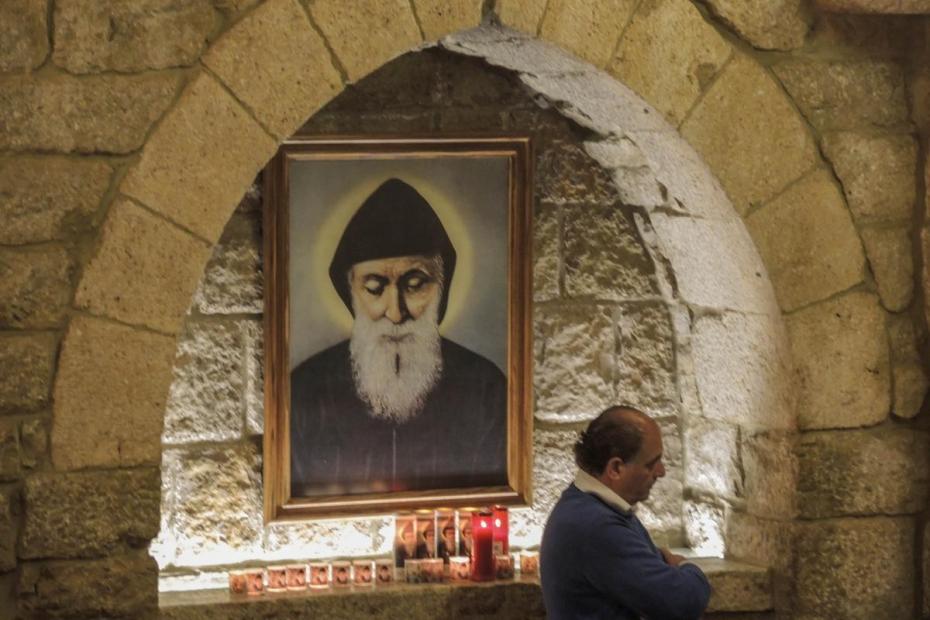

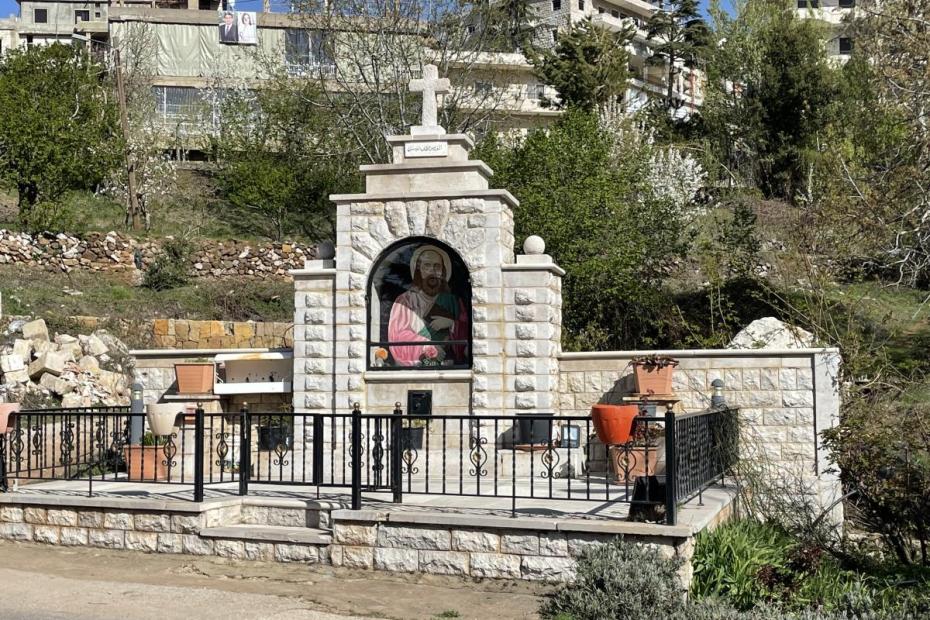

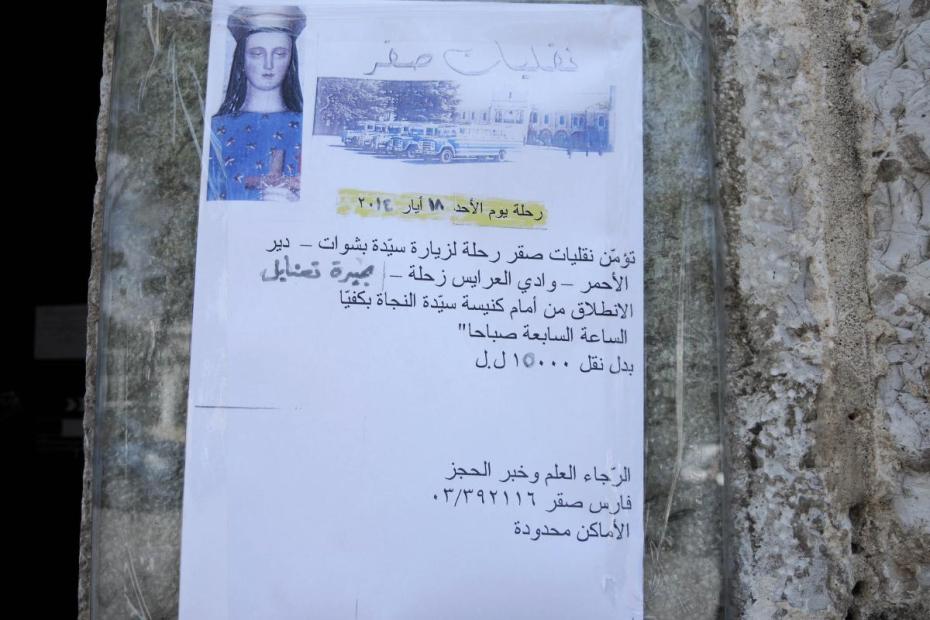

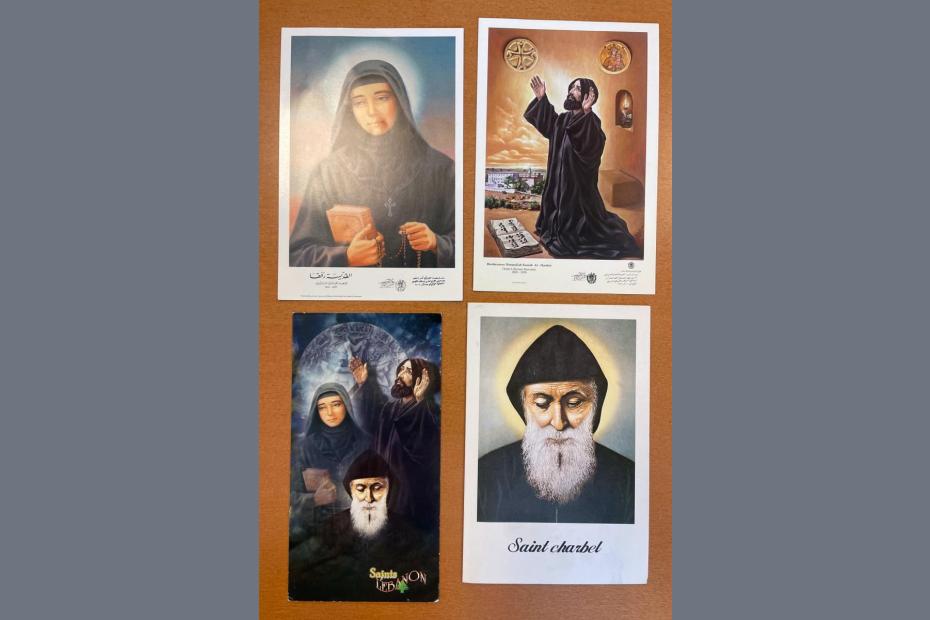

Images of saints are ubiquitous along streets, in public squares, and in homes in Maronite parts of Lebanon. A visitor who had no knowledge of Catholicism might conclude from the images he sees in public that the Virgin Mary in particular, followed by two natives of Lebanon, St. Charbel and St. Rafqa; and St. Elijah (Ilyas) are the key figures of the Catholic faith. Another Lebanese saint, Nimatullah Al-Hardini, is also prominent on holy cards, often featured together with Saint Charbel and Saint Rafqa. By one count, there are more than 900 places in Lebanon dedicated to the Virgin Mary.1 These images obviously do not tell all of the story—one readily finds churches and monasteries named in honor of St. George, St. Michael, St. Joseph and others, and the liturgy focuses on the life and sacrifice of Jesus—but they do point to some important characteristics of Maronite Catholic spirituality in Lebanon.2

A procession welcomes the arrival of relics of St. Rafqa, a popular Lebanese saint thought to have miraculous powers.

