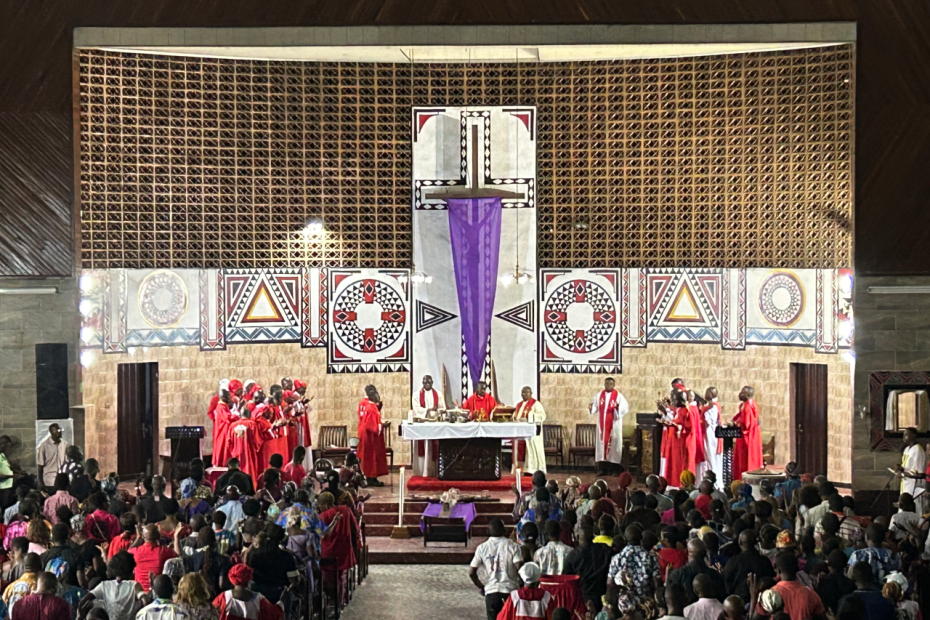

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), which covers a central portion of the African continent just below the equator, is Africa’s second-largest country by land area and the fourth-largest by population. Its territory incorporates people from more than 200 ethnolinguistic groups, each with distinctive cultural traditions. Though estimates of its Catholic population size vary, the DRC is home to the largest Catholic population in Africa and the seventh-largest in the world.1 It is also home to the largest and arguably most sweeping project of deliberate inculturation in the Catholic Church in the last century, integrating local African ways of praying and interacting with Catholic liturgy and formation.

Decades of conflict between rival armed militias and interference from neighboring states have led to the deaths of some 6 million people and the displacement of 6.5 million more in the eastern part of the country, but other parts of the country including the capital, Kinshasa, are more stable.2

The country faces enormous economic and political challenges, but religious life is vibrant. Though it has lost members to Evangelical and Pentecostal churches in the last decade, the Catholic Church is a powerful, stabilizing force in Congolese society.

Rather than aim to encompass all of the country’s diversity, the articles here focus on the western city of Kinshasa, which has its own local culture and story and is a magnet for people from every local culture in the DRC. Nearly 17 million people—one-fifth of the DRC’s population—live in Kinshasa. It is the largest city in Africa and is the political and cultural capital of the country.3 Kinshasa is located on the south side of the Congo River, about 400km inland, directly across from the city of Brazzaville, the capital of a different country, the Republic of Congo. Lingala and French are the common languages in Kinshasa, the latter for government, education, and formal business, the former for day-to-day conversation.4 Churches in middle and upper-class communities conduct liturgies in French, while many others in poorer areas celebrate in Lingala. Occasionally, too, celebrants switch from one language to the other.

