Lebanon, which straddles a 200 km strip of coastal cities, snow-capped mountains and agricultural valleys along the Eastern Mediterranean, is home to the largest concentration of Catholics in the Middle East, living among a larger population of Muslims. A multi-confessional state, Lebanon is home to 18 officially recognized religious groups, among them Sunni, Shīʿa, and small numbers of Alawite and Ismaili Muslims; Maronite, Greek Melkite, and modest numbers of Armenian, Chaldean, Syrian and “Latin” Catholics; Lebanese Greek, Armenian and Syriac Orthodox; and Druze communities living in a patchwork of villages, cities and neighborhoods often dominated by one of these groups. As one author summarizes it, “an area about the size of Connecticut or Northern Ireland… host[s] almost the entire religious diversity of the Arab world.”1

Among Catholics, the Maronite Church, which is centered in modern-day Lebanon and whose liturgy is rooted in Syriac ritual traditions, is by far the largest and most influential. Maronites have lived as Christians in a land that was, from AD 634 to 1918, except during the Crusades, ruled by Muslims. Historians consistently assert that it is only because of the Maronites that Lebanon came into being as an independent country distinct from Syria. The Greek Melkite Church, whose roots are in Northern Syria and whose traditions are Byzantine, is the second-largest Catholic church. The Roman, or Latin, Catholic Church is tiny, composed largely of expatriates. Though, as their names imply, the Syrian Catholic Church and the Armenian Catholic Church are originally rooted elsewhere, and though their members are relatively few in Lebanon, both have their patriarchates in Lebanon.2 Alongside the Maronite patriarchate, this means that three of the six patriarchs of the Catholic Church reside in Lebanon.3

There are officially almost no religious “nones” in Lebanon, not because all are believers, but because Lebanon has an unusual system that effectively requires religious affiliation under the aegis of some recognized Christian or Muslim leader. Religious identity is marked on national identity cards at birth. Marriage and other major life events are governed by the religious communities a person is born affiliated with.

Lebanese people speak a local form of Arabic, though a great deal of commercial life and education is in French or English. Maronite interviewees all said that they pray in Arabic, both formally and informally. The Maronite liturgy is in Arabic and Syriac, an ancient language of the region related to Aramaic, while the Melkite liturgy is in Arabic and Greek.4

The Maronite church in particular is a major institutional force in the country, sponsor of well-regarded schools and universities.

Historical background

Christianity in Lebanon is as old as Christianity itself. The northernmost territory of Galilee, the land of Jesus’ birth and preaching, is part of Lebanon today. According to the Gospel of Mark, people from the Lebanese coastal cities of Sidon and Tyre were among those who heard Jesus preach (Mark 3:7-8). Jesus healed a Canaanite woman there (Matthew 15:21-28). The Acts of the Apostles records a visit by St. Paul to an early Christian community in Tyre (Acts 21:2-6) and another to Sidon (Acts 27:3).

