are a startling sight at La Tirana, since they involve Chilean people, most of indigenous or mixed origin themselves, appropriating the costume of North American Sioux, Cheyenne, Apaches, Dakota, and other tribes. Many dance around fires, except in church.

Diabladas, devil’s dances, often draw a disproportionate amount of attention because of their costumes and the wildness of their spectacle. At La Tirana there are officially recognized diabladas — confraternities of dancers in devils’ costumes — and diablos sueltos, “loose devils,” who do not belong to any formal group, but come to the feast and join in on other groups’ dances if allowed. Devils’ dances came to La Tirana through Bolivia, but were originally imported there by colonial-era Spaniards, who used them to “express the struggle between good and evil, characterized by the Archangel Michael and the devils.”8

A "diablada" or dancing devils baile, the "Servants of the Virgin" from the city of Iquique

Gitanos — gypsies or Roma — dance in silken gypsy costumes, waving handkerchiefs. They are allowed to wear a bit more individualized jewelry to express themselves “as gypsies would.” A subgroup of the gitanos is the Gitanos Espanoles, or Spanish gypsies.

The Bailes Osadas are a fairly new group. The Osadas from Arica dance in furry polar bear costumes (oso means “bear”), without masks, wearing patriotic-colored sashes with the words “united for the faith” on the banners.

Members of the Osadas (bear dancers) Servants of God from Arica

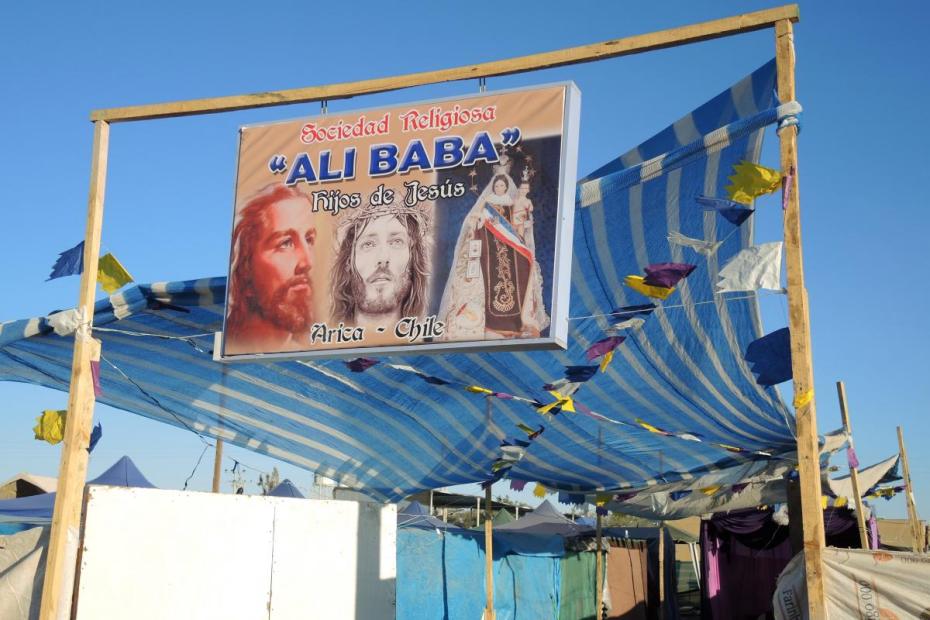

Other groups include Hindus, Arabs and “Ali-Baba” bailes, in silk and turbans; and dances that draw from elsewhere in South America, like Kayahuallas, Sambos, Thukkuri, Cullaguas, and Llameros (Llama-herders).

Readers from many outside cultures will surely find the costumes odd for a Catholic event, but dancers there simply see them as logical and an important part of their own identity. Dancers volunteered that they had encountered instances where outsiders saw their appropriation of other ethnicities’ costumes problematic. A Sioux group reported that a visiting North American Sioux delegation was at first deeply discomfited, but “came to understand that what we are doing is sacred.” In a number of ways, the history of the feast reveals that the choice of these trajes is a story of mestizo peoples cut off from their own cultures of origin, adopting other “comparable” identities over the course of this century.

