Some 20 million people a year visit the Basilica of Santa María de Guadalupe, site of her apparitions to Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatz in in 1531, now the most visited Catholic site in the world. Guadalupe’s famous image, a brown-skinned woman in a starry blue mantle, hands folded in prayer, is ubiquitous in Mexico. She is a remarkable part of believers’ daily lives throughout the year, in their homes, churches, prayers and community life.

The story told in this article is how that devotion is manifest in a concentrated way during the days leading up to her feast, December 12. Newspapers claim that during these days, eight to 10 million people pass through the basilica to visit the image, enshrined above the altar, and the sites of the apparitions on and below Tepeyac, the hill where the shrine is built, in the northern part of what is today Mexico City.1 Streets around the basilica complex are closed for quite some distance to accommodate them. The Calzada de Guadalupe, a boulevard leading to the basilica, is reserved for the continuous stream of pilgrims, many carrying pictures or statues of Guadalupe in their arms or strapped to their backs.

Whether that many millions visit these days is difficult to verify, but it is certainly true that a flood of pilgrims passes through. Most will only be able to spend a relatively short time in the basilica. They line up on the left side inside and are eventually carried by one of four parallel moving walkways that carry them under her image, often while Masses and other liturgies are taking place at the center.

Many of the people who journey here, among those not from Mexico City itself, report that they have walked for days—many said five, six or seven days—and camped nearby as well, just to have a short time visiting their Mother.2 None complained, because the walking itself, and the visit, was their way of fulfilling a promesa, a vow to her, or because they seemed simply happy to be there.

Giving thanks to Guadalupe

The particular needs that drew pilgrims there was sometimes difficult to pin down, not only because of the pilgrims’ modesty or desire for privacy, but because the devotion that brought people to her seems seldom to have been limited to a single need, but to have been shaped by a lifetime of relationship and help. “I love her because she has made miracles for me and my family,” said one woman. “And of course it is her birthday. My daughter is sick, so I’m hoping for a miracle. But I come every year [for the feast], and sometimes during the year.”

A young man, a laborer, reported that honoring her and following her “will help you be a better person and reach your goals.” Another young man reported, “more than anything it is a reason to come to say ‘thanks.’ It is hard to explain. She is among us, so we come to say thanks. It’s part of Mexican culture.”

“Protection is the most common reason,” said another. “And healing.” Asked why there were so many groups of young men, a man said that some come as penitents, though the reasons are varied. “He [pointing to a young man in the group] used to get sick all the time so his mom came, and he got better, so he comes to say thanks. Others come to change behaviors—alcohol, drugs, bad habits, personalities. It is the case that people are outsiders in the Church and formal society, but people still come because they—people—get a sense of belonging and unity.”

A woman who said that she was not as good a Catholic as she should be, said she came to see the image of Guadalupe and to have her own image blessed, and managed to stay for Mass. She said that she comes because Guadalupe “is a Virgin who makes many miracles.” Asked if she was meek and gentle like her image, the woman described her instead as “strong and brave… because she helps everyone. She [has to be] brave with all she does.”

A young man offered, “You have to understand. She is our Mother. In Mexico our mother means everything. And she is our mother. We are devoted to her.” As a mother, she understands, relates, protects, listens, comforts. 3

Most of the pilgrims who walk are clearly people of indigenous or mestizo (mixed) ancestry, and people from the poorer classes. Middle and upper class people there admitted that they were under-represented. It is easy to imagine that some of the class difference is due to the fact that the poor have more needs, but also interesting to note that while the poor have more needs, they more frequently claimed that they were there to thank her for something, more than to ask a specific new thing. They wanted to honor someone so miraculous and always present for them when they needed it. Of course, “there are more indios than criollos [urban, European-blood people] here,” one reported. “She came to him [San Juan Diego, an indio] and she explained that she is here for all of you, to tell you she loves you and will help you, so don’t be worried, so whatever thing you have, she will be there.”