Kinshasa is a sprawling city whose many informal sector workers labor where the formal sector often fails. Demographically, it is a youthful city, full of schools and young people. Life expectancy is low by global standards and families are relatively large.5 The average age is 24, but “more than half of those in the 15–34 age range [are] unemployed.”6 The city’s often-battered streets and sidewalks are clogged with people offering motorcycle taxi rides or eagerly selling drinks, clothes, and other goods. Foreigners could initially perceive many street scenes as chaotic but, upon closer observation be equally struck by how entrepreneurial young people are or how improvisational the culture is.7 Interviewees, taxi drivers, and others lamented the disorganization of the city and the failures of the political class, but one part of life seems well-structured and well-regarded: the Catholic Church.8 Its liturgies, which engage large numbers of lay people in formal roles, are organized better than in most places in the world, and Catholic schools are sought-after. As one interviewee reported, “The largest and best schools here are Catholic. People prefer them, even those who are not Catholic… new private [schools] pick Catholic-sounding names to pretend that they are as good.”

Historical Background

Pre-colonial life among so many different ethnic groups in such a vast country is difficult to summarize adequately. Some peoples were organized under fairly complex political structures headed by kings, while others were members of smaller-scale tribal arrangements. Some ethnic groups were known far-afield for their high-quality metalwork; all seem to have been engaged in intricate trade networks. Their eventual legal unification into a huge, single state was the outcome of European power politics, not a process initiated from within the territory.

The first Christian evangelization in the area around present-day Kinshasa dates to the end of the 15th century. Nzinga a Nkuwu, ruler of the Kingdom of Kongo, a remarkable coastal kingdom centered in what is now Angolan territory, was baptized in 1491. The kingdom ruled over people and territory from the Atlantic coast to as far east as present-day Kinshasa.9 Nzinga a Nkuwu’s son, Manikongo (King) Afonso I vigorously embraced Catholicism and fostered the growth of the Church there. Pope Leo X ordained Afonso’s son Henrique a bishop in 1518, making him the first Catholic bishop from sub-Saharan Africa.10 Some evidence suggests that the Church was most successful in the higher political echelons of society. Still, it is also notable that Catholicism flourished even without many missionaries or indigenous clergy. One historian describes it as “uniquely shaped and maintained by Kongolese laity, causing the faith to take root as a local rather than a foreign faith, informed by Kongolese language and culture.”11 Catholicism and the kingdom that supported it were undermined by several factors, including the insatiable desire of the Portuguese for slaves and European power machinations.12 Nonetheless, the Christian culture developed here is remembered to the present day. In 1665, a battle with the Portuguese dealt a definitive blow to the Kingdom and to the Catholic infrastructure it supported.13

Though the Congo River is one of the largest in the world, a series of waterfalls and intense river rapids prevented Europeans, including missionaries, from reaching far beyond Atlantic coastal areas. In the 1870s, Europeans in search of ivory bypassed the rapids and traveled further inland, including to Kinshasa. Protestant and Catholic missionaries soon followed, at first in small numbers.

At the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, European powers drew maps that carved up Africa along political boundaries still salient today. Leopold II, the King of Belgium, gained control of a huge area of land incorporating many peoples, which he named the Independent State of the Congo. A trading post at the river’s Malemba Pool was christened Léopoldville in 1881. It became the capital in 1923 and today is known as Kinshasa. France gained control of the territory north of the river, now incorporated as the Republic of Congo. In the Belgian Congo, both Protestant and Catholic missionaries were active from the beginning. Missionaries from the Congregation of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, commonly known as the “Scheutist” Fathers, arrived in 1888 and served as the primary missionary group, but all evidence suggests that Congolese lay catechumens played a tremendously important role from the earliest days, accomplishing what missionaries never could have done alone.14 In a 1908 concordat signed with Leopold, the Vatican conceded that all Catholic missionaries in the territory had to be Belgian.15

Leopold’s “Free State,” run independently of the Belgian government as a private fiefdom, brutalized and effectively enslaved the population to extract ivory and rubber while developing no infrastructure other than for extraction. Ships left Africa full of ivory or rubber and returned from Europe with only military cargo. Leopold’s plunder resulted in “a death toll of Holocaust dimensions,” “estimated at ten million people.”16 Catholic missionaries “never truly opposed the regime.”17