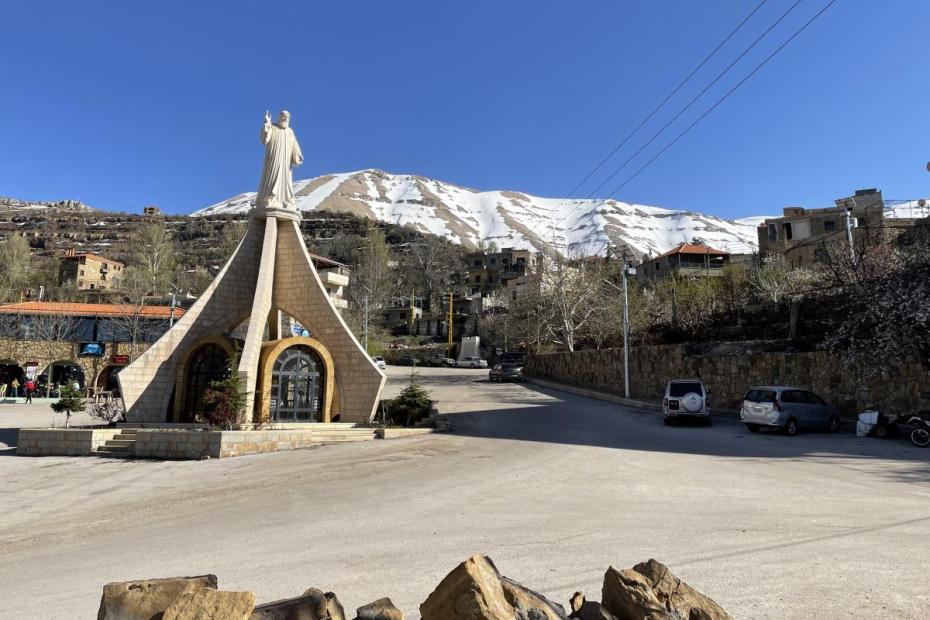

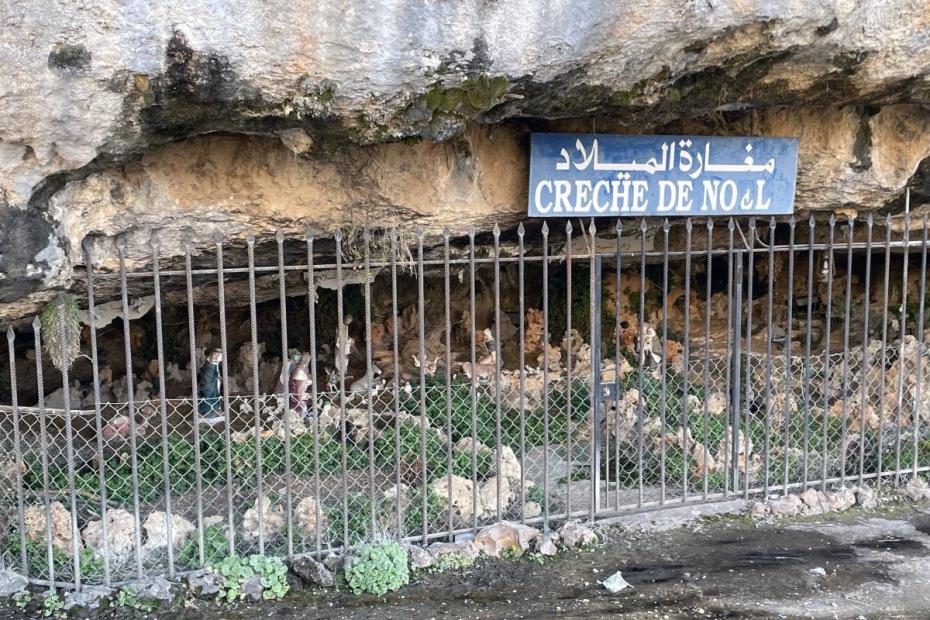

In the following centuries, under Roman-Byzantine rule, Christian shrines and churches spread up the Lebanese coastline and into the mountains and valleys. Not far north of modern-day Lebanon, the coastal city of Antioch, once one of the Roman Empire’s main cities, whose church is said to have been founded by St. Peter, developed into one of the five major centers of Christianity.5 Lebanon’s Maronite and the Greek Melkite churches both claim to be heirs to the Antiochene tradition, but are the products of distinct spiritual, theological and ritual traditions.6 The use of “Greek” in the name Greek Melkite derives from that Syrian church's links to Byzantium and its liturgies, which drew upon the splendor of Byzantium’s urban, imperial context.7 The Maronite tradition[link] arose in more rural, peasant contexts, in the Orontes Valley in present-day Syria and Turkey, among followers of a monk named Maron.8 After the mid-7th century AD, the monks and lay believers of the Maronite faith fled to the mountains and valleys of Mount Lebanon, sometimes finding refuge in caves in an area still known as the Wadi Qadisha, or “Holy Valley.” The impact of so many centuries of ascetic, monastic leadership in the Church made a deep imprint on Maronite spirituality, even though the majority of Maronite Catholic priests are married with families.

Muslim Arab armies conquered the region in the 7th century and brought Arabic as the common language, adopted even by those who remained Christian. In their attempt to reconquer the Christian Holy Lands and other parts of the Levant, Frankish Crusaders established coastal strongholds. Their presence occasioned the first formal ties between the Maronite church and the Roman church in 1180, and in 1215 the Maronite Patriarch attended the Lateran Council in Rome. Eventually, the Crusaders were ousted by Egypt’s Mamluk sultanate. Ottoman Muslim rulers replaced the Mamluk sultanate in the early 16th century. Maronites strengthened their ties to Rome during this period to lessen their isolation, and by 1515 Maronite-Roman union was fully realized. Rome provided religious legitimacy and support, but Maronites were pushed repeatedly to adjust to Roman theological orthodoxies and practices.9 In 1584 a Maronite college was established to educate priests in Rome.

