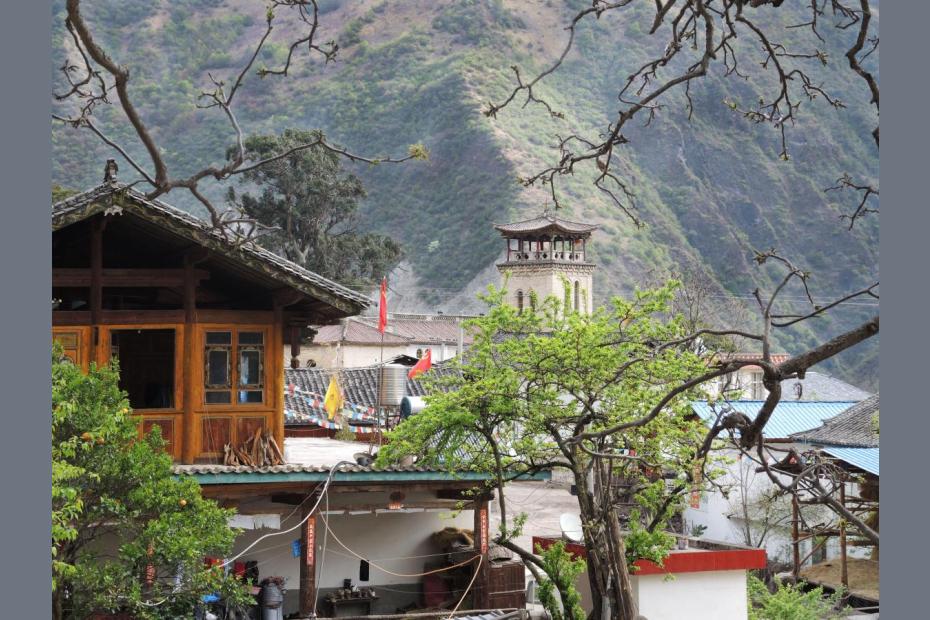

In late 19th and early 20th centuries, French missionaries established Catholic communities among ethnic Tibetan, Naxi, and Lisu peoples in a number of villages along the Lancang River in Yunnan, the southwestern-most province of China, near the borders of Tibet Autonomous Region and Myanmar (Burma).1 Situated in a sparsely populated, mountainous region along an unnavigable stretch of river far from any centers of power, the geographical remoteness of these villages is still striking today. The closest airport is an eight-hours drive through the mountains, in a small city that re-named itself “Shangri-La” to draw tourists seeking to experience that imaginary Himalayan paradise.2

Yellow-hat sect Buddhism, or Lamaism, was the dominant religion of the region when the missionaries arrived, and today, following post-Maoist reconstruction, Buddhist stupas, prayer flags and lamaseries again adorn the valley. Catholics in the villages have also worked to rebuild their Catholic churches and communities.

Almost all of the inhabitants of the Lancang River Catholic villages are Tibetan, Lisu and Naxi “minority peoples,” officially recognized ethnic groups with their own languages and cultures.3 Three neighboring villages, Cizhong (茨中) Cigu (茨古) and Niuren (纽仁), where most residents are ethnically Tibetan and Naxi, and a fourth village, Xiaoweixi (小维西), about four hours down the river, where many villagers are Lisu, provide insight into the state of Catholic life in the region today.4 Lisu are the minority people historically most receptive to Christianity, both Protestant and Catholic.5 Tibetan and Naxi cultural influences are especially visible in the design of many houses and the prayer flags above them in and around Cizhong. Putonghua (Mandarin Chinese) is the language taught in local schools, but local languages and customs play a significant role in the villages today. The local visual culture, which draws from Western, Chinese and Tibetan norms, is especially compelling.

Despite the geographic remoteness, the fate of the villagers has been reshaped repeatedly by outside influences, and is being reshaped again as the river is being harnessed by a series of dams to provide electricity to the rest of China. Some villages are being relocated to higher ground, and construction crews are building roads, tunnels and massive bridges along the river. The local prefecture is working to develop tourism to Yunnan’s Tibetan and other ethnic peoples’ sites, even including Cizhong’s old Catholic church.6 A number of villagers now own cars and vans, usually for work purposes, and young adults play on inexpensive smartphones. At the same time, buildings largely go unheated, except for a kitchen fire, and small-scale agriculture is still a part of daily life. Men often work outside their villages as drivers or construction workers, while adult women and grandparents are more likely to be at home farming and tending children.