Under pressure, the Belgian government assumed control in 1908. It exported copper, uranium, and other metals, but still provided little in terms of social services directly. By all accounts, the Church in Congo developed as a “colonial-Catholic alliance.”18 The Church, with state support, provided the vast majority of educational and health services that the state had little interest in providing.19 Hastings asserts, “Catholic missionaries [in the Belgian Congo] used their privileged status to convert by little less than force, compelling children to attend school, converts to attend the catechumenate, everyone to conform to the moral law as interpreted [by the missionaries.] Nowhere else in Africa, Hastings says, was so much force used, even in the 1930s and 1940s, to achieve a religious end as in many Belgian Catholic missions in the Congo.”20

The educational system deliberately prepared Africans only for minor and mid-level roles in a Belgian-led political and economic system.21 Job opportunities for Black Congolese were limited to subordinate roles.22 Catholic seminaries were plentiful and represented the best opportunity for post-secondary education, but many Congolese did not continue to ordination.23 The first Congolese university, the Jesuits’ Lovanium, opened only in 1954.24 The Church went further than any other institution to provide for the well-being of the people, but “[W]hile no country had more African priests than the Congo, in no country was there greater reluctance to appoint them to the episcopate.”25

In 1956, a Belgian scholar published a plan proposing merely to create conditions to enable Congolese independence thirty years in the future. Belgians vehemently rejected even that idea, but it catalyzed a group of Congolese graduates of the Scheutist schools, led by a Congolese priest, Joseph Malula, to respond with a powerful and ultimately influential manifesto, Conscience Africaine. Written in the form of a Catholic encyclical, it called for a more immediate, peaceful end to colonial rule.26 Malula was appointed auxiliary bishop in 1959 and proclaimed at his ordination, before the country achieved independence and before the reforms of the Second Vatican Council even discussed inculturation, that it was time to shape “a Congolese Church in a Congolese state.”27

Independence

Independence was achieved one year later, in 1960, but the country’s unity was threatened from the beginning by a lack of preparation, foreign meddling, domestic political fragmentation, and regional secession.28 The first post-colonial government was overthrown in a coup within months and the first Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, was assassinated. In 1964, Malula was appointed Archbishop of Kinshasa (still known as Léopoldvile) amidst the ongoing political crises. Joseph Désiré Mobutu, a leader of the earlier coup, consolidated power and seized control of the country in 1965, ruling a corrupt and failed one-party state and changing the country’s name to Zaire. Mobutu died abroad in 1997 just as civil war was engulfing the country. The country’s name was changed back to the Democratic Republic of Congo. A re-eruption of civil war from 1998 to 2003 claimed millions of lives through war and famine.

When the DRC achieved independence in 1960, the diocese of Léopoldville, headquarters of the Scheutist mission, had only three Black Congolese diocesan priests in what was then a city of 400,000.29 Hastings reports that missionary clergy and religious women were highly supportive of Black bishops when they were named and behaved admirably during the political chaos of the early 1960s.30 Until a larger corps of Congolese clergy could be built, during a time when missionaries’ presence was sometimes politically tenuous, the archdiocese of Kinshasa developed a system of Congolese lay headship in each parish, This system faded when there were eventually enough Congolese priests to take charge. Catechists were similarly important in ensuring continued growth and education.