The Greek Melkite Church developed as a Byzantine Orthodox tradition, not a Catholic one, for most of its history. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, a group of Orthodox bishops and believers in Aleppo switched to communion with Rome, establishing the Greek Melkite Church. Many of those believers came to Mount Lebanon to seek protection.

The Ottoman empire ruled minority Christians and other religious groups under a system “in which each minority, whether of a religious or national character, normally became a self-governing millet or ‘nation.’ Each of these Christian groups was ruled by a Patriarch or equivalent, and the bishops and clergy assumed civil duties.”10 That system provided a template for the modern Lebanese confessional political system.11

The project that created Lebanon as an independent country, distinct from Syria, was a fundamentally Maronite project.12 In 1860 Maronite peasants launched an uprising against feudal lords that ended in the massacre by the Druze lords of large numbers of Maronites. At Maronite request, coinciding with its own colonial ambitions, France intervened to end the conflict.13 With the French government paying scant attention to education, Catholic orders—French, Melkite and Maronite—developed and supervised a good deal of the educational infrastructure. With France’s help, the Maronites achieved special regional administrative status within the Ottoman empire for Mount Lebanon as an 80% Christian, 58% Maronite province, the core of what later expanded to become the Lebanese state.14 The war also marked the beginning of a shift of major Maronite and Jesuit educational institutions from the mountains southward, beyond territorial Mount Lebanon to the coastal city of Beirut.

After the breakup of the Ottoman empire at the end of World War I, France, under League of Nations authority, assumed a mandate over the territory that now comprises Lebanon and Syria.15 Maronite Patriarch Hoayek was a key player in the Versailles negotiations that led to the founding of Lebanon as a separate republic from Syria, first under French mandate in 1926, and then as an independent state in 1941.16 When Maronites achieved their political aim of independent statehood, the geographic area that they included, broader than the traditional Maronite strongholds of Mount Lebanon, knowingly resulted in significant dilution from their demographic majority status.17

Following the Armenian genocide of 1915, which decimated an ancient Christian community of more than 1.2 million people in what is now Turkey, a remnant community, many of them orphans, came to Lebanon. Though the number of Armenian Catholics in Lebanon is modest, Beirut subsequently became the patriarchal see of the Armenian Catholic Church.18 Syrian Catholics, who had joined with Rome from the Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church, established their patriarchate near Beirut in 1932.

After 1948 Lebanon absorbed a huge influx of Palestinian refugees who remain classified as refugees today, not Lebanese citizens, living in vast camps awaiting return to Palestine. Despite their separation, they have been a powerful factor in modern Lebanese history, and number up to 475,000 people.

Lebanon endured a brutal civil war from 1975 to 1990, fanned by local conflicts, the Arab-Israeli war, regional Syrian and Iranian power plays, and great power machinations. The era was marked by atrocities, massive uprooting of people into ethnic and religious enclaves, deadly infighting within religious groups that split into factions, and outward migration. Political parties formed their own militias, and party leaders became warlords. The churches were no less caught up in the factionalism, though the Patriarch tried to stay out of the political process and to serve instead as a moral voice.19 A huge number of Christians migrated from Lebanon, which continued to shift the religious balance of the country and enhanced the shift of the Maronite Church from a largely regional entity into a global one.20 The civil war deeply undermined the credibility of traditional political elites, but some observers claim that it elevated the place of the Maronite church as a moral and cultural voice.21

A fragile, yet in ways ossified, contemporary context

In the aftermath, Lebanon remains a visibly militarized country. Soldiers with machine guns guard the front of churches and mosques when services are in session, and there are occasional military checkpoints along roads. (At one checkpoint, in an interfaith, yet typically Lebanese form of greeting, a driver wished the soldier of unknown faith, in Arabic, “May God give you serenity.”) To add to the challenges facing Lebanon, the Syrian Civil War that began in 2011 sent an estimated 1.5 million refugees over the border into Lebanon, a massive influx into a country of 5 million people.22 Though cities are relatively mixed, many villages are primarily composed of members of a shared religious community.

Lebanese confidence in political leadership is low, and the institutionalized confessional system, which allocates political power to constitutionally recognized religious groups, is often partly held to blame, including for the negligence that led to the huge port blast that destroyed parts of Beirut in 2020. Some interviewees suggested that skepticism over the system was producing a kind of secularization, or distancing from the churches, among people they knew. In 2023, Lebanon is in a financial crisis, suffering one of the highest inflation rates in the world, following an intervention in the banking system that saw Lebanese people lose access to almost all of their savings.

