Like many feasts, the pilgrimage to Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer includes moments of spectacle, intimacy, devotion, community fellowship, family time, commerce, and even occasions of conflict and competition. The May feast for the Saintes Maries and Sainte Sara is home to distinct, interacting communities — local believers, various communities of Gens du Voyage,1 other French pilgrims, and tourists curious to see a spectacle. Saintes-Maries-de-la Mer is a village of only 2,500 people. Even accounting for participants from neighboring villages, locals probably constitute fewer than 10 percent of the 25,000-40,000 attendees at the feast each year. By most accounts, the number of Gypsy, Tsigane, Manouche and other Gens du Voyage pilgrims was four to five times as large as the town population, but that still suggests that perhaps half of the people in town for the feast days were non-Gens du Voyage pilgrims and tourists. (It is not yet beach season, and hotels are expensive and in demand during the feast, so the feast itself is usually the “draw” that brings tourists here to watch.) French media — newspaper photographers and television crews, particularly evident at the Ste. Sara procession — add another layer of participants to the experience.

The Gens du Voyage can in one sense be seen as one of the communities represented, but the name in and of itself amalgamates a number of different communities that have a family resemblance but don't fully see themselves as one people. Gitans, or gypsies, are more closely associated culturally and historically with the Iberian peninsula; Manouches have a language and culture impacted by German culture; Yéniches are yet another group with Germanic culture and history. Roms - Roma - more recent immigrants from Slavic lands - complicate the picture, though this group, largely Pentecostal and Orthodox, is not visible at Sainte-Maries-de-la-Mer. On top of this a number of interviewees said that they did not like to think of themselves under any of these labels, that their identity and attachment was based first on family, and then on a way of life. 2

The Gens du Voyage interviewed during the feast in 2017 made clear that they came not to perform for outsiders — many said they resent being objects of touristic attention — but to pray and to be together in much greater numbers than they can be almost anywhere else.3 Though there were a few occasions when a small number of children were dressed in “Gypsy” clothes, and there was a display on the history of the feast and on Gypsy culture in a nearby conference hall, overall few of the Gens du Voyage dressed or performed "Gypsy" identities in public. Whether the Gens du Voyage wanted to be seen or not, the feast is a far from private event. In a place like Lourdes, the pilgrimage is public, but almost all observers can be presumed to be fellow pilgrims. At Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, in public spaces, statuses had to be regularly interpreted and negotiated. At the very least, given the nature of any pilgrimage and public procession, some collective religious “performance” is essential to a pilgrimage, but the experience is not intended to be the same as performing for tourists. Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer made them visible as Catholics, not least to each other.

Scholarly articles about the Gens du Voyage and the feast often explore this tension. Eric Wiley, a scholar of performance studies who has written about the Gens du Voyage’s participation in the feast, claims it is most fitting to regard the event as a form of public performance, where they “enact Romani culture for the tourists and for the millions viewing them on television in the same way that concertgoers at the Woodstock music festival in 1969 were performing an alternative, youth culture before local and national audiences.” 4 He notes, “Romanies have long embraced the roles and responsibilities of the performer, sometimes to the point of using the conditions of performance to frame their relations with outsiders… This may be seen in the way that Romanies as a whole are traditionally associated with cultural performances, (i.e. circus acts, bear-baiting, music and dance).”5

Given his own scholarly commitments and his expressed cultural unfamiliarity with the Gens du Voyage, Wiley may simply have found what he wanted to see. But he does draw attention to the paradoxes, to the fact that whether they want to be the center of outsiders’ attention or not, the Gens du Voyage are at the center of a deliberately designed public spectacle, and that it does frame the understanding of some outsiders.