The on-the-ground research that informs this and other Lebanon articles on the Catholics and Cultures site focuses especially on Maronites, the largest Christian community in Lebanon.3 Nancy Jabbra’s published research among Greek Melkites in the Bekaa Valley offers added insight. Both sources make clear that while the Lebanese Maronite and Melkite Churches have distinctive devotional ways of practice, the boundaries are permeable: saints from Latin traditions have been imported into Maronite devotion, and Maronite devotions have found their way into Melkite life.

Devotion to saints can provide particular insight into the most important values of local religious culture. Saints could be chosen primarily because they serve as protectors, role models for Christian service, miracle workers, or patrons of local identity, among other things. In recent decades the Maronite Church has refocused attention from European to Lebanese-born saints, but the admired qualities of the Maronite and European saints remain relatively consistent. All stand out in particular for their intense asceticism, and also for miracles associated with them. They are not, for example, known for forms of service they provided in the world, or for missionary work. Miraculous powers, as we shall see, are at the heart of devotees’ attraction to saints in Lebanon. Saints’ power to protect families from harm also surfaces as a second key cause for devotion.

The most prominent Lebanese saints will be unfamiliar to most readers from elsewhere, though the first three are canonized by the Roman Church ostensibly for devotion by all Catholics:

- St. Charbel (or Sharbel) (1828-1898, canonized 1977) was a hermit monk known for miracles ascribed to him after his death. Given that he was a hermit, little is known about his actions, and he left no writings. He never spoke, even to his mother when she visited. Rather, the radical austerity of his life, and miracles said to have occurred after his death make him integral to contemporary devotional life. Charbel’s birthplace and the cell where he died draw a consistent stream of pilgrims. Charbel is always portrayed as he is said to have lived, eyes downcast.

- St. Rafqa (or Rafka) (1832-1914, canonized 2001) was a Maronite nun known for the way that she endured (and perhaps prayed for the gift of) intense physical suffering and remained dedicated to prayer. She is said to have miraculous powers as well.

- St. Nimatullah al-Hardini (1808-1858, canonized 2004) was a mentor to St. Charbel, an ascetic, and is known for many miracles attributed to him after his death.

- St. Ilyas (Elijah) stands out because he is venerated in the Latin Church as a prophet of the Hebrew Bible, not a saint. In Lebanon, he is often pictured with his sword raised above his head, signaling his role as a protector.

Two European saints from the Latin Catholic tradition, Thérèse of Lisieux and Saint Rita of Cascia have significant followings among Maronite Catholics in Lebanon, though they have been somewhat displaced by the native saints today. Thérèse, the 19th-century cloistered Carmelite nun is known for her suffering and early death and for her emphasis on her own insignificance, a spirituality known as the “little way.” Saint Rita of Cascia, a medieval Italian married woman turned cloistered nun, is also known for her embrace of intense suffering. She is the patroness of impossible cases and difficult marriages.

Devotion to Thérèse and Rita owes a great deal to the European links forged by 19th- and early 20th-century missionaries. At the same time, one has to ask why devotion to these saints prospered out of the panoply of European saints who could have drawn people’s devotion. That they all endured suffering as their route to holiness links them all.

Devotion to the three Maronite saints puts monastic spirituality—indeed, the most extremely ascetic versions of it—at the cultural forefront. None of them was lay or lived in the ordinary world. As I talked to Maronite Catholics, a paradox emerged: Lebanese lay Maronite people seem, particularly in cities, to be people who know and appreciate luxury. Interviewees confirmed this as a cultural trait. Yet the saints they admire, like Charbel, lived lives of quite extreme monastic asceticism.

