In Camaiore, a small city in Tuscany nestled between mountains and the sea, one of the highlights of the year is the feast of Corpus Domini, when townspeople come out to make and view brightly colored sawdust tappeti, or carpets, and to participate in the religious procession whose route they are built to decorate. The carpets, which use new designs each year, are built on the Saturday night before the feast, often late into the night, and last only until the end of the Corpus Domini procession the following morning. Running the length of the old city, they serve as an adornment for Sunday morning’s Eucharistic procession, a manifestation of civic pride, and a catechetical device. The feast has become such a hallmark of the city’s identity that the local government is petitioning to have them recognized on UNESCO’s list of intangible cultural heritage.1

The feast of Corpus Domini, the Body of the Lord, also known as Corpus Christi in many parts of the world, is an occasion for devotion to the belief in the real presence of Christ in the consecrated host. The origins of the feast are in Liège, Belgium, in the 13th century. It is held in the last days of May or the first days of June, depending on the date of Easter that year.

The feast features a procession that follows Mass, often into the streets or around a public square. Examples of the procession in Italy can be found in Venice and St. Paul outside the walls (see video) in Rome. Camaiore’s celebration is distinctive for the sawdust carpets that line the road for much of the processional route.

Camaiore’s archives suggest that there were Corpus Domini processions there by the late 1400s, and local tradition claims that laying down small "carpets" of flowers for the Corpus Domini procession in Camaiore began in the first half of the 19th century. After 1930, colored sawdust became the material of choice, though in 2016, the Misericordes sicut pater, “Merciful like the father” image that symbolizes the Holy Year of Mercy, was still made primarily from flower petals. From the 1970s onward, the number and quality of designs have grown significantly. In 1968, a year of uprising and social consciousness in Italy and elsewhere, some carpets began to take on aspects of contemporary social concern.2

Planning and building

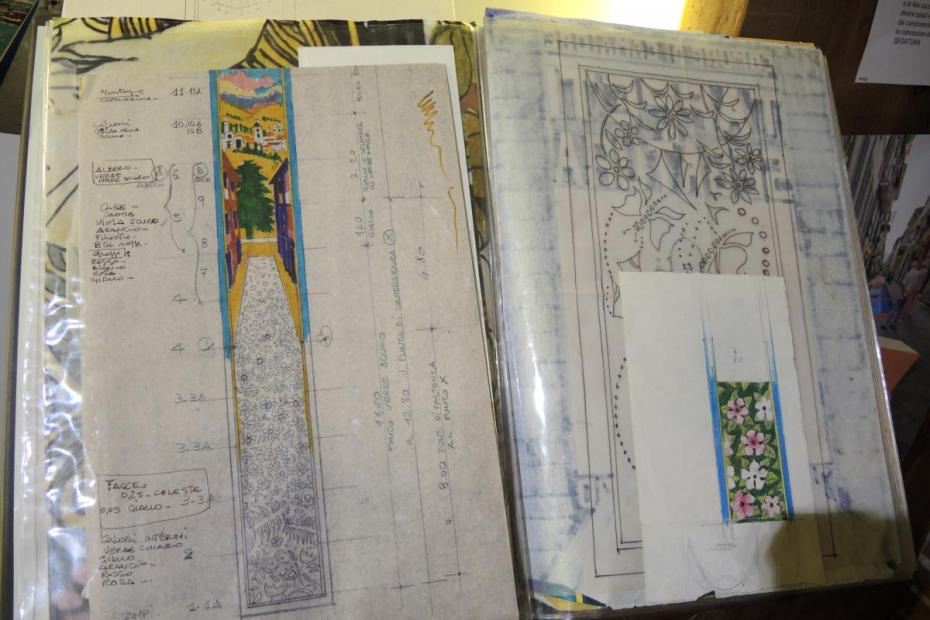

The work of designing the tappeti is a months-long process, which is amazing given that the results of such work are visible for such a very short time, only to be walked on and swept up hours after their completion.

The process begins with a conversation with the parish priest, who chooses a theme for the year, in consultation with the association of tappetari, the carpet makers and designers. For 2016, the theme was Mercy, for the Holy Year of Mercy. Each group had a work of mercy to design for, but did so independently, often in secret and in competition with each other. They spent months designing each carpet, handcrafting plywood stencils based on those designs, and coloring the sawdust. The varieties of wood and the fineness of the sawdust are specially chosen to ensure different textures and effects.