The music of the bailes varies. Loud brass and drum bands, competing with one another in the plaza, have become the norm. The baile Chino, however, still uses wooden flutes. Morenos, and some other groups, carry and rely on matracas, wooden grinder-like instruments that help them keep time and (for Morenos) mimic the sound of the chains as they step. Gitanos use tambourines, but usually in coordination with a band.

Wearing a traje is one of three powerful ways that clothing plays a ritual role at La Tirana. The clothing that the Virgin wears takes on powerful symbolism throughout the feast as a mantle of protection. Pilgrims wait hours in line to visit her statue. While some touch her feet, many more people, with the assistance of volunteer lay “sentinels” who stand with her, rub unlit candles, statues, rosaries, engagement rings and other objects — and quite often children — up against her clothes as a way of having them blessed. When her statue descends from the front balcony of the church at a high point on her feast, rolls of colorful ribbon more than 100 meters long are thrown out into the crowd and held onto as an extension of her cloak.

In most bailes, the Christ Child who is carried in the arms of the Virgen del Carmen statue is clothed in the traje of the baile. Some said that this is a way of inviting the child Jesus to be part of the dance. Another said, “During the dances, in our hearts, we try to show that he is of us. We show our closeness.” Another said it shows that “the people of the baile are in her arms like Jesus.”

At the goodbye dance in the sanctuary, the dancers who have completed their manda and who thus will not dance again, take off their traje, or at least part of it. As one anthropologist notes, “with this gesture, the dancer returns outside the communion of the group and is free of all obligation to the baile…. The traje is a symbol, strong and sensible, of personal membership and special protection from the Virgin.”9

Sacred time in a sacred place

Scholars of religion like to talk about themes like embodiment, performance, sacred space, and sacred time. It is startling at La Tirana how often these themes were raised by interviewees. On embodiment, one girl, 12 years old, summed it up this way: “When I pray with words, it is important, but this allows me to put my whole body into the prayer. It shows her [the Virgin] that I mean what I pray and that I’m dedicated to her.”

While the sacred geography of La Tirana is discussed more extensively here, and the order of events here, it is also clear that the feast marks the cycles of life for a huge number of participants, the majority of whom experience it as an annual event for many years. Many wait to have children baptized or receive first communion there. Some are married there, and even buried there. The bailes and associations spend much of the year planning and fundraising for the feast, and dedicate winter vacations to it (July is winter in Chile). Many comment that the nighttime celebration on the eve and morning of the Virgin of Carmen’s feast day is their New Year’s Eve, the night that divides one year from another, despite what the official calendar says. On that night, “the happiness is so large that, living this, you just get emotional. This is the meeting point of human life and sacredness.”

The great majority of dancers describe themselves as pampinos, descendants of the people of this region. Returning to the sanctuary takes them back to a home of their ancestors, but also in a powerful way to a home of the Virgin. As shared owners of compounds or camps there, they live, at least for a short time in the sacred space, and by setting up statues of the Virgin at the heart of their compounds, mark these as sacred spaces.

The Virgin, Jesus and loose devils

The feast at La Tirana is clearly centered on the Virgin, more than on Jesus or the Father. Marian-centered devotion has deep affinities with pre-Columbian devotions to the Pachamama, an Andean female goddess. Unlike at least one other Andean Catholic feast, it is also centered exclusively on the Virgin of Carmen, rather than on any of her other manifestations.10 Asked about the qualities of the Virgin that were most salient to them, she was repeatedly associated with kindness and benevolence, an interesting juxtaposition in a place called La Tirana, “the tyrant.” One woman said of her presence in the statue in her compound, “She is the image that carries all of our laughter, all of our tears, all of our struggles.”

Clergy have worked for a century, notably since the institution of the asesores, to tilt the balance in a more christocentric way, but acknowledge that there are still tensions. The dancers, for example, want more time to dance, and resist the priests’ attempts to add Masses to the schedule if that cuts into dance time. The Eucharistic chapel in the temple has few visitors inside when the line to see the Virgin stretches for blocks. The system of awarding points to dance groups that attend Masses and retreats suggests that at least for some dancers, or to some degree, one kind of religious practice is much more valued than another. In the dances in church, and in the processions, the Nazareno, the image of Jesus carrying the Cross, has a distinct place of honor, but the Virgin receives the most attention. Within their lifetimes, older interviewees remembered that before they were accepted in the church, “we weren’t really well-formed religiously” having been left on their own. Still, at least some distinctions of catechesis may be lost on some dancers: one leader reported that the asesores had since taught them not to refer to the Virgin as divine, and to remove all such references in their songs, “and other little things like that.”