While the relationship between Mobutu and the Church started well, it became oppositional. Both Mobutu and Malula wanted to forge a strong post-colonial identity for the country, but Mobutu’s way of doing so was focused on reinforcing his own power. He came to see the Church as a threat and cracked down on the Church nationwide, nationalizing the Lovanium, hospitals, and schools and attempting to implant party control in all institutions, including the seminary. He forbade the use of Western Christian names both at baptism and in daily interactions, outlawed teaching religion in schools, closed religious newspapers, and even banned the celebration of Christmas. In 1972, he exiled Cardinal Malula, his most prominent critic, for five months. Faced with crises in the educational sector, Mobutu was forced to relent. His policies failed so badly that the Church emerged in the wake of the conflict as an even more influential institution, responsible for an even greater share of education and healthcare in the country as people fled poorly resourced state institutions.31

Under Malula, the 1960s-1980s were a time of remarkable work to develop a Catholic authenticité that reflected Congolese cultural values. Most notable among these is the “Zairian rite” liturgy, but one could also add the foundation of youth and young adult formation programs like Bilenge ya Mwinda and efforts to enhance the visual and musical elements of Catholic life in ways distinctively Congolese.

In the face of autocracy and corruption, the Church was often an oppositional force in Zairian political life while also being interwoven in government.32 It remains the only serious independent force with national influence. In the late 1990s, after Mobutu was overthrown and in the absence of credible alternatives, Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya assumed a leading role on the country’s transitional political commissions. Lay Catholic groups have played a critical role when some bishops hesitated to push harder. In 2017, when President Joseph Kabila refused to step down at the end of his term, the Catholic Bishops’ Conference negotiated elections while priests and lay Catholics led crucial street marches. The Church marshaled a huge force of election observers. This led to the country’s first, though still compromised, peaceful transfer of power.33

The Church is still relatively vocal in political matters, not in formally backing candidates, but in speaking out from time to time about corruption and encouraging democratic government. On Easter Sunday 2024, during this research, Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu spoke from the pulpit against the government’s failures and was called to face a judicial investigation into whether he was thereby punishable for sedition.

It bears noting that a remarkable proportion of the Catholic Church’s growth occurred not in the first half of the modern era of Christian evangelization, under colonial rule, but in the last half, primarily during post-independence years. The World Christian Database reports that in 1900, there were fewer than 75,000 baptized Catholics in the Belgian Congo, representing 0.8% of the population. In 1950, that number reached 1 million, 8.1% of the population. By 2000, the number had grown to more than 27 million, representing 55.7% of the population, and in 2020, by their count, there were more than 49 million baptized Catholics in the DRC, 53% of the population.34

Huge growth among other Christian Churches has also transformed the religious landscape. Evangelical churches began to proliferate in 1979, proselytizing heavily among young people and drawing a significant proportion of them.35 One priest suggested that while Catholicism was once the religion of 70% of the population, today, by all estimates, fewer than 50% of all Congolese identify as Catholic. Many of the Catholics interviewed here were critical of the ministers in Evangelical churches for being too prosperity-loving. “They know people like prosperity,” one Catholic layman said. Others noted how many elements of Catholic practice Evangelical churches borrowed. Whereas Catholic churches are huge and often located some distance from each other, small Evangelical churches are tucked everywhere in neighborhoods. Another interviewee explained that they are “churches of proximity,” unlike large Catholic parishes.

Contrasting Post-Independence Legacies

Without overlooking the distinct challenges that the Catholic Church in the DRC faces, Church and state in Kinshasa are a study in contrasts. Malemba’s leadership of the church was as successful as Mugabe’s leadership of the country was ruinous. Mobutu largely preserved the territorial integrity of the country but at a huge cost. “The popularity of the Church is linked to its ability to fulfill the functions of the state itself, not only as far as education and healthcare are concerned… The ability of the Church to step in for the lacking public services is essential to understanding why the Church plays an incomparably higher role in Congolese politics” than in other countries.36 Still, several interviewees were ready to note that the Church has to grapple with the fact that many of the elites it educated are the same people whose corruption diminishes life here.