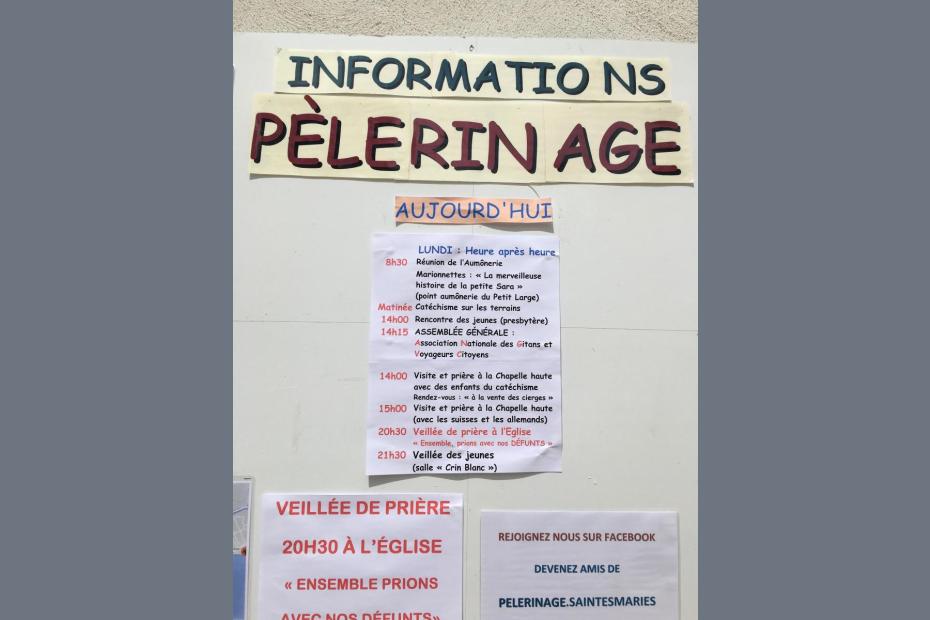

If not a performance, a question that remains is whether the Gens du Voyage and other pilgrims compete with other pilgrims, as if part of parallel or overlapping pilgrimages. The chaplaincy saves seats inside the church to ensure adequate space for Camarguaise and Gens du Voyage pilgrims. The Camarguaise have the Saintes Maries; the Gypsies have Ste. Sara. The Saintes Maries have their space above (and during the feast, on) the altar; Ste. Sara and her devotees have their space in the crypt. Each has a separate procession. The Marquis de Baroncelli, the lay Catholic who developed many of the rituals of the feast in the early 20th century, certainly worked to see to it that they are deeply interwoven. The chaplaincy still does the same. At certain moments, such as when the Gens du Voyage are greeting or praying at the reliquary of the Saintes Maries, or when clergy are praying together, Vivent les Saintes Maries! Vive Sainte Sara! the feast seems integrated. Many other moments, including Sara’s moment at the sea, or the closing Mass for Baroncelli, make the feast seem like a set of overlapping experiences for different groups. Even the division of space in town, between caravan parking areas and homes and hotels, while not a complete division, reinforces the differences.

Accounts vary about the welcome that the Gens du Voyage receive in Saintes-Maries-de-la Mer. Wiley’s account included a number of examples of conflict or fear both on the part of the researcher himself and the Santois population, as the natives of the town call themselves, describing it as a “tense situation” in 2001.6 In her interviews of locals and Gens du Voyage, Ellen Badone found evidence of disparate but parallel events, particularly during her interviews with Santois who either looked down on the cult of Sara, or regarded it with benign indifference, as something of value only for the Gens du Voyage.7 Several interviewees during the research for the present article (2017) indicated that they had to prod the town to live up to its legal obligations to provide sanitation and places for the camping trailers, but many also shared stories of good encounters, particularly with the gadjé (“outsiders,” non-Gens du Voyage) Catholics who volunteer to work with the parish and the chaplaincy to help make the event a success. Business was brisk in stores and restaurants, and hotels were full before the beach season began in earnest, but many believe that the town would like to shed its associations with the Gypsies if possible, to raise its status as a beach destination.

Badone writes, “The Chaplaincy is caught in an ambivalent position between the need to provide its Romany clientele with the style of religious practice they seek, and the need to remain simultaneously within the guidelines of official Catholic teaching and practice.” 8 By the chaplains’ ongoing design and the Gens du Voyage’s continued commitment, the Gens are the most prominent pilgrims, both by virtue of the participatory roles they have, such as carrying the images of both the Saintes Maries and Ste. Sara, and by their number. The feast would be a much smaller, local event without them, as it is in October.

Many Gypsies and other Gens du Voyage believe it is important to distance themselves from gadjé, (in Manouche, gadzos), and see the church as a gadjé institution. Throughout their history in France and elsewhere in Europe — not only during their internment — Gens du Voyage have suffered discrimination, and likewise often keep a distance from other Europeans. Thus the chaplaincy works hard to put the Gens du Voyage front and center in the rituals.9

Anthropologist Patrick Williams, who has not written about the feast, but who studied Manouche (Mānuš, in their language) peoples intensively, offers another path for understanding that emphasizes appropriation and adaptation rather than competition. The universe in which the Mānuš travel, he reminds us, is, like the feast, markedly delimited by Gadzos: “The roads and paths they are traveling on have been built by Gadzos; the places where they are camping have been delimited by Gadzos… the fields and woods they are exploring have been fenced, planted and cultivated by Gadzos who guard them… But the Mānuš have the ability to appropriate all of this. Not as competitors… but in ways and modes specific to them and which the Gadzos do not understand.”10

Determining in depth what the pilgrimage means to Gens du Voyage proved unusually difficult.11 One reason is that, as indicated above, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer attracts a number of distinct communities of Gens du Voyage, each with their own cultural identity and history. These groups collaborate at times, but are not interchangeable. Further, more than once I was told by Gypsies I was introduced to, that if I wanted to understand the meaning of the feast, “Don’t ask questions. Just watch what we do.”