A Mass is held for the leaders from the Asociación Virgen de la Tirana of Arica. Bishop Moises Atisha Contreras is the celebrant.

None of this is to suggest that there were open forms of conflict, but rather that there is some negotiation always in progress. A small number of interviewees made clear that the dances were, as they wanted them to be, the only forms of contact they had with the church. Far more often, interviewees seemed very happy with the degree of support and respect they received from the clergy, and saw the context of their work very much within the realm of the Church. Many clergy, too, were deeply committed to the flourishing of the bailes, and dozens attended during the week. The theme of respect surfaced repeatedly when interviewees spoke with satisfaction about the difference between now and the past, particularly in regard to the church in Arica. A majority also clearly and in repeated ways described it as their responsibility, through their associations, to assure the Christian focus of the celebration.

Beyond this juxtaposition, one element that might prove most startling to readers from many parts of the world is the presence of devils among the dancers, whether as diablos sueltos, loose devils who dance into and out of the organized bailes’ dances in the plaza, or even more so as diabladas, organized Christian confraternities who dance in devils’ costumes.

Loose devils are present in images from the dances from before the 1940s, and evidently were accepted by the people. The first diablada confraternities were organized by the late 1950s.11

Interviewees’ attitudes toward loose devils, and toward devil costumes themselves, offer an intriguing window into the feast. Most attitudes ranged from seeing their presence as unremarkable to even seeing it as obviously reasonable. The latter said this because they showed that “even the devils have to bow before the Virgin.” Indeed, devils’ dances were always supposed to conclude with a bow before the Virgin, a legacy of the devils’ dance morality plays imported by Spanish colonists centuries earlier. A few worried not about the devils’ personas and costumes, but the fact that their dance style crossed a boundary towards being too carnivalesque.

But one dancer's comments said a great deal. The organized diablada bailes are perfectly acceptable. But the diablos sueltos? “Some of them were people who had been expelled from groups for unpaid debts and for not obeying rules. They paint their faces sometimes. They are drunk… They don’t get a formal entrada or despedida. But in 2015 they were allowed to enter into the church, because they said if they were not authorized they would go in anyway. That’s the problem. There is little discipline with them. I hear that there has been a little more self-regulation now that they receive some blessing, so they would agree to kick out someone who is drunk, or they would promise not to paint their faces.” Authentic participation is about belonging, about “becoming a member of a dance, dancing in line, paying monthly dues, sacrificing to be able to finance the whole celebration, then you come and have an entrance and goodbye, and that’s what it means to have an authentic experience.”

Another interviewee noted a tall dancer who dresses up like Ñusta Huillac, the original tirana, and comes there on her own. She is very attractive, blond and accentuates her looks with high heels, makeup, and her dress. “She calls attention to herself [rather than to the Virgin]. A little bit of blush and earrings is okay, but she is too much. If you ask her why she dances, she cannot explain it. She wants to be the center of attention. Here, the center of attention is the Virgen del Carmen. No one else. That is the problem.”

Not belonging — stepping out of the community and its rules — is a cardinal sin, far worse than dancing in the persona of a devil. It speaks to a culture confident that one finds oneself, and finds one’s way to God, particularly through membership in a community. Motivations for dancing are personal, but the act of prayer is collective, and dancers surrender some of their individuality by taking up the group identity of shared costumes and dance. When there is a problem in the group, even involving theft, the maximum penalty seems to be withdrawal of permission to dance, or expulsion of the baile from La Tirana. Exclusion is the worst punishment.

Growth beyond capacity

As the presence of so many newer baile camps in the desert outside the built town attests, the bailes religiosos have continued to expand at La Tirana. No one interviewed there thought that this was a phenomenon doomed to shrink over time, in part because they worked hard to bring it to younger generations. Young people are numerous, often even dominant in almost all of the bailes. Children are introduced into them at a very young age, and tend to grow up in it. Dancers say that some people find their way into it as young adults — as is the case where a boy meets a girl who is a dancer — but that few people join as adults.