A Cizhong cluster of churches constitutes six chapels, including Cigu and Niuren, while a Xiaoweixi cluster includes 15 chapels in three counties, some of which are not accessible by car. These are not the only churches in the broader region, by any means. In Gongshan county, between Cizhong and the Tibetan border, there are 14 chapels. This contrasts to the Tibet Autonomous Region, which has only one church in Lhasa, and where missionaries had a much harder time establishing a presence.7

Historical background

The Qing emperor, under pressure from Western powers after a series of wars, and eager to undermine the power of Tibetan lamas, allowed Catholic missionaries from France to work in ethnic Tibetan lands in Yunnan in the late 19th century. The missionaries centered their mission in Cigu village, and had some success in a number of villages along the Lancang River. Yellow-hat sect Buddhists, angry at the success of the missionaries and at the Chinese rulers, killed the missionaries and many lay Catholics, and burned the churches in 1905. The lamaseries were ultimately forced by the Emperor to pay compensation, and new missionaries from France used those funds to rebuild, re-centering their mission at Cizhong, where they built a grander church, a convent and a school.8 The missionaries organized Catholic communities along the village models they knew in France, focusing on building concentrated pockets of majority-Catholic villages, rather than ministering to scattered groups of Catholic families.9 In order to have wine for Mass, they brought viniculture to the region. By the 1930s, they were beginning to educate a native clergy for the region.10

In 1951, two years after the Communist Revolution, the last Western priest was expelled from the area, and several Catholic villagers, including the seminarians and clergy, were sent to “reeducation” camps for up to 30 years. The Cizhong church and school buildings were spared by being appropriated for a state school. Some villagers were able to go quietly to the church to pray. The Xiaoweixi church was also turned into a school, then a clinic. Some parishioners baptized and taught catechism in private.