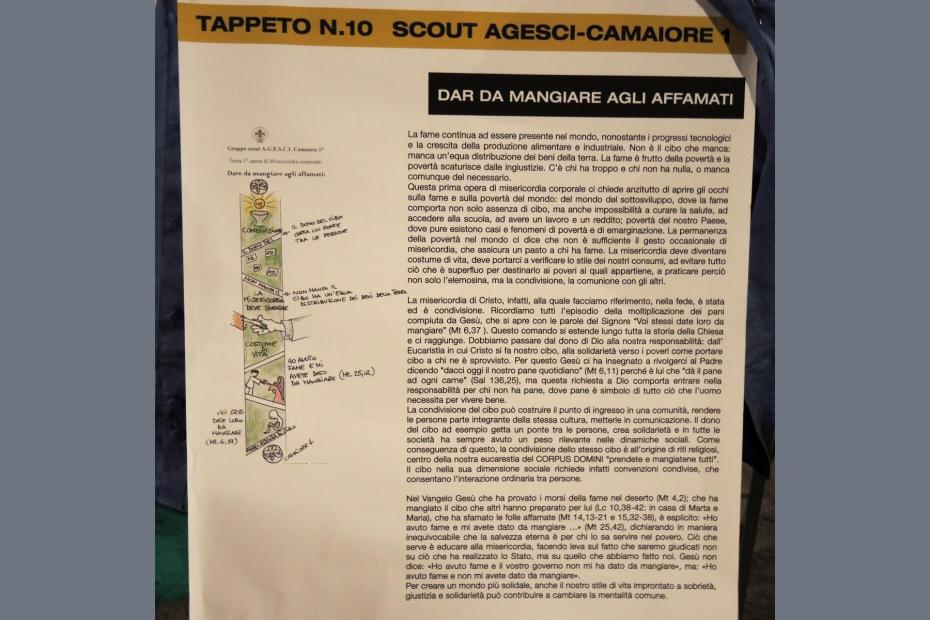

A few tappetari have become recognized masters of the form, cultivating a particular style and trying out new methods with support from many members of the group. Other groups involve the broader community in significant ways, such as by having prisoners or the infirm or schoolchildren contribute to the designs. One carpet is the work of local scouts, and two small but elaborate images at the foot of the procession, including the seal of the Holy Year of Mercy, are decorated in flowers and sawdust by local schoolchildren who are taught in school how to continue this tradition. According to townspeople, the tradition is passed down within certain families, but most of the current groups were apparently founded in the 1980s. Teams include people who are involved, by their own description, for religious purposes, and others who simply value the tradition. The La Torre group, founded by a circle of friends in the 1980s, cultivates an elaborate but very traditional style.3 C.RE.A. Cimbilium, a group that works with persons with disabilities, involves disabled people in the design of their carpet.4 Greenaway, which uses poetry and images resonant of graphic novels, often chooses some of the most controversial themes.5

Notte Bianca

Near sunset on Saturday evening before Corpus Domini, work begins in earnest. In 2016 there were 14 carpets up to 50 meters each. Each group has its space marked out and cordoned off, and line up large plywood stencils and bags of sawdust. Typically the colored sawdust is placed in boxes with screens on the bottom, and shaken like a sieve over the stencil, layer by layer. Some entail very complicated and highly layered processes to produce interesting shading and gradations.

For hours on the Notte Bianca, or White Night, townspeople observed the process throughout the night and chatted when possible with the tappetari. Some carpets were complete in a few hours, while others took most of the night. Unlike many town-wide outdoor feasts, Corpus Domini in Camaiore is not visibly commercial, and does not attract large crowds of out-of-town visitors, though the town is trying to draw more attention to the event. The town’s relatively few local restaurants and hotels benefit, but are not crowded, and there are no stalls selling food or souvenirs. Several apartments above the street hosted small parties for friends to visit to look down on the carpets and eat and drink. A parish priest and the mayor moved among the crowds, greeting people who clearly enjoyed seeing each other. The priest chatted with various groups and blessed them with holy water. During the evening, as the carpets were being built, a number of homes opened along the way. As the mayor and priest walked, almost everyone in attendance seemed to know them.