In 1917, 10 groups danced at La Tirana. In 1985 there were 165.12 Today the number is 197, and there are as many as 30 organized bailes waiting for the opportunity to dance at the July feast. Each September these bailes gather there for an alternative opportunity to dance. A few said that some of the older bailes with less flamboyant trajes and dance steps were disadvantaged when it came to attracting young people, but everyone was clear that those groups’ traditions should be preserved.

No one worried about the future of the Church or the feast here. “This is so family rooted. My great-grandfather danced at La Tirana. My father founded this dance society. Every baby born in this family is guaranteed to grow up dancing here.” As another put it, “You can see our faith is strong, and we are many.”

Read more

P. Nelson Peña Antil, S.J., Bailes Religiosos de Arica: valoración de su historia y tradición (Chile: Procultura: 2015)

José Javier García Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile o los Danzantes de la Virgen, (Santiago: Seminario Pontificio Mayor, 1989).

Henríquez Rojas, Patricia Por que bailando?: estudio de los bailes religiosos del Norte Grande de Chile (Santiago de Chile: Printext, 1996).

- 1A baile in this context can refer to a particular dance group – the confraternity itself – or to the dance it does.

- 2Actual numbers of attendees were difficult to confirm, but 200,000 is a number that was often claimed, and that seems credible, given the number of compounds and tent camps squeezed into town with bunk beds in tight quarters.

- 3The articles on La Tirana on the Catholics & Cultures site are based on observation at the feast of La Tirana and interviews with members of 18 bailes from July 13-19, 2016. While videos and images on the site cover the dancers from all over northern Chile, the interviews were all with bailes from the city of Arica, members of both the Asociación San José de Arica and the Asociación Virgen de la Tirana. Together those associations represent the 40 bailes from Arica that came to La Tirana in 2016. Special thanks to Rev. Claudio Barriga S.J., the current asesor for Arica, for considerable help arranging interviews and accommodations; to Rev. Eugenio Barber, S.J., who served for years as the asesor to the dances, who first encouraged me to look into them, and whose name still readily opens doors at the bailes; to the bailes themselves who were extraordinarily hospitable and eager to share about their way of life with audiences who might read this; and to Lauren Hammer (Holy Cross ’14), whose exceptional skill as a translator helped overcome my own shortcomings in the language.

- 4One exception, as noted below, is the diablos sueltos, or loose devils who are considered problematic in part because of their tendencies to perform. In a week at La Tirana for this research in 2016, I never heard anyone applaud for dancers.

- 5A dancer can eat in the traje during the formal visits organized between bailes, when each baile draws lots to host another baile, which dances at the host’s compound and is then feted with a meal.

- 6José Javier García Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile o los Danzantes de la Virgen, (Santiago: Seminario Pontificio Mayor, 1989) 158.

- 7On the claim of that the dances are of African origin in the region, see also P. Nelson Peña Antil, SJ, Bailes Religiosos de Arica: valoración de su historia y tradición (Chile: Procultura: 2015) 37, 44-45. Apparently 4% of the region’s population claims African ancestry today. None of the dancers interviewed in the bailes morenos claimed African ancestry. According to Rev. Eugenio Barber, S.J., Afro-Chileans are more frequently involved in dancing at another feast, Las Peñas.

- 8José Javier García Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile o los Danzantes de la Virgen, (Santiago: Seminario Pontificio Mayor, 1989) 156, 261.

- 9Jan Van Kessel, El Desierto Canta a Maria, (Santiago, Chile: Mundo, n.d.) 31-32, as cited in Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile, 248, trans T. Landy.

- 10Compare this, for example to the Feast of the Señor y Virgen del Milagro — the Lord and Virgin of the Miracle — celebrated on the other side of the Andes in Salta, Argentina, where pilgrims bring statues of a wide variety of devotions to the Virgin.

- 11Alberto Díaz Araya and Paulo Lanas Castillo, "Danza y devoción en el desierto: Obreros e indígenas en la fiesta de la Virgen del Carmen de La Tirana, Norte de Chile" (siglo XX) Latin American Music Review 2015 36:2, 155.

- 12José Javier García Arribas, Los Bailes Religiosos del Norte de Chile o los Danzantes de la Virgen, (Santiago: Seminario Pontificio Mayor, 1989) 146.