Kate Goza '20, a student at the College of the Holy Cross, writes from her year abroad in Florence, Italy. Thus far, she has most enjoyed walking around the Duomo at night and exploring the Tuscan countryside. In the months ahead, she looks forward to traveling more around Italy and beginning research for her cultural immersion project on a Renaissance mystic. Kate, who comes from Seattle, is studying comparative religion and Italian at Holy Cross and hopes to pursue a career as a professor.

Italy and tradition

One of the reasons why I wanted to study abroad in Italy was the promise of experiencing a country whose culture is so steeped in a single religious tradition. Walking around Florence for the first couple of weeks was surreal because my sight line was constantly being dominated by religious imagery, from shrines to saints in the niches of random buildings to the hundreds of year old churches around every corner. Living within this new type of religious sphere made me even more curious about participating in an Italian feast day or festival firsthand. With this in mind, I decided to set out to experience how All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day would unfold against the backdrop of Florence.

Setting the scene

All Saints’ Day, commonly called Ognissanti, and All Souls’ Day, il Giorno dei Morti, take place on the first two days on November. In Italy there is a ponte, or long weekend, where there is no school or work so people are free to observe these days. Ognissanti is celebrated in honor of all known and unknown saints. Its date of November 1 can be traced back to the papacy of Gregory III (731-741) when he dedicated a chapel at St. Peter’s in Rome to all saints. The festivities for Ognissanti are more subdued than the following day and usually involve attending Mass.

All Souls' Day, il Giorno dei Morti, marks a transition from the commemoration of the intangible lives of saints to that of the more tangible deaths of one’s loved ones. My only frame of reference for understanding il Giorno dei Morti was what I learned about the Mexican Día de los Muertos in my high school Spanish class, through the vibrant images of ornate altars and graveside decorations. The Florentine iteration of this feast day is more restrained, but is still centered on making the trek to one of the city’s cemeteries to tend to the graves of family members with bundles of flowers in tow.

The Church of All Saints

Because Ognissanti seems to be overshadowed by il Giorno dei Morti, there was not a clear path to follow in order to observe the holiday. But, I thought it would be appropriate to visit the church in Florence that is dedicated to all saints: La Chiesa di San Salvatore di Ognissanti. On my way to the church, I noticed that there were many more families walking around together than usual and people socializing in the streets. It struck me that this ponte had a social dimension that went alongside its overt religious one.

La Chiesa di Ognissanti is situated in a piazza that looks out across the Arno River that runs through Florence. The church itself was built in the 1250s by a lay order called the Umiliati and was later taken over by the Franciscan order in 1571, but its most famous historical detail is being the resting place of Sandro Botticelli. I made my way into the church surrounded by other small groups, some tourists and some Italians. The Baroque architecture of the church’s interior was staggering with my gaze being drawn first to the framed altar and then up to the painted ceiling. The sides of the nave were flanked with frescoes by such masters as Giotto, Ghirlandaio, and of course Botticelli.

Interspersed between these works were extremely lavish shrines to a handful of different saints. Each had fresh flowers before it in honor of the feast day, a foreshadowing of the use of flowers the following day. A statue of Saint Anthony was particularly striking as it rested behind a glass-sealed alcove which was decorated with swirling marble details of flowers mimicking the real flowers that had only been there a day.

After exiting the church I was greeted once again by the sight of many Italian families out for a stroll together in the dusk. Visiting a church like this one on Ognissanti is a way to quietly reflect on the holiday itself, but for me was also a catalyst for thinking about how occasions such as these are truly a window into the subtleties of an unfamiliar culture.

Souls and cemeteries

The next day, All Souls’ Day, draws a higher degree of participation from the local population. It is a day to remember those who have died in one’s family and to visit their gravesides. The previous week I had asked my Italian teacher where I should go if I wanted to be an observer to the rituals of this day, and he told me that the best place would be il cimitero di Trespiano, Trespiano cemetery. Trespiano is the largest cemetery in Florence and was opened in 1784.

My journey to the cemetery on il Giorno dei Morti consisted of a bus ride up the steep hills that surround Florence. The city of Florence is in a valley and so when traveling outside of its confines one has the chance to enjoy views of the winding Tuscan countryside. Luckily I knew I had gotten on the right bus after seeing a pair of nuns and other individuals clutching flowers to bring with them to the cemetery. Snaking up the hills and leaving the city I felt like I was on some sort of strange pilgrimage taking on the role of a quasi-pilgrim and quasi-observer to this solemn task.