I was welcomed as a guest of the chaplaincy to social events in the various camp areas, but came up empty when I tried to discuss what anything meant. Williams claims that this silence is one of the most important characteristics of the Manouche community that he encountered, a response to living in the Gadzo world. By choosing silence, “[t]he essential is incorruptible, unassailable, it cannot be encroached.” A circle of silence protects what is most important in the world. Even paying attention may not be enough: “All the random gestures of everyday life appear as so many miscues aimed at those who would map the Mānuš way.”12

If Williams is right, then, the Gens du Voyage don’t come to be on display, to show their way to the world, or to raise their saint high for so that others will come to acknowledge her. Recognition by the Church would seem to be helpful, and perhaps prevents a full retreat from Catholic practice by the Gens du Voyage. Yet their motives shouldn't be presumed to be simply the same as everyone else's. “Another world exists within this world, and this other is the Mānuš domain.”13

One thing I can note is that for a surprising number of Gens du Voyage, the question of the truth behind who Sara was — Egyptian consort of Pontius Pilate, servant of the Saintes Maries, or local chief who welcomed the Saintes Maries — seemed to matter little to most of the people interviewed during this research. “Comme vous voulez” “As you wish,” several said, when asked about the correct story. "Who she is," in one sense, is hardly important. Who she is in some other senses is still apparently important enough to draw Gens du Voyage back year after year.

At the feast and beyond

For many of the Gens du Voyage, this week at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer is the primary, but not exclusive, point of contact with the Church. And for some, the feast at Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer is the occasion for sacraments like baptism and marriage, and for first communions. By most measures, chaplains say that the Gens du Voyages are like most other French Catholics in terms of their participation in Catholic ritual, which is to say that they receive sacraments of baptism and that the majority attend Mass infrequently. Marriage in Gens du Voyage families remains largely patterned in the fashion of their particular cultures, which is to say that it happens in stages. It begins with a traditional arrangement, whereby a couple announces their pairing and publicly moves in together. Only later, often with children or even adult children, is there a church ceremony.

Today perhaps half of the Gens du Voyage in France are Catholic, the other half having converted to Pentecostal Christianity, which is unusual in France. Pastors from the Gens du Voyage community have led this shift since the early 1950s. More recent Gens du Voyage immigrants from Eastern Europe tend to be Orthodox or Pentecostal.

For peoples whose history and identity have been defined by mobility, even if many of these “Gens du Voyage” tend today to actually live at fixed addresses, pilgrimage would seem to be the ideal religious form. Hence there are other significant Gens du Voyages pilgrimages to Lourdes, Mont Saint Michel, and to Ars, though Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer remains the largest. Badone, on the other hand, suggests that even for people who identify as travelers, Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer is “a stable center in a mobile world.”14 For most of the Gens du Voyage who do attend, pilgrimages like this are one of the few occasions when they do get to take their trailer a long distance and spend extended time away from their fixed location.15 They can meet family and friends whom they may not often see, while they celebrate Ste. Sara and the Saintes Maries.

- 1 Gens du Voyage are "traveling peoples." Elsewhere in the articles on Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, I use the term Gypsy generically for the Gens du Voyage, because that was the term preferred by most interviewees, if indeed they preferred any term at all. In this article, because of references to specific peoples such as Manouches, the term Gens du Voyage is used.

- 2For a commentary in French on the issues and complexities of naming among the Gens du Voyages, and the variety of cultures subordinated under that larger (and largely elite-defined) umbrella, see anthropologist Marc Bordigoni's Gitans, Tiganes, Roms: idées reçuessu le monde do Voyage (Paris, Le Cavalier Bleu: 2013), 17-24.

- 3Special thanks to Fr. Claude Dumas, a chaplain to the Gypsy community and the first Gypsy priest in France, for introductions, welcome and accompaniment in the camping communities. Interviewees were generous with their time thanks to his help.

- 4Eric Wiley, “Romani Performance and Heritage Tourism: The Pilgrimage of the Gypsies at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer,” The Drama Review, 49, 2, Summer 2005, 137.

- 5Wiley, 141.

- 6Wiley goes so far as to say, “Many villagers regard the Romani pilgrimage as an unwelcome invasion and occupation of their community despite the tourist business that it generates.” His list of problems includes “traffic, noise, crowding, garbage, unsanitary conditions” 137. He even cites another source (Peter Godwin, "Gypsies: The Outsiders” National Geographic 199, 4, 72-101) saying that in 2001, “‘an extra 200 riot police and a helicopter’ were reportedly stationed at the village for the pilgrimage.” Traffic was certainly an issue in 2017, but the latter issues were not apparent issues in 2017. Indeed, while the local officials met daily with chaplaincy officials in 2017, nothing about that seemed out of the ordinary for any event of this size and complexity.

- 7Ellen Badone, “Pilgrimage, Tourism and the da Vinci Code at Les-Saintes-Maries-De-La-Mer, France,” Culture and Religion, v. 9 no 1, March 2008, 31.

- 8Badone, 30.

- 9Badone, 29

- 10Patrick Williams, Gypsy Worlds: The Silence of the Living and the Voices of the Dead, trans. Catherine Tihanyi, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003, 29-30.

- 11Anthropologists might not be surprised that it would be difficult to achieve such understanding in a short research experience such as this. But conversations with an anthropologist who has spent considerable time with one Gens du Voyage group, and with other gadjé who have joined and volunteered at these pilgrimage events for years, indicated similar difficulty, even for people who deeply value the encounters.

- 12Williams, 75.

- 13Williams, 79.

- 14Badone 40.

- 15Williams, 61, notes that the same is true of attendance at Pentecostal conventions.