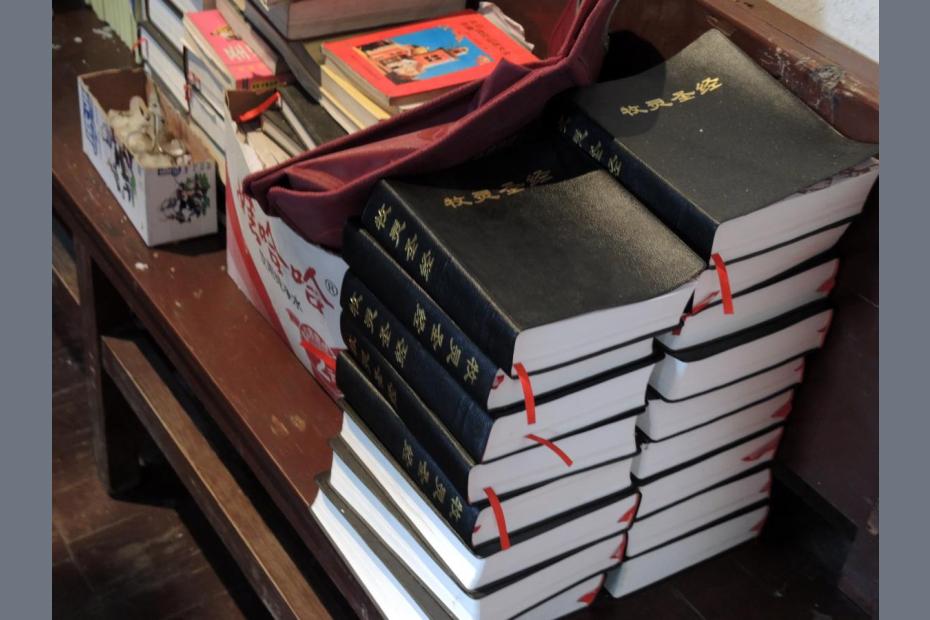

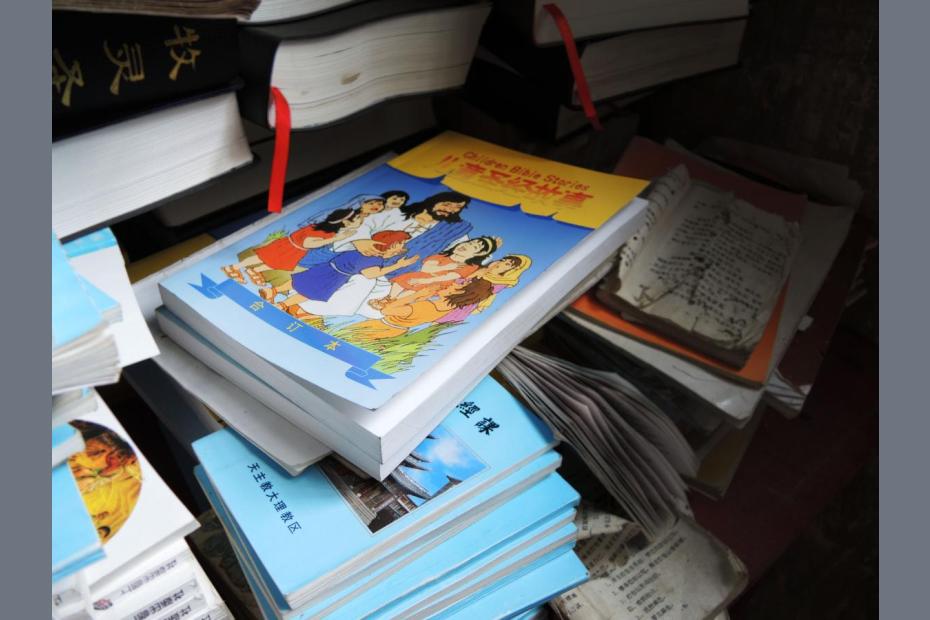

From 1966-1976, during the period of intense political upheaval known as the Cultural Revolution, both the Cizhong and Xiaoweixi churches survived, the latter being used as a storage facility. The other, smaller churches in the area were ruined. Many families prayed in private, at home, something that had to be done in absolute secret. In Xiaoweixi, most of the parishioners were illiterate, and had memorized the chants and prayers taught by the priests, and could pass on their faith that way. Only a few of the original prayer books in Tibetan survived this period.

Rebirth

After the death of Mao, under Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, imprisoned Catholics were released, and it became possible to worship again. One villager reported that after so many political campaigns under Mao, it took some time to convince many families that it was a good idea to practice in the open again.

The Cizhong church building was returned to a local church organization in 1984, and in 1997 the village primary school was moved from of the church courtyard to new quarters elsewhere. In 2006, the Cizhong church began to be promoted by the government as a cultural heritage site. In February 2008, the church was assigned its first priest in almost 60 years, Fr. Yao Fei, a Han Chinese missionary from Inner Mongolia. From its reconstitution until today, older parishioners formed living links to the missionary past. One elderly parishioner, a man who was a seminarian and was jailed for 30 years, and married after his release, is a revered figure in the Cizhong community.

The Xiaoweixi church was reopened as well, and has been administered by the county government. Shi Guangrong, who was a seminarian before 1951 and who was jailed for 20 years after the French and Swiss priests were expelled, led much of the revival, traveling up to Cigu, Niuren and Cizhong as well, and was ordained in the late 1980s. Fr. Shi’s picture is still in the chapel, and his elderly brother, who helps keep up the church, spoke proudly of his brother’s accomplishments, with the help of a priest from Sichuan, restoring the community. According to the current pastor, Fr. Tao, a local priest of Lisu ethnicity, the church was renovated in 2002 with donations from villagers, clergy and foreigners.

Cigu and Niuren churches, like a number of other small churches, were rebuilt by those villages’ lay Catholics in the 1980s and 1990s. At Niuren, one local woman claimed that the largest contributor was a local party official.

Contemporary contexts

The Niuren and Cigu churches still do not have a resident pastor, and it is not clear that they will get one any time soon. Fr. Yao said that he seldom travels out to the other churches, since he does not have a car. Catholics from Cigu and other Catholic villages in the area send a car to pick him up if there is a need for last rites or funerals. Catholics at Cigu, Niuren and these other small churches conduct their own services, singing chants that are, they say, the ones given to them by the Swiss and French missionaries.