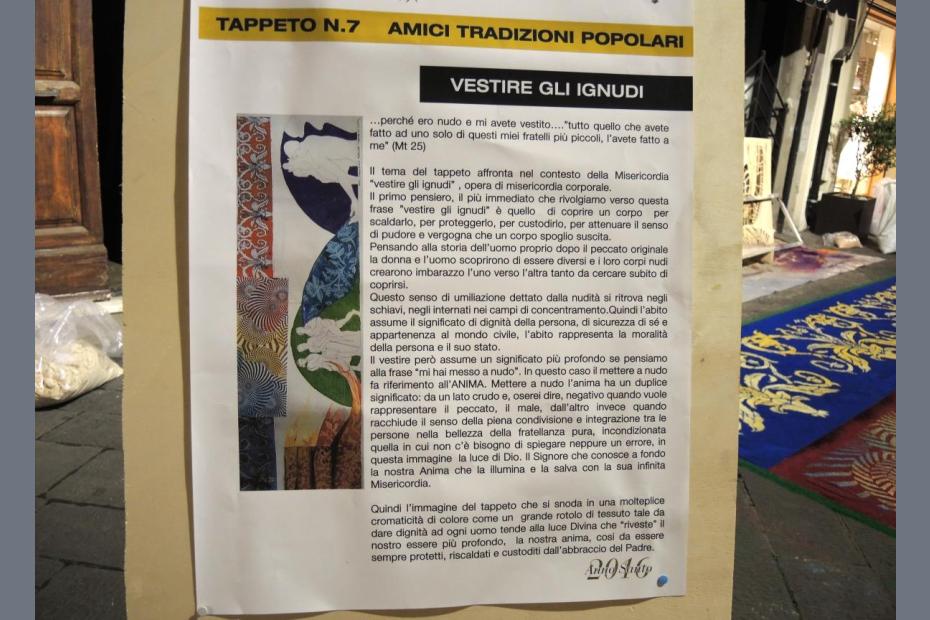

The carpets in 2016 were clearly organized around a catechetical purpose, with signs near many of them explaining each of the corporal works of mercy, such as feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, visiting those in prison, and burying the dead; and each of the spiritual works of mercy, such as bearing wrongs patiently and forgiving offenses willingly. Some carpets were quite traditional in the way they imitated real carpets and traditional Christian images. Others borrowed images from non-Catholic heroes like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr., or words from Emily Dickinson, or even used images of emaciated children or prisoners that were meant to jar the viewer.

Corpus Domini

Normally, the Mass for Corpus Domini is held outdoors, but in 2016 a steady rain kept it indoors. During the Mass, thunder and heavy rain lashed the town, soaking the tappeti. Crowds of townspeople filled the modestly-sized but elaborate church. Following Mass, the clergy, laity, lantern-bearers and others held a smaller procession with the monstrance through the crowded church. The planned procession, when the pastor walked on the tappeti under a brocaded baldachino (canopy) carrying the Eucharist in a large monstrance, with the mayor walking behind him, would have to wait another year.

Rain or shine, the city’s sanitation department arrives by mid-morning to sweep away the tappeti, the most elaborate of which have only been complete for five or six hours. City mayor Alessandro Del Dotto reports that there are many requests to leave the carpets in place longer, but the emphemerality of the carpets is one of the most important elements of the ritual itself.

Church, state, association

In many ways the event is a microcosm of Catholic life in Italy. A relatively small number of people take an active role in its execution, but many people have some cultural and familial stake in it, and it is part of the fabric of the town. Church, local government, and the association work together to organize the event. The pastor is responsible for choosing the overall theme. The city underwrites many of the costs of building of the carpets at a relatively modest price of about €19,000.

The mayor and others suggest that Camaiore is a bit more traditional than many other Italian towns, a matter less about political conservatism than about wanting to preserve a way of life and keep family at the center of things. Still, not all townspeople, by any means, are seriously religious or devout. But all can be involved. The mayor never encounters opposition to the public expenditure for the tappeti, which is seen as integral to what makes Camaiore, Camaiore. “Even the Communists are… working on this,” according to the mayor. “People are very proud. It gives a sense of what it feels [like] to belong to a community.”

- 1Special thanks to Prof. Andrea Borghini, Camaiore Mayor Alessandro Del Dotto, and Cristiano Bartelloni who made connections to make this entry possible.

- 2Avv. Alessandro Del Dotto et. al., eds., “The Sawdust Carpets,” Camaiore Town Council, 2015.

- 3“La Torre,” Tappeti di Segatura Camaiore, February 1, 2016, https://tappetidisegaturacamaiore.wordpress.com/2016/02/01/la-torre.

- 4“C.RE.A. Cimbilium,” Tappeti di Segatura Camaiore, January 16, 2016, https://tappetidisegaturacamaiore.wordpress.com/2016/01/16/c-re-a-cimbilium.

- 5“Greenaway,” Tappeti di Segatura Camaiore, June 13, 2016, https://tappetidisegaturacamaiore.wordpress.com/2016/06/13/greenaway. Information about many of the groups and images of past work are available at https://tappetidisegaturacamaiore.wordpress.com/gallery.