Congolese priests have almost entirely replaced missionary priests. An even larger number of religious sisters, many in African-founded orders, provide many services in schools and clinics. Seminaries are large and full, but with such a growing population, the ratio of priests and sisters to laypeople is still rather low. While many priests are assigned to each urban parish, their numbers have still not kept up with overall population growth. With more than 8,000 baptized Catholics per priest, each priest in the DRC needs to serve about four times as many Catholics as a priest in the U.S. or Spain.

Congolese interviewees were aware of the shortcomings of colonial history, even as they were grateful to have been exposed to the Gospel. One man simply said, “This is the problem of the colonizers. They will be responsible before God. The message, the Word, belongs to the people here. It is not something that belongs to the colonizers. Because God is able to operate in different ways.” But he also admitted that the disconnect between what is taught from the gospel and what colonizers did certainly prevents some contemporary Congolese from believing. Insofar as his comments are representative, they should not be taken to mean that believers thought that all the questions of colonialism and racism belong to the past. When a group of diocesan priests was asked in passing what African cardinal would make the best pope after Pope Francis, one laughed at the question. “There won’t be a Black pope. Maybe an African, but never a Black one.”

Authenticité today: Traditional and Modern; Cosmopolitan and Linked to Village Cultures

Like all cultures, Kinshasa’s culture is in flux. People embrace a variety of aspects of modernity but also search for ways to be authentic by traditional Congolese standards. In many ways, it is fair to say that the version of modernity being shaped in Kinshasa is a particularly Congolese one, not simply a copy of some Western version.

Whatever the Congolese Church’s successes at inculturation, belief in it has never been uncritical. This was apparent in the ways that several interviewees spoke about traditional cultural elements they were sometimes hesitant to see included in the Zairian rite or ways that they thought about what modernity had given and taken from them. Others were wary about more contemporary musical styles creeping into church choral music. Speaking of traditional culture, one said, “We take what is good, because in culture, there is not only what is good. There are other bad things too. What is bad, we criticize. And what is good, we recover this to also serve [the faith].” One example of the critical treatment of traditional culture is evident at Villages Bondeko, a Catholic charitable community for deaf and other handicapped people, where the Church has worked to overturn, in the name of justice, traditional attitudes about deaf and handicapped people. People there said they also work to overcome traditional attitudes towards gender, making sure girls were treated as equals by boys. On the other hand, Congolese sign language, which was developed at Villages Bondeko, is not simply an American or French import, but one whose signs are in step with traditional Congolese cultural symbols.

Given Kinshasa’s growth into a megacity, its status as a cosmopolitan city that draws people from many Congolese cultures, and the fact that the majority of young people are at least a generation or two removed from ancestral villages, the question that remains is how authenticité, not as a political project, but as a lived aspiration, is being reshaped. What cultural forces, traditional or modern, do Catholics, among others, look to now to decide what makes them “authentic”? The question of authenticity is hard to explore head-on, but oblique evidence hints at the complexity.

In the earlier post-colonial period, authenticité inexorably drew on traditional culture. Many of the religious forms that define Congolese Catholic life—the Zairian rite liturgy and Bilenge ya Mwinda among them—grew out of an early postcolonial desire to shape a Church and society grounded in traditional culture, which was village-centered.

One young person, two generations removed from the villages of his ancestors, reported, “more and more, Kinshasa is also starting to lose ancestral values.” A middle-class woman perceived a big gulf between Kinois (Kinshasans) and their villages of origin. “Now, my kids, they would not go there. They would not like going there. Because they are in Kinshasa, you don't know how [to] behave there in the village… [The villagers] get jealous [when they meet family from the city]...in some places where I've been, in Abidjan… people they won't go [out in the countryside] because people put curses on people out there.” Another woman reported that more educated urban parents were now likely to have relatively smaller families—3-4 children—in order to educate them. Still, village-of-origin rules are likely to define life events like marriages, which can still require some form of dowry prescribed by a particular culture and negotiated by families. Getting married often still requires a traditional ceremony plus a Catholic one and a visit to a registry.