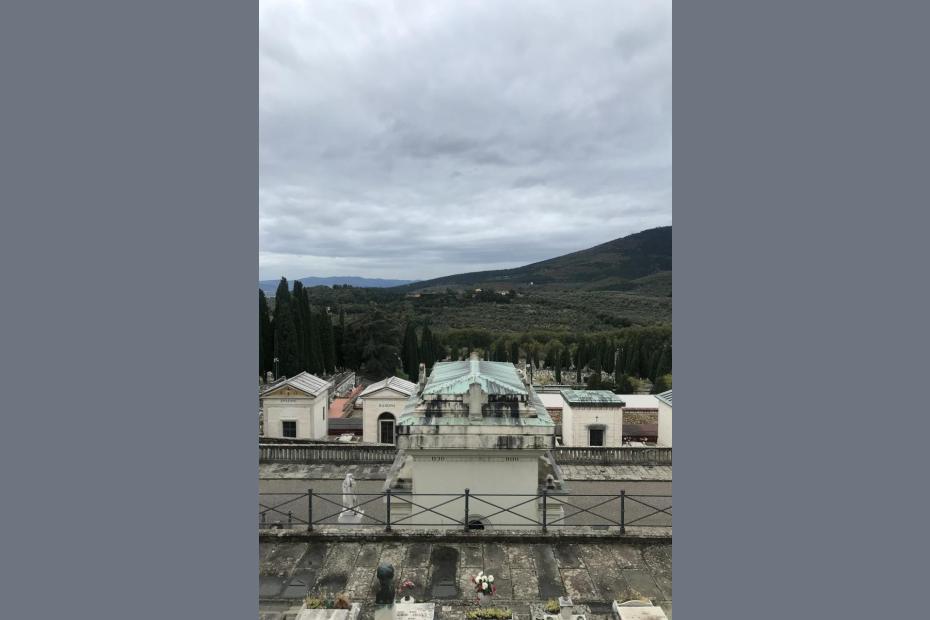

There was something about traveling up and being high above the city that made me feel isolated, as if I was crossing the barrier into some ethereal realm. I got off of the bus and followed the throngs of people into the cemetery whose gate is marked by monumental walls and a row of Cyprus trees that line a narrow path toward its main entrance.

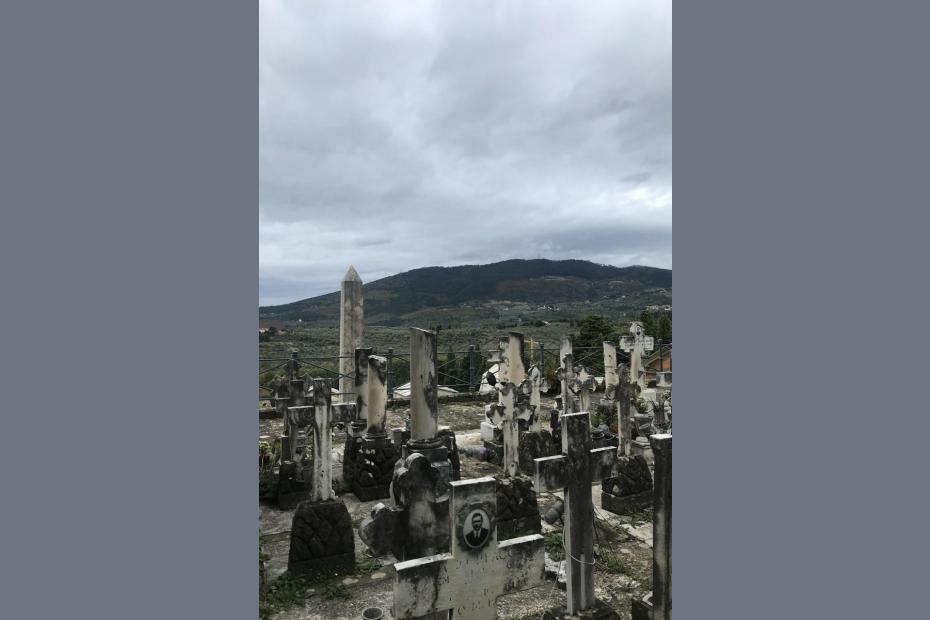

Reaching the end of the Cyprus path, I was taken aback by the absolute immensity of the cemetery. It was utterly staggering as hundreds and hundreds of graves erupted into a panorama of hills. The sense of immensity and depth of Trespiano is created by the fact that each section of graves or mausoleums is stacked upon the next.

The first thing that every visitor did before moving on to the cemetery proper was entering a small chapel to offer a quick prayer. Everything was done in a subdued silence with nothing louder than a hushed tone ever reaching one’s ears.