Posed with that dilemma, and asked if people were drawn to the saints in some hard-to-perceive way as role models, one young man, “Robert,” who was devoted to Charbel and had an image of St. Charbel in his bedroom, laughed and responded, “No one wants to live like Charbel. They want miracles. And Charbel delivers miracles. People want to live like the elites.” Several women who were part of a group conversation after that agreed, noting that too often women at church want to show off their best clothes and drive in the best cars. Yet they were devoted to Rafka and Charbel. Robert’s and the women’s comments did not presume to judge this as hypocritical but simply acknowledged that it is the way things are. Historically there are plenty of examples of ascetic lay devotion, but in contemporary Lebanon, it now seems to be a thing of the past.

Marian devotion

The biggest shrines in Lebanon, and many small ones in the streets, are devoted to Mary. Though she is understood differently by each group, devotion to Mary unites Muslims and Christians. They will often be found mixed in together at Marian shrines. May and August remain particular times of devotion to her. The feasts of the Annunciation and of the Assumption are national holidays. Her image is visible in many small shrines in Mount Lebanon and in Christian neighborhoods of Beirut.

Saydet Loubnan, Our Lady of Lebanon Shrine, the largest Christian site in Lebanon, may be the primary site for noticing the depth of devotion to Mary. It was completely rebuilt after the civil war on the crest of a mountain far above the Bay of Joumieh. During one Friday afternoon/evening visit, crowds made their way up the mountain to spend time there and to pray.

Watch a drone video of Our Lady of Lebanon at Harissa Park.

Watch a drone video of Our Lady of Lebanon at Harissa Park.

Another site, Our Lady of Béchouate, a church in a small Maronite village in a primarily Shiite region in the northern Bekaa Valley, became regionally famous following a purported 2004 apparition to a visiting Jordanian Sunni Muslim boy. Since then, Christian and Muslim visitors have flocked there and the infrastructure of the shrine has been built up significantly by Church and public officials alike.4 Emma Aubin-Boltanski, who has written about the site and its visitors, describes the Virgin as a “protectress” of the local people through a variety of difficult times, which is the essence of her miraculous power. Second, she is regarded as a mediator between Maronite and Shiite neighbors.5

A last note on Maronite saintly devotion: though his feast day is a holiday and Maronite holy day of obligation, St. Maron, the saint around whose practice the Maronite Christian community first formed, was not described by any of the lay people interviewed as a “go to” saint; nor was St. John Maron, the first patriarch of the Church. Neither were they visible in houses or along roadsides.

Greek Melkite Saints

Nancy Jabbra’s accounts of Greek Melkite Catholic life in a village in the Bekaa valley shed light on a number of local practices.6 Images of saints are ubiquitous in homes throughout the village. The most prominent saints are St. Mary, St. Elijah (Ilyas), St. George, St. Michael, St. Joseph, St. Barbara and St. John the Baptist. Some are not necessarily Greek Melkite-associated, but Roman (Italy’s St. Rita) or Maronite (St. Rafqa).

In this Melkite community, according to Jabbra, saints are valued as protectors of their family, not miracle workers. Here too, she observes, the visual culture of sainthood emphasizes suffering, even tending towards the gruesome.7

One culturally prominent Greek Melkite saint known for her intense suffering is St. Barbara, who was likely born in the ancient city Baalbeck, in the Bekaa Valley. Jabbra recounts an interesting ritual to mark her feast, on December 4, and notes how it has been changing over the years. In addition to marking it with Masses that day, her village has a ritual for children, who travel door to door, reciting a rhyme about St. Barbara and collecting a reward. Housewives have long prepared “ring-shaped cookies, fried cakes dipped in syrup, and boiled wheat (qamh) with sugar and chopped walnuts.” On the same day, women would go up to a St. Barbara shrine in the hills—some barefoot in the cold—to pray. In the early 2000s, she reported that the rituals continued, though they had become a bit more middle-class-oriented and globally influenced, though the religious meaning of the holiday endured. Children went door to door in store-bought St. Barbara masks, a trend that seemed a bit more Halloween-like. By then it was possible to drive, rather than walk barefoot, to the updated shrine on the hill. There, still, people pray and light electric candles and can take home a packet of incense with St. Barbara’s image on it and a cotton swab of holy oil.8

Devotions to Mary in May are also important mostly among women in the same village, according to Jabbra. The month includes individual prayers, Masses, hymn singing and a procession. Jabbra notes how much the community borrows from non-Melkite Catholic traditions: May devotion itself is a Latin rite tradition, and the form of devotion that some used, the rosary, is too. Melkite villagers there also borrow hymns from the Maronite tradition.9