From Xiaoweixi village, Fr. Tao, ministers to Catholics in 15 churches in three counties, traveling to three churches each Sunday, and is able to speak Tibetan, Naxi, his native Lisu, and Putonghua. All but two of the families in the village are Catholic. Fr. Tao echoed a common Chinese claim, that the higher moral standards of village Catholics prove the worth of Catholicism to Chinese society. He reported with pride that a local police official, who was not Catholic, had said that if more of the families were Catholic, he would have fewer problems in town to deal with, and none of the drug problems that now affect some other villages.

In each of the towns, pastors and locals described their communities as still being in a rebuilding mode. Political sensitivities and language barriers limited the scope of topics that could be discussed with local Catholics, and prevent us from presenting an in-depth depiction of the relationship between faith and culture in a place where minority cultures endure and are being reshaped. Each of the churches, while registered and “above-ground,” i.e. ostensibly independent of the Vatican, has some prominent image, usually of Pope Francis, that makes clear that the connection to the Universal Church is important to them.

There are no formal lay associations among the people, though the pastor said he has tried to encourage them. People work very hard, and long days, and don’t have time for that, he says. Even today, people still gather wood and twigs from the mountains for cooking, and grow many of their own foods.

Religiously, the story of the villages is the story of growth in one important sense — the number of churches restored, and the re-gathering of faith communities, but there is also some concern about the fact that the congregation is aging. In Xiaoweixi, Mr. Shi reports that Sunday Mass attendance at church is down to about 40 people a week, from its post-Mao high of 150.

Western, Chinese, Tibetan, Lisu, Naxi

The Catholic churches in the Lancang Valley exist today, as they have since their start, at the confluence of many cultures. The indigenous Tibetan, Lisu, and Naxi communities are reappropriating aspects their cultural identities at a time when the government wants to capitalize on these for ethnic tourism, even as the Chinese government is extraordinarily wary of many forms of Tibetan nationalism. But technological advances also connect them much more than before to wider cultural influences. Chinese Catholicism, including the “above ground” or official church, has adapted to Vatican II norms in liturgy, the role of the Bible, and much more.

At Cizhong and Cigu, one irony is that the legacies of the French and Swiss missionaries seem in some ways at least as influential in village life as the current pastor, who is Han Chinese and from Inner Mongolia. Fr. Yao is clearly dedicated to his parishioners and eager for help ministering to them, but culturally he too is a missionary, far from his native home. He acknowledged that in many ways he remained an outsider to them as a speaker almost exclusively of Putonghua, or Mandarin Chinese. He lamented that he had not been invited to people’s houses for ordinary visits, and only once to a wedding (weddings in local Tibetan and Naxi culture are not held in temples but at the houses of the betrothed, culminating in a banquet at the home of the groom). On the other hand, the missionaries’ influence was repeatedly apparent. Small museums at the Cizhong and Xiaoweixi churches commemorate them with photographs and written accounts. Their graves at Cigu are well tended and visited. And despite the implementation of Vatican II liturgies since the 1990s, the older chants, written by French and Swiss missionaries before 1950, are the form of worship that seems to engage churchgoers. Even the wine making that they brought has become a local agricultural hallmark.

The Xiaoweixi church is fortunate to have a priest who is Lisu, but it is influenced by outside events too, and relishes its connection to the world Church, as images of John Paul II and Pope Francis there made clear.

Beyond the fact of so many social changes from outside, the boundaries between the ethnic groups and their cultural practices are seldom fixed, simple and clear. Many families are ethnically mixed,11 and in Cizhong at least, contrary to what Madsen reports about Eastern Chinese Catholic villages, Catholics easily intermarry with Buddhists.12

As “minority peoples,” most of the local Catholics have long been allowed exemptions from the one child policy, but families still seem to have few children. In the new economy, though the villages are largely self-sufficient in terms of food production, men usually work outside village. Women are often out in the fields, gathering wood, tending crops and animals. The villages are newly prosperous to a degree that surprised urban Chinese visitors, but still do not by any means manifest a consumerist culture marked by of plethora of choices, even if they are increasingly aware of that world beyond them.

