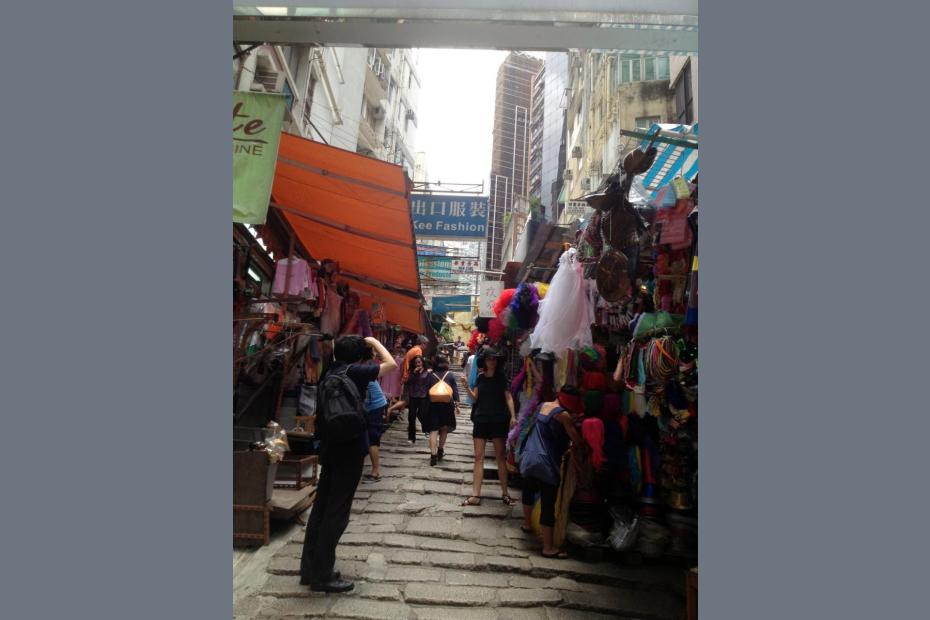

Hong Kong, a British colony until 1997, is a mixing place of Western (primarily British) and Chinese cultures. Hong Kong is a highly modernized, very densely populated global banking and business center, and also a place with glimpses of peasant culture in alley shops and stalls. Chinese will sometimes say that old Hong Kong culture is a legacy from rough and tumble seafaring and port life, but Hong Kong is also a global crossroads. Cantonese, the local Chinese dialect, is the dominant language, but English is tremendously important as well, as it has been for a century. Locals describe how British the city is compared to mainland Chinese cities and compared to nearby Macao, which was once a Portuguese colony.

Hong Kong is part of China since 1997, though it has a special autonomous status and its own passport controls under a "one country, two systems" agreement. The city was born and grew as a port for Western trade with China, and still serves in that capacity, even as direct trade has grown enormously. Business acumen is especially valued and celebrated, and local culture particularly values hard work, education, and capitalist free trade. Hong Kong is a place of tremendous wealth and income inequality, though it does have a reasonable social safety net. Cantonese Chinese, including Hong Kongers, are often said to be more brash than northern Chinese, and more focused on business, but values of harmony and preserving "face" -- honor or dignity in social situations -- are also topics of frequent concern in social interactions.

Definitive numbers on religious membership and degree of practice are difficult to pin down in Hong Kong, since practice and boundaries are extremely fluid and hard to categorize. Pew Forum surveys estimate that 56% of Hong Kong Chinese individuals are not affiliated with a religion,1 and by many measures, Hong Kong mostly appears to be an extremely secular society. But Hong Kong Chinese typically feel no need to formally regard themselves as “members” of any religious tradition. They feel free to participate in any of several Chinese religious traditions as needed, without belonging to one.