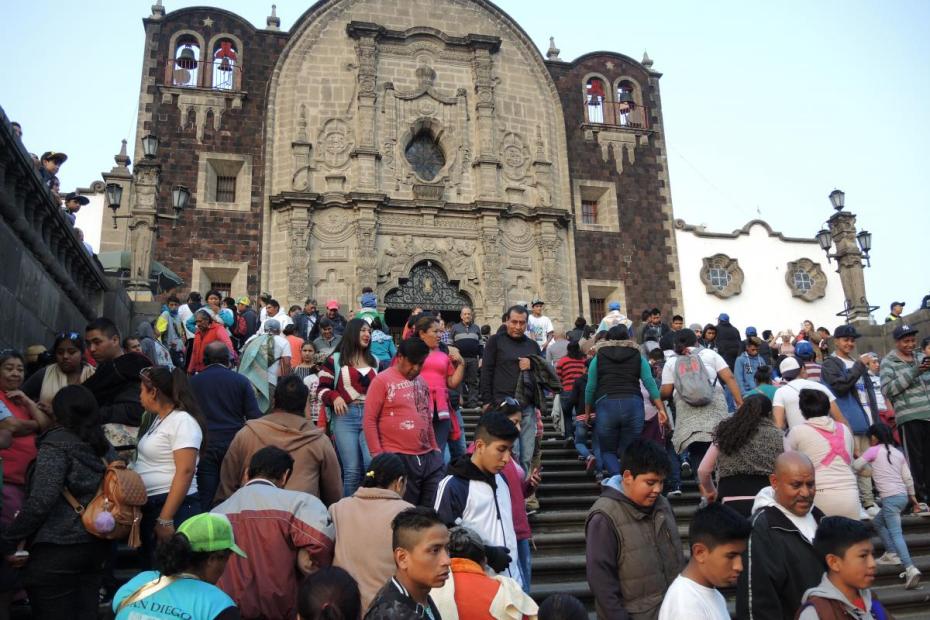

The trek to Guadalupe is almost never a solitary one. People come with family groups, with parish groups wearing matching T-shirts, or (especially among young men) just in groups of friends. As they climbed the steps from the Calzada de Guadalupe, entering the Plaza Mariana, many stopped to pray or kneel or gather as a group before entering the basilica.

Celebrations for Our Lady of Guadalupe take over the Mariana Plaza at the Mexico City basilica for days leading up to her feast, December 12.

Visiting the tilma

Inside the modern, circular basilica, the Guadalupe’s image was visible above the altar, with a Mexican flag draped below. Huge piles of roses stretched along walls on both sides of the image, recreating the sign that Guadalupe gave to Juan Diego to prove the validity of the apparition to the initially skeptical bishop. The flowers dropping from Juan Diego’s tilma are a part of the story that almost every pilgrim knows. A moving walkway took pilgrims behind the flowers and altar, and below her image.

Inside the church, there were daily Masses, but most of the day was taken by visitors making their way up to the moving walkway to get closest to the image. Musicians serenaded in homage to Guadalupe at various times. Even in the very large basilica, only a tiny fraction of visitors could ever be seated inside.

Outside, pilgrims by the hundreds crowded a blessing station to have their images of Guadalupe, and themselves, blessed with Holy Water. This was a near-continuous process. On the other side of the basilica, a large crowd of pilgrims—a few on their knees—climbed the steps all the way up to the baroque hilltop chapel on Tepeyac hill, the site where Juan Diego first saw the Virgin and where he gathered the roses. Along the way were many sites to stop and reflect. Below, some visited several other ancient churches along the plaza, including the old basilica and the chapel of the Indians, all open to visitors. Nearby was a huge underground market to eat or to browse crowded aisles of Catholic religious objects.