Jabbra also reported on an unusual local Marian tradition, the “Mother of Rain,” that responded to a crucial local vulnerability. The village depends on agriculture, but in this region, rains fall only in winter and need to provide enough water to last the whole year.10

Jabbra knows of three times that Mother of Rain rituals were celebrated between 1973 and 2014. Children went from house to house chanting, “Oh Mother of Rain, rain on us, and rain on our fields, so that our thirsty crops will drink, and grow and feed us.” At each house, they asked for a scrap of cloth and some money. The cloths were tied to encircle the perimeter of the church, and some were hung inside from the lights. The money was deposited as an offering to the church, which is dedicated to Mary. Villagers, she said, did not know the ritual’s origins but just knew that it was a longstanding custom and was efficacious.11

Jabbra also describes a tradition of associating families with particular (usually male) saints for protection and claiming their feast days for family celebrations in the village.

The same Melkite village also celebrates an interesting ritual to honor Lazarus. Though not formally canonized as a saint, Lazarus was raised from the dead by Jesus (John 11: 1-44)—the only person other than Jesus claimed by Christians to have been raised from the dead. In addition to commemorating him at the liturgy on his feast day, the village had an old tradition of children traveling from house to house, one dressed as Lazarus, others as Martha and Mary. Under a canopy they carry, Lazarus lies down and the others chant, “What a happy day!/For the Children who are good/Prepare a Feast for Lazarus/Which makes joyful the demonstrated truth/Bethany, He came to you/Rejoice with the One who loved you/He who covered you with gifts/That faithful shepherd/His sister Martha and Mary/And He was a youth, and the heart was in pain/Rise, living, from the dead/Thanking a generous Lord.” After the chant, Lazarus gets up and the children move to another house. Eventually, another group of children comes along to do the same.12

- 1Nour Farra Haddad, “Figures et Lieux de Sainteté Partagés au Liban,” in Figures et Lieux de la Sainteté en Christianismne et en Islam, eds. Louis Boisset and Grace Homsy-Gottwalles (Beirut: Presses de l’Université Saint-Joseph, 2010), 166.

- 2Haddad claims the there are “around 302 Christian Saints venerated in Lebanon” and that “Saint Elijah is in effect, with Saint George the most venerated saint in Lebanon,” a claim that did not bear out in my interviews, but could be based on her count of 350 Christian places named after them. She does acknowledge the powerful attraction locally to Charbel and Rafqa as miracle-workers. Haddad, “Figures et Lieux,” 171, 179, 183-4; author’s translation.

- 3The entries here are based on on-the-ground research and interviews in 2014 and 2022, supplemented by written scholarship as noted in the footnotes.

- 4Emma Aubin-Boltanski, “Fondation d'un Centre de Pèlerinage au Liban: Notre-Dame de Béchouate,” Archives de sciences sociales des religions 55e Année, no. 151, Fondations des lieux de culte (Juillet-Septembre 2010): 149-168.

- 5Aubin-Boltanski, “Fondation d'un Centre de Pèlerinage au Liban,” 164-5.

- 6Nancy W. Jabbra, “Globalization and Christian Practice in Lebanon's Biqa' Valley,” Middle East Critique 18, no. 3 (2009): 285-299, DOI: 10.1080/19436140903237079; Nancy W. Jabbra, “Traditions in Transition: Change in Vernacular Religion in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley,” Western Folklore, 77, no. 2 (Spring 2018): 141-170.

- 7Jabbra, ,“Globalization and Christian Practice in Lebanon's Biqa' Valley,” 288.

- 8Jabbra, “Globalization and Christian Practice in Lebanon's Biqa' Valley,” 289-90.

- 9Jabbra, “Globalization and Christian Practice in Lebanon's Biqa' Valley,” 291-3.

- 10Jabbra, “Traditions in Transition,” 146-150.

- 11In the most recent iteration of the ritual, it was adult members of the Sisterhood of St. Rita who collected funds and purchased ribbons to tie around the church. Jabbra, “Traditions in Transition,” 150.

- 12Jabbra describes ways that the ritual seems to have changed over time, and variations in how children carry it out. Jabbra, “Traditions in Transition,” 150-4.