Given disproportionate Christian out migration and comparative fertility rates between Muslims and Christians, the Christian majority is a thing of the past, but the confessional structure that links religion and politics endures, ordering many facets of life in Lebanon. The constitution ensures that a Maronite Catholic serves as president and commander of the armed forces and that Christians hold half the seats in parliament. Other recognized religious groups are ensured their own offices and proportion of seats.23 To protect a fragile balance of power, the constitution ensures that almost no one in Lebanon is religiously unaffiliated, no matter what their interior beliefs are. Citizens are assigned to a recognized confessional community at birth, on an identity card, normally according to the identity of the father. There is no civil marriage; a couple needs to be married under the authority of a religious community.24 The ability to divorce and often to inherit depends on the rules of that religious community.

Because of the political repercussions, the 1932 census is the last official census undertaken in Lebanon. Statistics about membership in any religious group in Lebanon should be approached with caution. As the Holy See counts it, the Catholic population in Lebanon includes about 1,580,000 Maronite Catholics, 425,000 Greek Melkite Catholics, 12,000 Armenian Catholics, 100,000 Syrian Catholics (up from 14,500 before the Syrian civil war), and 20,000 Chaldean Catholics (an increase from 10,000 as recently as 2005, as families fled Iraq).25

The confessional system has another impact on religious competition and the character of religious life. It crowds out Pentecostal churches and others like Jehovah’s Witnesses or Mormons, who lack official status for weddings and the like. Even mainline Protestants are represented collectively in the government, as a tiny minority. Charismatic forms of religiosity, so common in many other parts of the world, find no place here because churches do not encourage them and there is no influence by other churches’ missionaries who might import it as a competitor form of religiosity.

Whatever religious tensions the country may endure, those interviewed for this research said that they had much more in common culturally with Muslim and other Christian Lebanese than was distinctive. All Lebanese, interviewees insisted, essentially share a common local culture when it comes to food, language, and expectations about family life and manners.26

Yet the focus of religious life in Lebanon, interviewees suggested, still tends in a fundamental way to be tuned inwardly—not so much inwardly in terms of individual piety, but inwardly to the well-being of one’s own clan and community. The public positions and educational priorities of the Maronite Church in Lebanon, they said, were less focused on social doctrine of Roman Catholicism than on the wellbeing and history of that particular community.

- 1William W. Harris, Lebanon: A History, 600-2011, Studies in Middle Eastern History (Oxford University Press, 2012), 3.

- 2Until the 20th century, of course, there was no political distinction between Syria and Lebanon, so in one sense the distinction made here is an anachronism. The use of each label here is only meant to convey geography.

- 3The others are the Coptic Catholic Patriarch of Alexandria, the Chaldean Catholic Patriarch of Babylon and the Melkite Greek Catholic Church. The list excludes those whose Patriarchal titles are titular. Pope Benedict XVI renounced the title of "Patriarch of the West" in 2008, though Rome is historically a patriarchal see.

- 4For their instrumental support for on the ground research in Lebanon in 2013 and in 2022, the author thanks Fr. Dan Corrou, SJ, and Patrick Khoury. For his advice and feedback on historical matters, thanks are also due to Charles Al Hayek.

- 5The Patriarchs of the Maronite, Syrian Catholic, and Greek Catholic Churches of Lebanon are among the five claimants to the title of Patriarch of Antioch. That city, known today as Antakya, is in present-day Turkey.

- 6A third Christian tradition, the Jacobites, neither Orthodox nor Catholic, dates back just as far and endures in Lebanon today.

- 7Lebanon’s Greek Orthodox derive from the same tradition.

- 8The history of the Maronite church before the Middle Ages is murky and contested. Its surviving documented history before then is minimal, and was perhaps even destroyed because of theological claims judged to be unorthodox by Roman standards. See Harald Suermann, “Maronite Historiography and Ideology,” Journal of Eastern Christian Studies 54, no. 3-4 (2002): 129-148. The church’s position is that it was founded by followers of St. Maron and that another monk, St. John Maron, was its founder and its first patriarch in a line of succession from the church of Antioch.

- 9For a history of these first centuries of encounter, including Roman expectations of Maronite submission and adjustment to Roman liturgical and theological norms, see Kamal Salibi, “The Maronite Church in the Middle Ages and its Union with Rome,” Oriens Christianus XLII (1958): 92-104.

- 10Anthony O’Mahony, “Syriac Christianity in the Modern Middle East,” in The Cambridge History of Christianity, vol. 5, Eastern Christianity, ed. Michael Angold (Cambridge, March 2008), 515.