The plaza is a site of both intimate moments to mark a promesa fulfilled and a relationship with Guadalupe renewed, and loud, boisterous dancing that could appear to unseasoned eyes as a sort of competition to, rather than participation in the devotion. Quite the contrary, though, the dance is considered by the dancers as a form of prayer. Many people stopped to watch them. Some would stay for the evening events, but most moved on and celebrated those events wherever they were staying.

Overnight, as on prior nights, in the early December cold, people camped out at subway stops, in trucks on the street, in highway medians. Absorbing such vast crowds took patience and help on the part of neighbors, but many said that they see it as their own way of honoring Guadalupe. Neighborhood people and businesses sometimes opened their restroom facilities to the crowds, and in a number of places devotees served food for free to pilgrims who waited in line. In a huge arcade of shops beyond the plaza, pilgrims found not only food, but a huge assortment of religious articles.

The eve of the feast

Inside the basilica on December 11, the evening after sunset is full of “tributes,” in music, words and dance, to mark the Noche Guadalupana, the eve of Guadalupe. These were highly choreographed events, mostly very formal and European in style, but occasionally including at the same time two forms of tradition—European-style robed choir boys singing, and flute-playing dancers in a more indigenous-style dancing around the altar, in front of the image of Guadalupe. The Noche Guadalupana continued for six hours, interspersing organ music, songs of homage by celebrities, children dressed in white, deaf students signing, prayers dedicated to peace, to the disappeared, and to the end of narcotrafficking, and representatives of many cultures and indigenous groups of Mexico, building towards a midnight high point, as devotees gathered in a plaza like revelers waiting for New Years’ Eve.

The midnight high point was a particularly Mexican event, the singing of “Las Mañanitas” to Guadalupe. Las Mañanitas is a traditional song that families sing to their loved ones at dawn to wake them up on their birthday. At the basilica, though, the song was sung joyfully at midnight, the earliest possible moment of Guadalupe’s feast day, by clergy facing her from around the altar, and by the crowds in the plaza. The song was accompanied by guitars and brass, including shouts of Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe, and then by a version of a popular song known as La Guadalupana. A Mass with many concelebrants followed.

Blessing the roses

The square stayed packed into the early hours after midnight. At 2 a.m., there was a special Mass for the Concheros, the devotional dancers in the square. There were Masses again at 5 and 7 a.m. At noon, the cardinal archbishop celebrated a Mass that was followed by a rite of blessing of the roses, when the congregation held up individual roses, and the reading was taken from the Nican Mopohua, the Nahuatl account of the apparition, when Guadalupe tells Juan Diego to go seeking an abundance of flowers growing there, and to take them to the bishop to prove what he hadn’t believed.

The plaza is full of visitors and dancing for the remainder of the day, and the basilica, which hosts two afternoon Rosaries, sees an abundance of visitors throughout the day.

- 1See, e.g., “Con Petitiones a Cuestas, Miles Festejan a la Virgen,” 24 Horas, December 12, 2018.

- 2This entry is based primarily on observations and two dozen group interviews in the plaza, streets, or basilica at the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Dec. 10-12, 2018. Special thanks to Said Pulido for his translation assistance.

- 3The history of the feast, and the inclusion of indigenous elements leads some, including critical scholars, to conclude that devotion to the Virgin is a form of hidden native goddess-worship. However, among her Catholic Mexican-American interviewees, María Del Soccorro Castañeda-Liles reported, “all the women relate to and see La Virgen de Guadalupe (sic) within a Catholic context—she is not an Aztec Goddess” (150). Her college-educated interviewees had encountered in Chicanx studies courses the assertion that Guadalupe was really a baptized continuation of belief in Tonatzin, a pre-Christian Aztec goddess, but none believed it (151-2). Neither was this apparent among the visitors we interviewed at the basilica. María Del Soccorro Castañeda-Liles, Our Lady of Everyday Life: la Virgen de Guadalupe and the Catholic imagination of Mexican women in America (Oxford University Press, 2018).