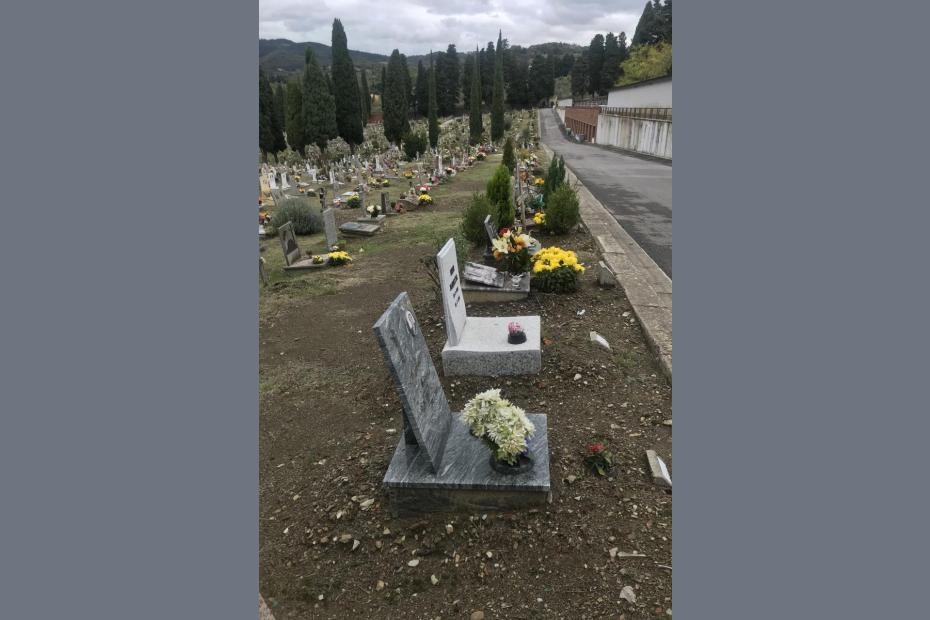

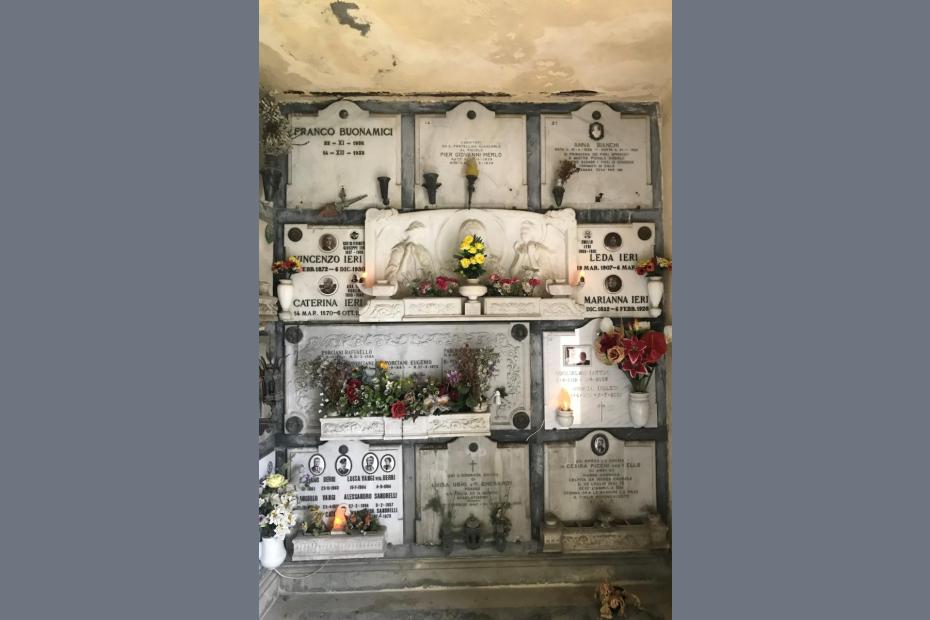

Almost every grave in the cemetery was adorned with flowers. It did not matter if the grave was new or dated back from the turn of the century. The sheer number of bouquets in every color and variety made for a true feast for the eyes.

The atmosphere of the day was one of an unspoken sense of community as couples and families milled about the white tombstones, the majority of which had been stained by time. But, these stains were not an ugly thing. I think that they were instead rendered sort of beautiful in their juxtaposition with the brightness of the offered flowers. The existence of both elements side by side, one death and the other life, seemed to attest to the delicateness of the line separating one from the other.

Later that day at dinner I was talking with my host mother and telling her about my outing. She then told me that she had gone with her sister earlier in the day to the same cemetery to bring flowers to the graves of her deceased family members. She told me about how going every year to Trespiano was an important way for her to reconnect with the history of her own family.

This idea of reconnection is at the basis of these two holidays. Both Ognissanti and il Giorno dei Morti provide platforms for reconnection, whether spiritual, historical, or cultural. My own observance of these days, as an outsider, gave me the chance to not only become more in tune with Italian cultural life, but also to deepen my understanding of the Catholic tradition that lies at its core.