Immigration shaped the Danish Catholic church from its re-foundation in the 19th century. Since the 1970s Danish immigration has increased significantly, changing the complexion of Danish society. According to the Diocese of Copenhagen, “approximately one third of all Danish Catholics have been born abroad. In addition, a number of Catholics are born in Denmark of foreign parents.”1 Danes and Danish Catholics have had to think about their identity in light of an influx of people with values and practices different from theirs. This may be part of the reason why secular Danes are willing to financially support “traditions” like Lutheran churches, clergy and choirs, as an essence of “Danishness,” even if they don’t really believe in Christianity.

Denmark was Catholic from late in the first millennium until 1536, when it became a Lutheran country under the authority of the crown. Catholicism was given a small foothold in the 19th century to allow for the religious needs of foreign diplomats in Copenhagen, and then grew from there largely through the work of foreign missionaries. To speak of “Danish Catholics” is most often to speak of people who had one or more parent or grandparent who immigrated to Denmark a generation or two ago. These Danish Catholics are Danish not only in terms of citizenship, but also in that they have been raised in a Danish context, with Danish cultural values.

Some Danes say privately that Danes tend to be intolerant of foreigners, and others point to challenges that they feel as more socially conservative immigrants, including clergy, come to represent the face of Catholicism.

In the Copenhagen metropolitan area, Masses are conducted weekly at a number of churches in Polish and English, and at least once a month in Ukrainian, Croatian, Chaldean, French, Spanish, and Italian.

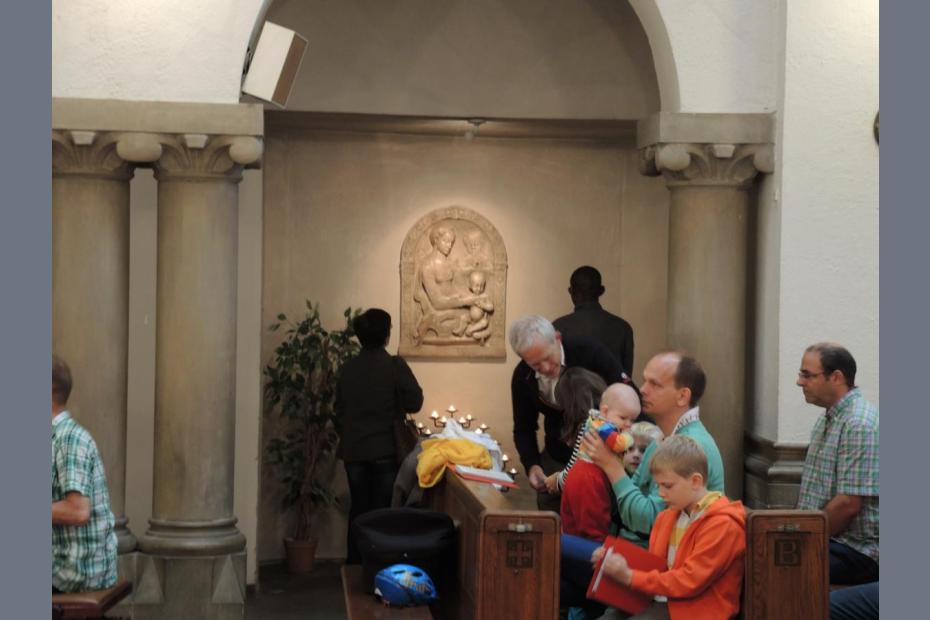

Though there are no clear figures, many Danes in Copenhagen suggest that persons born in other countries constitute the majority of Catholics attending liturgies. Sankt Annæ (St. Anne’s) Parish, in working and middle-class Amager, is in essence three communities: a community that attends a Danish language liturgy on Sunday morning in a half-filled church; a large Polish community, composed particularly of Polish men who had come in search of work, which fills the church at mid-day; and an English speaking, largely Filipino community that fills the church at 5 p.m. The parish, staffed by Redemptorist priests from Poland and Kerala, India, is making new efforts to bring those three communities together at least occasionally. Even at the Sacramentskirchen’s Danish Mass, a quarter of the 100 participants at liturgy hailed from Africa, East Asia, India, and the Middle East.

A parish study conducted in 2011 suggests that integration may be a problem. It suggests that in 12 of 30 parishes, more than half of attendees attend non-Danish Masses, and that foreigners form their own communities, rather than integrate. The Polish community is said to be isolationist, not mixing with other Danes as much, including at church, or learning the language, unlike most other immigrant groups.

Several Danes reported that people from more vibrant and outward faith communities in Africa and the Philippines get a “faith shock” when they move to Denmark. Many say their frequency of worship lessens because they feel adrift in such a quiet, contained mode of worship. One Catholic parish is beginning to find ways to minister to Africans in their own modes of worship, with French and English African choirs, a Uganda martyrs celebration, and other events.

Some of the practices of the immigrant churches highlight, by contrast, characteristics of Danish Catholicism. At St. Anne's in Amager, dozens of parishioners line up after Mass to ask for blessing from the priest or a special prayer for a specific issue. Most Danes say they respect this, but see it as something they would never do.

There is a fairly large Filipino community in Denmark, especially visible at the English-speaking service at St. Anne’s in Amager. The situation of the Filipino migrants differs significantly from that in Hong Kong. In Denmark, more Filipino migrants come as whole families. Many young women do come as au pairs, on two-year exchange contracts, but unlike Hong Kong, some of these women end up dating Danish men, bring them to the Catholic church and raise their children Catholic.

- 1"The Catholic Church in Denmark," katolsk.dk, last accessed April 1, 2014, http://www.katolsk.dk/1635.