Israel was created and shaped by immigration. Until the 20th century, Jews constituted a small minority of the population of a sparsely populated Palestine. Successive waves of aliyah, Jewish migration from diasporas in Europe, the Middle East, the United States, and other parts of the world made Israel what it is today. The Hebrew-speaking Catholic community is an immigrant community as well, so it may seem strange to devote a special section that separates out the migrant/refugee communities as distinct from the Hebrew-speaking communities.

In the 1990s Israeli law was altered to allow “foreign workers” to work temporarily in Israel to fill a need for nurses, health care aides, farmworkers, hotel staffers and construction workers. Among these were large numbers of Catholics — particularly Filipinos, but also Indians and Sri Lankans. Since that time, a sizable number of refugees, including Catholics from Eritrea and other parts of Africa, have also crossed the desert and sought refuge in Israel, but still have no legal status there.

According to the pastoral workers who work with Catholic migrants and refugees, there are probably 50,000 Catholic foreign workers, a large proportion of whom are Filipinas. The migrant and refugee situation in Israel merits much more exploration, given its own complexities, but a few things about them can be noted at this point.

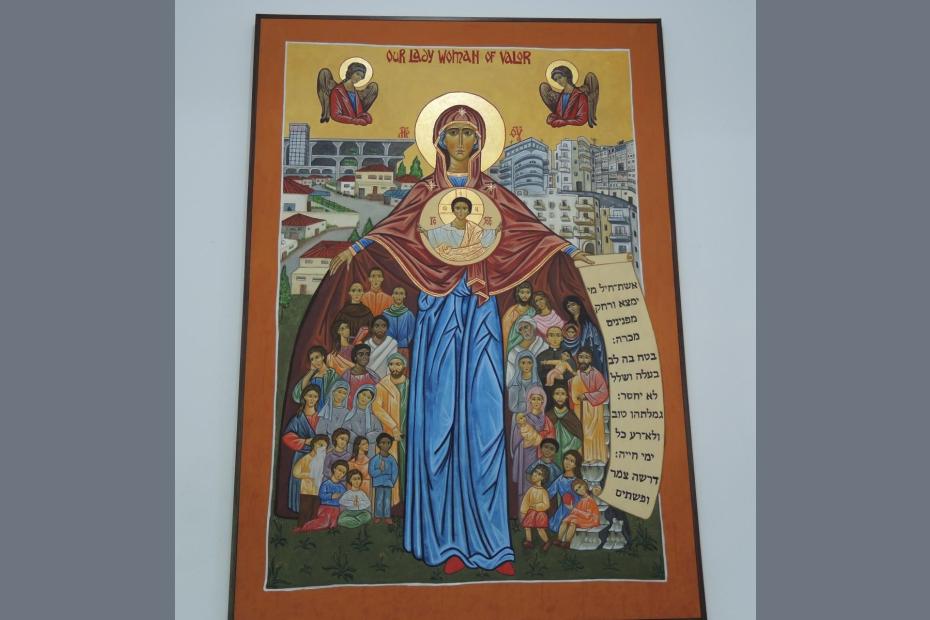

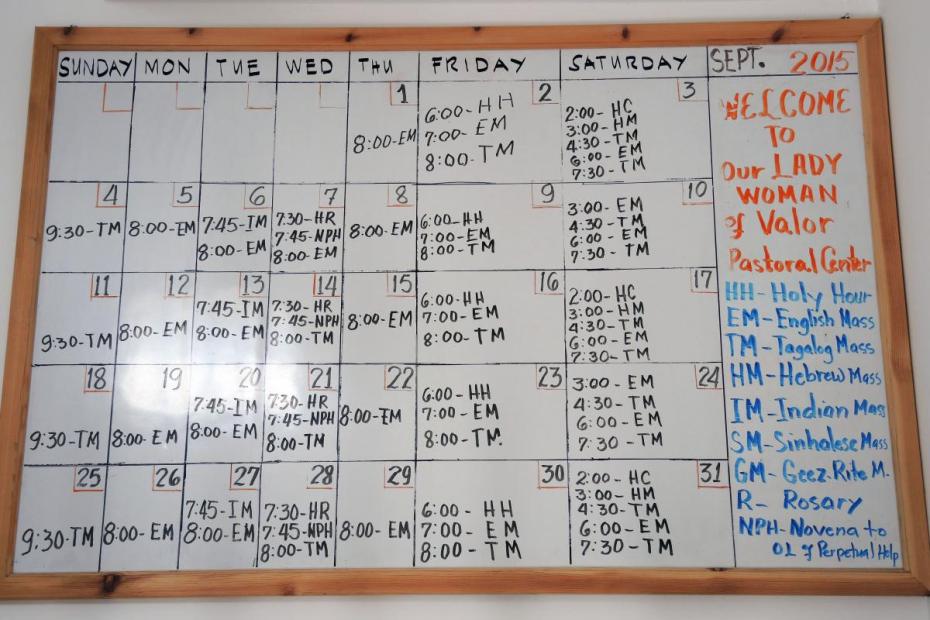

Catholic migrant and refugee communities gather and pray all over the country. There are more than 70 Masses a week in 11 languages for the migrant and refugee communities throughout Israel. The largest site for gathering Catholic refugee communities is Our Lady Woman of Valor, a pastoral center near the main bus station in Tel Aviv. The center, in a somewhat marginal area populated by immigrants and refugees, doesn’t look like a church, but more like a compound that could be an apartment house or some anonymous enterprise. It is a busy place that functions for many purposes — as a daycare site, catechism center, drop-in site, church, and social service center. Masses are held there throughout the week, because weekdays are often the only day off for home health care workers and other migrants.

Two things distinguish the migrant and refugee communities from the Hebrew-speaking communities. The first is that by virtue of current law, the vast majority of these believers have only temporary legal status and can never become citizens, nor can their children. Second is that unlike members of the Hebrew-speaking community, they did not come with Jewish family members or with a desire to inculturate their religious practice into a Jewish-Israeli context. Filipino adults, for example, typically want to continue to preserve whatever is possible of the Filipino religious practices and worldview they brought with them, and they favor communities that reflect that. They see themselves as Filipinos in Israel, more than as Filipino-Israelis. But while the parents prefer to pray in their native languages, their children attend school in Hebrew, often learning only to speak Hebrew with any fluency. Catechism lessons and Masses for all Filipino children are in Hebrew. In some sense, while most of the children lack long-term Israeli legal resident status, the children really are Filipino-Israelis, perhaps even more prepared for life in Israel than in the Philippines. The majority of guest workers come here alone, which brings many challenges as they work apart from their families. A small number of Filipinas do marry Israelis, thus giving the opportunity for legal status to their children.

Read more

Sara Toth Stub, "Christianity in the Holy Land Has Gotten a Big Boost from Migrant Workers," The Tower Magazine, no. 44, November 2016, http://www.thetower.org/article/strangers-in-a-strange-land-christian-migrants-are-changing-how-israel-prays-and-works/.

Ruth Margalit, "Israel’s Invisible Filipino Work Force," New York Times Magazine, May 3, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/03/magazine/israels-invisible-filipino-work-force.html.