A person who went to Berlin relying only on eyesight for signs of Catholic life and faith — or any religion, for that matter — would find that other than through church architecture and decoration, religion is not to be seen very much. To see a layperson wearing a cross or other religious jewelry is a bit of a surprise, even at church, and religiously garbed nuns and clergy are a rare sight in public.

Yet architecture communicates a lot, and Berlin is a city that over the centuries has prized architecture as a medium of culture and expression. Berlin's architecture is decidedly a mixed bag, but Berliners have tried in the past and in recent years to build its identity through bold architectural statements. The classical imperial architectural legacy that once defined the city survives in only in bits and pieces. An occasional classical limestone building is often surrounded by modern office buildings and apartments. Albert Speer's vision is a remnant of the past. Indeed, while Berlin has preserved some great pieces of its imperial past, there is very little significant postwar architecture that nostalgically reinvents a classical ideal of the past.1 Architectural Modernism, born in large part in 1930s Berlin, has been a way of building anew and dealing with a past that had once described modernism as decadent and un-German.

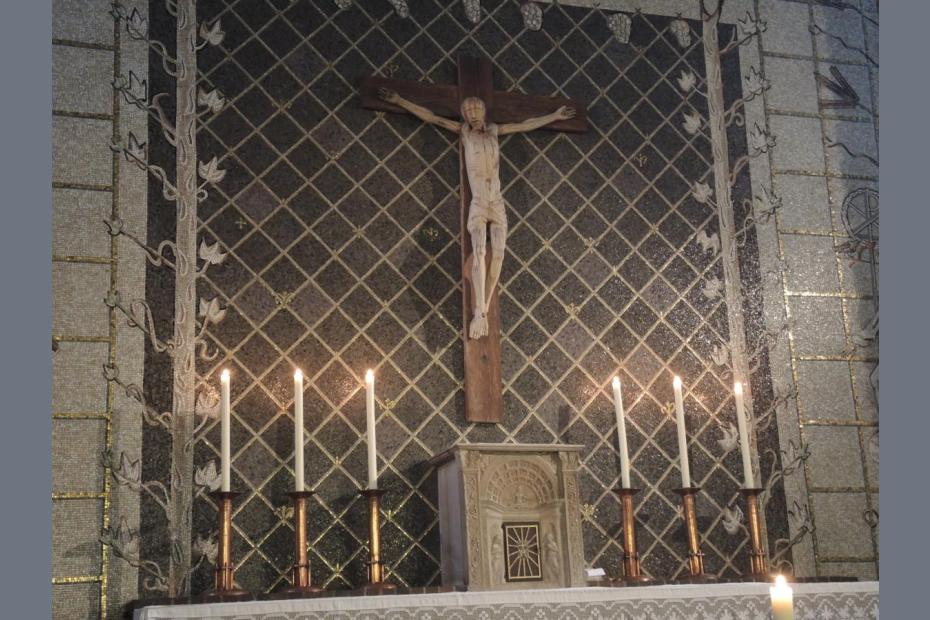

Berlin's Catholic church architecture, and the "look" of Berlin Catholicism, reflects this legacy. Many of its older churches, rebuilt after the war, include elements of modern design in Gothic or Romanesque revival spaces. In West Berlin, Modernism came to dominate, even before Vatican II. In the former East Berlin, churches were rebuilt in less elegant modern styles, on very tight budgets.

Berlin’s Cathedral, Saint Ansgar's, dates to the height of imperial classical architecture in the city, and was modeled after the Pantheon. The interior, rebuilt after the war on the East German side of the wall, is modern, and not highly adorned. Berlin’s 19th and early 20th century churches were generally built in brick or stone Gothic or Romanesque revival styles. But experimentation with new architecture began by the 1920s, with Art Deco, Expressionist, and modernist styles.

More than in many cities, Berlin Catholics have used new architecture as a way of signaling a forward-thinking church, open to modernity. Maria Regina Martyrum (dedicated 1963), built near the site of Plotzensee, a prison where resistors were executed in the Nazi era, is a decidedly modernist building. St. Canisius, in the Charlottenberg neighborhood, is one of the newest churches rebuilt after a 1995 fire destroyed the prior, 1950s modern church, is the latest church to be built in a modernist style.

- 1Peter Schneider writes of the process after 1990 that led to Berlin's newer architecture, "debates about the city's future all too often took the form of political exorcisms." "Clash of the Architects," in Berlin Now trans. Sophie Schlondorff (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux: 2014) p. 18.