- 11The millet system did not carry over into the modern age in the rest of the former Ottoman empire.

- 12This is not to deny that there was a range of interests driving the state’s creation, but Maronite interests are generally understood to have been at the forefront. For accounts of the interplay of sectarian, social and economic interests at play, see Harris, Lebanon: A History, 5, 147-159 and Kamal Salibi, A House of Many Mansions, The History of Lebanon Reconsidered (Berkeley, University of California, 1988), 26.

- 13For an extended examination of the complexities and implications of this conflict, see Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon (Berkeley: University of California, 2000). Boutros Labaki similarly defines the conflict primarily as an economic one. Boutros Labaki, “The Christian Communities and the Economic and Social Situation in Lebanon,” in Christian Communities in the Arab Middle East: The Challenge of the Future, ed. Andrea Pacini (Oxford: Clarendon, 1998), 235-236.

- 14Harris, Lebanon: A History, 148.

- 15The British and French worked out an arrangement in 1915-16, the Sykes-Picot agreement, that gave parts of the Ottoman empire to each imperial power, imagining Syria as an Arab state and an expanded Mount Lebanon, ruled from Beirut, as a separate state, which is what the Maronites wanted. Harris, Lebanon: A History, 172-3.

- 16Harris goes so far as to claim, “If any single person had a claim to be the founder of Greater Lebanon, it was Patriarch al-Huwayyik [Hoayek]... The Maronites were the community without which the state would not have existed.” Harris, Lebanon: A History, 184. Other ethnic communities like the Shiites joined out of a sense that it was in their own best interest. Harris, Lebanon: A History, 193.

- 17A deadly famine in the mountain region in 1916 made the Maronites resolved to include the fertile but largely non-Christian Bekaa valley. French and British interests drove the inclusion of areas south of Beirut. Harris, Lebanon: A History, 176-9. Political power was then divided on the basis of a 1932 census that showed Maronites as 51% of the population. Because of the political implications that a new census would entail, it is the last official census ever taken.

- 18S. Peter Cowe, “Church and Diaspora: The Case of the Armenians,” in The Cambridge History of Christianity, vol. 5, Eastern Christianity, ed. Michael Angold (Cambridge, March 200), 450-451.

- 19Fiona McCallum, “The Maronites in Lebanon: An Historical and Political Perspective,” in Eastern Christianity in the Modern Middle East, eds. Anthony O’Mahony and Emma Loosely (Abingdon, Routledge, 2010), 34.

- 20Labaki (“The Christian Communities,” 226-229) counts 670,000 Christians and 157,000 Muslims as medium and long-term refugees from this period. Elsewhere in the same article, he counts more than a million emigrants from Lebanon between 1979 and 1994.

- 21McCallum, “The Maronites in Lebanon,” 37. A 2001 survey of Maronites by Simon Haddad showed that 53.1% of Maronites favored making Lebanon a secular, non-confessional state, and 39.8% opposed, but Lebanese Maronites I spoke to suggested that this was unlikely to happen, much as they might prefer it, because it would undermine entrenched power interests. Simon Haddad, “A Survey of Maronite Christian Social-Political Attitudes in Postwar Lebanon,” in Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 12, no. 4 (2001): 474.

- 22Government of Lebanon and the United Nations, “Lebanon Crisis Response Plan,” February 2021, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/LCRP_2021FINAL_v1.pdf.

- 23For an accessible, online assessment of the political and social implications of the confessional system, see Alexander D. M. Henley, “Religious Authority and Sectarianism in Lebanon,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, accessed May 7, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/12/16/religious-authority-and-sectarianism-in-lebanon-pub-66487. The social historian Leila Fawaz regards the system as a source of stability, the civil war notwithstanding. Leila Fawaz, “Understanding Lebanon,” The American Scholar 54, no. 3 (Summer 1985): 377-384.

- 24It is possible to marry abroad in a civil service and to have that marriage recognized in Lebanon, but this is rare.

- 25The Annuario Pontificio’s statistics on the dioceses of the Eastern Churches have been compiled by Ronald G. Roberson, CSP for various years from 1990-2013 and are available at http://www.cnewa.org/source-images/Roberson-eastcath-statistics/eastcatholic-stat13.pdf.

- 26Leila Fawaz makes this point about the founding of the Republic: “basic social mores and values” shared across confessions paved the way for unity. Fawaz, “Understanding Lebanon,” 378.