Another Congolese man shared his conviction that it’s foolish to think of Kinois, even if they dress in Western clothes and aspire to Western things, as people who think in Western ways. The story about curses says something about the challenges here. The woman who shared it repeatedly distanced herself by explaining how the villagers are very different because they are not “developed” and have different ways of behaving. But when it came to curses, she shared the same fear as people in the villages.

By all accounts, the Zairian liturgy, built in part on traditional village practices, remains integral to Catholic worship here, as is the incorporation of dance and choral music as forms of prayer, though the style of the latter may change. Charismatic forms of worship seem to have a draw both insofar as they involve modern, media-oriented practices and associations—including enabling prosperity—and insofar as they are believed to provide powerful healing and protection from evil forces, two deeply traditional purposes of religion in the DRC.

None of the changes in Congolese life show signs of yielding significantly to secularization of consciousness. Even in a modernizing urban context, belief in a God who is active and relevant runs “deep in Kinois identity,” as one interviewee framed it. As one historian recounts it, when the Kongo people first encountered Christianity five hundred years ago, people believed “that it was the powers in the other world that caused all the good and evil perceived in this world.”37 In 2024, interviewees ascribed the same propensity to Congolese people. As one person summarized, not believing in Jesus is possible here, but “not believing in God is difficult. How can you be protected from evil forces if God does not exist? So it's very difficult for an African who grew up here not to believe in God. It's very difficult.”

- 1The Pew/Templeton survey cited in the chart on the Catholics & Cultures heading page for the DRC claims that 30.1% of the population is Catholic, but a different Pew/Templeton study, “Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa,” claims that the DRC is 80% Christian, 12% Muslim, 3% adherents of traditional African Religions, and 4% unaffiliated, and that 46% of the DRC’s Christians are Catholic, which would suggest that 36.8% of the population is Catholic. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa (Washington, D.C.: Pew Research Center, 2010), 20, 22. A revised Pew study in 2013 claimed that 47.3% of the population is Catholic. Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, Global Christianity: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Christian Population, December, 2011, revised 2013, p. 23, accessed October 31, 2024.

- 2On the ongoing war in the East and its costs, see Declan Walsh, “The Overlooked Crisis in Congo: ‘We Live in War’,” The New York Times, Dec 17, 2023.

- 3City size rankings depend on whether full metropolitan areas are included. If they are included, Cairo is larger than Kinshasa.

- 4Lingala is a Bantu language revised from indigenous roots to be a lingua franca, a language that could allow speakers of different tribal languages to engage each other. In the early 20th century, Belgian Scheutist missionaries reconstructed Bobangi, a local trade language, as a modern language expressing concepts suitable for evangelization, teaching it in their schools. French was also used by the colonial authorities in the same way and is used throughout the country. Both languages can be heard on the streets, though French is used for education and a great deal of official work. In churches visited for this research, Lingala was most commonly used, but French was interspersed. On the process of development, adaptation, and resistance to Lingala, see Michael Meeuwis, “Involvement in Language: The Role of the ‘Congregatio Immaculati Cordis Mariae’ in the History of Lingala,” The Catholic Historical Review 95, No. 2 (2009), 240-260. One priest-interviewee suggested that the common adaptation of Lingala arose because of “President Mobutu, who made Lingala the language of the army. And that's why now almost everyone in Congo understands Lingala.”

- 5For graphics on the population distribution and life expectancy nationwide, see “Population, Democratic Republic of the Congo,” Data, World Health Organization.

- 6Héritier Mesa, “Precarious Youth and Everyday Improvisation in Kinshasa,” Current History (2024), 123, 163.

- 7My own impression centered on the entrepreneurial quality of life. “Improvisational” is an equally good phrase borrowed from Mesa, “Precarious Youth and Everyday Improvisation in Kinshasa,” 163-68.