Some scholars describe practice simply as “local religion,” a mélange of Taoist, Buddhist and local religious practices. These practices include temple festivals to celebrate deities’ birthdays, intercession to patron deities to solve problems or invite fortune, fengshui and ancestor devotion.2 The natural world and the physical landscape are believed to be populated by spirits who must be respected and who can intervene for good or evil, and who have different specialized roles. “The pantheon of local religion is an ‘open’ system. New deities are introduced and others are ignored, forgotten and finally disappear from people’s view.”3

The leadership of these local religious movements is not regionally organized, but many forms of worship are still led by Taoist and Buddhist priests and nuns from one of many temples in the territory. At a temple, “Worshipers kneel, offer incense, food and paper products to the deity.”4 One also can find small shrines in apartments and incense burning at the door at small shops. Beliefs in lucky (and unlucky) numbers and auspicious times in the calendar also endure in Hong Kong Chinese culture, even among those who are not seemingly otherwise religious. 5

Protestantism is the historic and still dominant form of Western, Christian religious practice in Hong Kong (under the British, Anglicanism was the established Church of Hong Kong), though today Catholics are not far behind compared to the total number of Protestants.

To date, most of the Catholics & Cultures site for Hong Kong focuses on the experience of Filipina Catholics, who also provide cross-cultural insight into the character of Hong Kong Chinese life and Catholicism. Filipino clergy emphasize that whereas their own practice is more devotional and ritually-focused, Chinese Catholics tend to be far more doctrinally concerned. Chinese Catholics, they say, tend to be concerned with the logic of Catholicism and with doctrinal orthodoxy rather than with devotions. An unusually high number of Chinese Catholics are converts. In 2011, there were 1,121 children under age 1 baptized, compared to 3,156 persons over 7 years old and 9,013 catechumens (5,087 children, 1,415 men, 2,511 women). 6 In light of that, more Hong Kong Chinese Catholics received their faith formation in formal educational settings than through devotional practice.

Hong Kong has a high ratio of clergy and women religious to lay people. The church is headed by a Hong Kong Chinese bishop, and all but one of the diocesan clergy are Chinese. Most of the religious order priests are foreign. Chinese sisters outnumber Chinese priests by almost 3 to 1.7 In contrast to the mainland, the church in Hong Kong has been free to appoint its own leadership and to educate its clergy and religious without government involvement. In a city that highly values education, the Catholic church has especially made its mark through a large and string network of Catholic schools, so coveted by Hong Kongers that there is always talk and fear of parents becoming Catholic just to insure their children a place in those schools. The church has a significant institutional presence in the city in education and healthcare, serving predominantly non-Catholic students and patients.

In the years since the articles on this site were originally published, the political landscape of Hong Kong has changed, though it had already changed insuring the handover from British to Chinese rule, and in the intervening years.8 The mainland Chinese government has become much less tolerant of dissent and free speech, and many in Hong Kong fear that the freewheeling, open culture that had defined Hong Kong is a thing of the past. Dissidents have been arrested in large numbers and in May 2022 even 90-year-old Cardinal Zen, an outspoken critic of many Chinese policies, was arrested and held briefly for alleged “collusion with foreign forces” for having provided support to people arrested in prior political protests.9

- 1 Pew Research Center, "The Global Religious Landscape," Pew Research: Religion & Public Life Project, accessed August 29, 2013, http://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/.

- 2Tik-sang Liu, "A Nameless But Active Religion: An Anthropologist's View Of Local Religion In Hong Kong And Macau," The China Quarterly 174 (2003): 373-394.

- 3Liu, "A Nameless But Active Religion," 377-378.

- 4 Liu, "A Nameless But Active Religion," 377.

- 5 Liu, "A Nameless But Active Religion," 388-390.

- 6 Hong Kong Catholic Social Communications Office, "Statistics of the Diocese of Hong Kong - Catholic Diocese of Hong Kong," Statistics of the Diocese of Hong Kong As On August 31, 2011, accessed August 29, 2013, http://www.catholic.org.hk/v2/en/cdhk/a08statistics.html.

- 7 Hong Kong Catholic Social Communications Office . "Statistics of the Diocese of Hong Kong," http://www.catholic.org.hk/v2/en/cdhk/a08statistics.html.

- 8For an in-depth account of church-state relations in Hong Kong through 2015 see Beatrice Leung, "The Catholic Church in Post-1997 Hong Kong: Dilemma in church-State Relations" in Stephen Uhalley, Jr. and Xiaoxin Wu, eds., China and Christianity: Burdened Past, Hopeful Future (Armonk and London: M.E. Sharpe, 2001), 301-319.

- 9 For a fuller account see https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/16/arrest-of-cardinal-zen-sends-chill-through-hong-kongs-catholic-community