Read more

Francis Khek Gee Lim, "'Negotiating 'Foreignness', Localizing Faith: Tibetan Catholicism in the Tibet-Yunnan Borderlands." In Christianity and the State in Asia: Complicity and Conflict, edited by Francis Khek Gee Lim & Julius Bautista, 79-96. London: Routledge, 2009.

Francis Khek Gee Lim, “‘To the Peoples’: Christianity and Ethnicity in China’s Minority Areas.” In Christianity in Contemporary China: Socio-cultural Perspectives, edited by Francis Khek Gee Lim. London: Routledge, 2013.

- 1Known as the Lancang from the Tibetan Plateau through Yunnan, the river is more commonly known in the west as the Mekong. The first three villages in question are located within the Diqing Autonomous Tibetan Prefecture, a sub-province-level entity in Yunnan that borders the Tibet Autonomous Region, the geographic area typically designated as Tibet. Xiaoweixi church is in Xiaoweixi (小维西) or Tongweicun (统维村) village, Weixi Lisu Autonomous County in the Diqing Prefecture. For these distinctions, and a broader description of life in Diqing prefecture, see Ben Hillman, “China’s Many Tibets: Regional Autonomy and Local Policy in Diqing.” It is worth noting that more than half of ethnic Tibetans in China live outside the borders of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

- 2Shangri-La is the fictional location of James Hilton’s romanticized 1933 novel, Lost Horizon, about an isolated, utopic Himalayan village and Buddhist lamasery. Jiantang, the prefecture seat, was renamed Shangri-La in 2001 to draw tourists to see its lamaseries and ancient buildings.

- 3In addition to the dominant Han ethnic group that comprises more than 90 percent of all Chinese, China recognizes 55 "minority peoples." Though they interact with Han Chinese and often speak Mandarin Chinese, “minority peoples” have their own languages and customs. As is true for almost all racial and ethnic classifications, the boundaries between groups, and the criteria that link them together, are not always neat and consistent, but the designation of ethnic identity is often very meaningful. For background on the shaping of the categories of minority peoples in the regions and its relationship to Christianity, see Francis Khek Gee Lim, “‘To the Peoples’: Christianity and Ethnicity in China’s Minority Areas” in Francis Khek Gee Lim, ed., Christianity in Contemporary China: Socio-cultural Perspectives (London: Routledge, 2013). In the whole of Diqing prefecture, 33.12 percent of the population is Tibetan, 27.78 percent is Lisu, and 12.81 percent is Naxi. Population figures are from the Diqing Prefecture 2000 census, as cited in Ben Hillman, “China’s Many Tibets: Regional Autonomy and Local Policy in Diqing.”

- 4Research was conducted during Holy Week 2015, with Putonghua (Mandarin Chinese) speaking interpreters. Both political sensitivities and language barriers limited the range and scope of matters that could be discussed.

- 5Ralph R. Covell, “Christianity and China’s Minority Nationalities — Faith and Unbelief” in Stephen Uhalley, Jr. and Xiaoxin Wu, eds., China and Christianity: Burdened Past, Hopeful Future (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2001), 275-276.

- 6On these efforts in the county, including the rebranding to Shangri-La, see Ben Hillman, “Paradise under Construction: Minorities, Myths and Modernity in Northwest Yunnan.”

- 7Francis Khek Gee Lim, “‘To the Peoples,’” 111.

- 8Two dozen other churches, not visited for this project, were established, including bigger parishes in the larger towns of Deqin (Diqin) and Weixi.

- 9Richard Madsen points to this as a typical model of French missionary activity in China, in contrast to the way Protestant missionaries approached evangelization. Richard Madsen, “Chinese Christianity: Indigenization and Conflict” in Chinese Society: Change, Conflict and Resistance, ed. Elizabeth J. Perry and Mark Selden, 2nd ed., (New York and London: Routledge Curzon, 2003), 281.

- 10The historical information comes from the small museums in the Cizhong and Xiaoweixi parish compounds.

- 11Francis Khek Gee Lim, “‘To the Peoples,’” 105-108.

- 12Richard Madsen, China’s Catholics: Tragedy and Hope in an Emerging Civil Society (Berkeley: University of California, 1998), 56.