- 8In addition to the published sources cited here, these articles are based on interviews and research in Kinshasa from March 24 to April 7, 2024 at eight parishes: la Cathedrale de Notre Dame du Congo, Reine des Apôtres, St. Alphonse, Ste. Anne, St. Joseph, St. Pierre, St. Raphaël, and Sacré Coeur; at Loyola University of Congo and at a community for the deaf and handicapped called Villages Bondeko. Special thanks are due to Fr. Emmanuel Bueya, SJ, for help setting up the itinerary and for making many introductions, to Axel Kiangebeni for accompaniment, guidance, and translation throughout, and to the many interviewees who took time to talk.

- 9For more extended English-language discussions of Catholic engagement in the Kingdom of Kongo from the first European and Christian contacts through its demise and final subjugation in 1665, see John K. Thornton, Afonso I Mvemba A Nzinga, King of Kongo: His Life and Correspondence, Indianapolis, Hackett, 2023; Anne Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo (Oxford: Clarendon, 1985); Adrian Hastings, The Church in Africa 1450-1950, Oxford: Clarendon, 1994, 71-129; and Bengt Sundkler and Christopher Steed, A History of the Church in Africa (Cambridge University Press 2000), 49-62. For an older Church-sponsored publication on the history on the Church in French, see L’Eglise Catholique au Zaire: un siecle de croissance, (Kinshasa-Gombe: Edition du Secretaire-Genérale de l’Episcopat, 1986).

- 10Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo, 136-37.

- 11Sara Fretheim, “Early Central African Christian History: Prophets, Priests and Kings” in The Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa, ed. Elias Kifon Bongmba (Routledge, 2016), 96-99.

- 12On aspects of Catholic practice and its relationship to political power, see Kwang-Su Kim, “The Historical Contextualization of the Congo Kingdom in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s History” in The Democratic Republic of the Congo: Problems, Progress and Prospects, ed. Julien Bobineau Philipp Gieg (LIT: 2016), 37-41.

- 13For insight into the complexities of that decline, see Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo, 142-224.

- 14Sundkler and Steed credit much of the growth of Congolese Catholicism to an “army of village catechists: 7,660 with eighty-five women in 1923, 20,000 in 1959, and by 1961 some 163,000 and no less than 2,600 [European] sisters with 910 African sisters” Sundkler and Steed, A History of the Church in Africa, 768-769. They recount very early examples in detail as well, 296-302.

- 15The concordat remained in place when the Belgian state assumed control from Leopold.

- 16Adam Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror and Heroism in Colonial Africa (New York: Mariner, 2020), 4, 280.

- 17Jairzinho Lopes Pereira, “The Catholic Church and the Early Stages of King Leopold II’s Colonial Projects in the Congo (1876–1886),” Social Sciences and Missions 32 (2019): 83. Pereira’s article discusses the early involvement of Catholics there and ascribes a range of motivations, including evangelical, “civilizing,” and anti-slave trade orientations (91) that impelled it.

- 18Hastings, The Church in Africa, 462.

- 19Adrian Hastings, History of African Christianity 1850-1975 (Cambridge University Press, 1979), 19. Hochschild notes ways that Protestant missionaries were instrumental in calling attention to the horrors, but does not cite any similar Catholic examples, if they existed. Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 172-221.

- 20Hastings, The Church in Africa, 563.

- 21The educational system certainly aimed to Europeanize and Christianize Congolese. Still, Congolese Catholic interviewees consistently credit the Church for continuing to provide quality education while the state falls far short. Catholic schools helped in many ways, interviewees all agree, but were not designed to help enough. The colonial-era system only imagined Africans in “helper” roles and did not educate Africans for leadership.

- 22Gertrude Mianda, “Colonialism, Education, and Gender Relations in the Belgian Congo: The Évolué Case,” in Women in African Colonial Histories, ed. Jean Allman, Susan Geiger and Nakanyike Musisi (Indiana University Press, 2002). Seminaries were the exception in terms of educational opportunities, though the number of Congolese clergy was modest, and Black Congolese clergy were often not treated as equals by White missionary clergy.

- 23Hastings, History of African Christianity 1850-1975, 172.

- 24The university gathered together previously founded post-secondary institutions like an institution for medical assistants and an agricultural school.

- 25Hastings, History of African Christianity 1850-1975, 170. Sundkler and Steed report, “By 1950 the four major theological seminaries, begun in the 1930s, had produced 154 African priests and, ten years later, 400.” Léopoldville/Kinshasa was behind the curve. Bengt Sundkler and Christopher Steed, A History of the Church in Africa, 766.

- 26On the ecclesial characteristics of the document, see Isidore Ndaywel è Nziem, “Aux Origines de l'Éveil Politique au Congo Belge: une Lecture du Manifeste Conscience Africaine (1956) Cinquante Ans Après,” Présence Africaine, no. 173 (2006): 127–44.

- 27Malula was ordained an auxiliary bishop in 1959 in the city’s football stadium and was appointed archbishop of the city in 1964. The first Black Congolese bishop of the modern era was Bishop Pierre Kimbondo, ordained as auxiliary bishop of Kisanto in 1956 and appointed as head of that diocese in 1961. Malula was elevated to the rank of Cardinal in 1969.

- 28For example, only Belgian, not Congolese, had been allowed to be officers in the local police and military, a condition that was imposed even after independence until a mutiny undid it.

- 29Those numbers were reported by some older diocesan clergy during interviews. While the Belgian Congo led the continent in the number of native clergy, many of those were in religious orders. Hastings reports that there were 100 native Congolese priests in 1950, but half of those were Jesuits, not parish priests. Hastings, History of African Christianity 1850-1975, 63.

- 30Hastings, History of African Christianity 1850-1975, 171. Four priests, three European and one of French and Congolese heritage, were beatified in 2024. ACI Africa Staff, “Blood of Four Newly Beatified Martyrs ‘seed for the profound evangelization’ in DR Congo, Globally: Cardinal Ambongo,” ACI Africa, August 18, 2024.

- 31Petr Kratochvíl, Geopolitics of Global Catholicism: Politics of Religion in Space and Time, Routledge Studies in Religion and Politics (Routledge, 2024), 189. As institutions have rebuilt, the Catholic share has shrunk but is still very large.

- 32J.J. Carney, Christendom in Crisis: the Catholic Church and Postcolonial Politics in Central Africa” in The Routledge Companion to Christianity in Africa, ed. Elias Kifon Bongmba (Routledge, 2016), 365-378. For a survey of some of the bishops statement in the first decades after independence, see Raoul Kiyangi Meya, “L'Engagement Sociopolitique de I'Église Catholique au Congo-Kinshasa,” in The Democratic Republic of the Congo: Problems, Progress and Prospects, 167-182.

- 33For more about the Catholic involvement described here, see Laurent Larcher, L’Église en République Démocratique du Congo: (encore) face a pouvoir (Paris: Ifri, 2018), 7-12; and Groupe d’Étude sur le Congo et Ebuteli, L'église catholique en RDC: au Milieu du Village ou au Coeur de la Contestation? (Le Groupe d’étude sur le Congo, 2022).

- 34Gina A. Zurlo and Todd M. Johnson, eds., World Christian Database (Brill, 2023), as cited in Petr Kratochvíl, Geopolitics of Global Catholicism, 164. Other studies suggest that the current proportion of Catholics is smaller in recent years, but the WCD study focuses on baptized Catholics, who may in fact be attending other churches.

- 35“Bilenge Ya Mwinda à Kinshasa: 10 Ans Bilan” no author, typescript (Bibiliteque CEPAS, Kinshasa), 6.

- 36Petr Kratochvíl, Geopolitics of Global Catholicism, 164.

- 37Hilton, The Kingdom of Kongo, 9.