In many cities in Spain, and elsewhere in the Iberian-influenced world, Semana Santa — Holy Week — is marked by major public processions that recount and ritualize the events of the Passion, providing a visual catechism and giving the masses a chance to participate in the story. In Spain, cities compete to some degree as a point of pride to carry out their processions well, and each has its own feel and particular qualities. In Seville, the ancient city in southern Spain, the scale and organization of the processions are unparalleled. From Palm Sunday to Holy Saturday, 60 official processions traverse the center city from afternoon deep into the night. In 2016, 63,145 men, women and children, plus musicians and costaleros, the men who carry the images, processed through the streets.1 Twelve more processions — those of newer confraternities that cannot be accommodated during Holy Week — processed on the Friday and Saturday before Palm Sunday. Another procession announced the Resurrection on Easter morning.

Seville is a tourist city, and tourists travel here during Holy Week to see the processions. But time spent with Sevillians waiting for and watching the processions, or with Sevillians who walk in them, makes clear that these are not merely or primarily tourist attractions, but are deeply a part of Sevillian culture. The practice is integral to the city’s religious and cultural identity. The brotherhoods and confraternities that organize the processions count more than 200,000 members in a city of 700,000 people, and are active throughout the year.2 They and other locals follow the events with incredible attentiveness. However diminished religion may be in other ways in Spain, in Seville the processions are a vital social institution. Processions are full of young people and so are the audiences that gather to watch them.

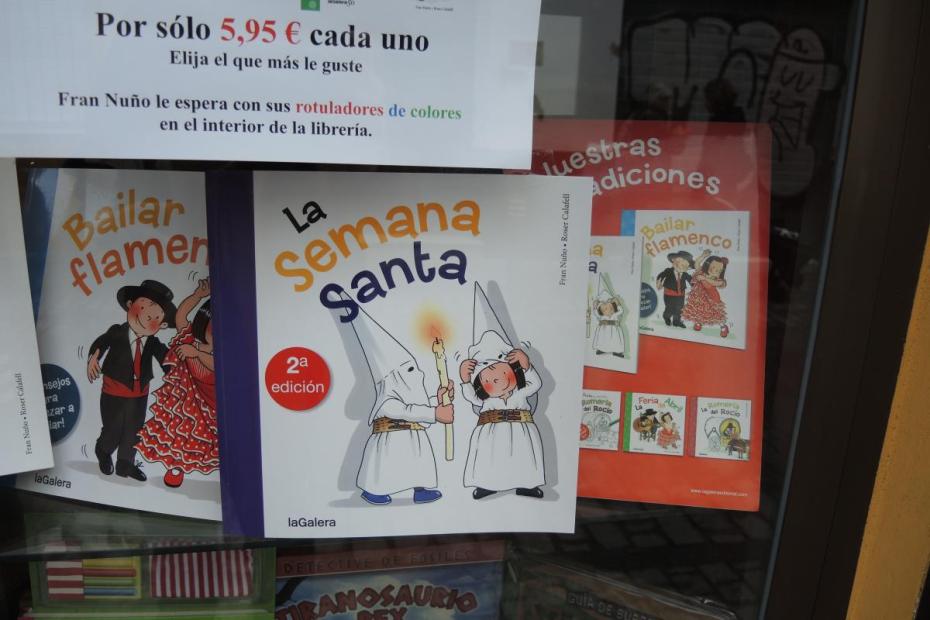

Media images of Holy Week in Seville often give a sense that the events are extraordinarily solemn and even stern, that they privilege the suffering of the Passion over the triumph of the Resurrection. The famous pointed-cap tunics of the processing nazarenos, and the sheer number of Passion processions (only one of which, sparsely attended, is on Easter morning, and dates only to a confraternity founded in 1969), reinforces that notion, but gives a very incomplete picture. Quiet solemnity and sacrifice is only a part of the picture. As one confraternity leader put it, “Seville’s is a happier way of living Holy Week… For us, we know what the end is. [Holy Week] is a celebration for us.” Children who process as nazarenos hand out candy to other children sitting along the route.3 People waiting for processions greet friends, enjoy each other’s company, share accounts of the various processions, and (usually) turn silent as the main images pass by. These could often be mistaken as merely social occasions, until they turn reverent, and then turn social again.

History

The processions have been a fixture of Sevillian life since the 14th century, but detailed records are scarce until the late 16th century. Some confraternities were originally, or at some point in their histories, organizations of workers — boatmen, merchants, ceramicists, gardeners and bakers among them. Las Cigarreras, an ancient confraternity, took on that appellation after if was relocated to the chapel of the royal tobacco factory of Seville in 1904. Others were originally ethnic or racial religious groups. Los Negritos was, until the 19th century, open only to black men; Los Gitanos were gypsies. Still others were for residents of Seville born in other cities.4 Others were founded to take on a charitable mission: El Amor, the Love, founded at the end of the 16th century, began with a social mission, to care for prisoners, and El Dulce Nombre, the Sweet Name was founded to care for orphan girls.5 Over the centuries, confraternities merged, went dormant, or changed locations.

The processions were interrupted by the devastations of the Napoleonic invasions (1807-1814), again from 1820-1825. The late 19th and early 20th centuries were a period of intense growth for the confraternities. By the last third of the 19th century, the current form of the procession — the elaborate pasos, embroidery, and the musical accompaniment of marching bands — was set.6 From 1932-1939, during the Second Republic and the Spanish Civil War, the processions were halted or barely took place. But even those events are said to have given impetus to renewed growth and fervor for Semana Santa devotion thereafter.7 The number of processions and the size of the confraternities has grown significantly, as the city has, over the course of the late 19th and 20th centuries. The urban expansion far beyond the old walls of the city in this era meant that many processions necessarily became much longer and more difficult, given the distance to the cathedral, through which they all pass.

The reforms of the Second Vatican Council and the decade thereafter aimed to pull Catholics in new directions, de-emphasizing many Tridentine forms of devotion. The Council led to significant changes in Catholic life in Spain in a whole variety of ways, but its impact on Semana Santa remains less pervasive than one might expect. The confraternities modernized in some ways, emphasizing post-Vatican II theological catechesis and dropping some baroque trappings. The processional culture adapted, but was not bumped from center stage. It is safe to say that attendance at Holy Week processions exceeds attendance at Holy Week liturgies, and certainly at Easter liturgies. In the post-Vatican-II era, the Holy Week processional tradition has actually been extended.8 At least 12 new processional Brotherhoods have been formed since Vatican II. El Resucitado, added in 1969 as one outcome of the reform, processes on Easter. The growth in numbers has been continuous and significant enough that most of the new confraternities have had to be accommodated on the Friday and Saturday before Palm Sunday. Among them are Padre Pio (2005), San José Obrero (2013), and San Jerónimo and La Milagrosa, which began processing in 2016.

Fidelity to tradition is extraordinarily important to the confraternities. Yet it would be a mistake to imagine that the processions or confraternities are unchanging. Confraternities meet each year to discuss modest changes, choose music and choose to add images to pasos, the carried “floats” of Jesus and Mary.

The processions

In the two days before the start of Holy Week, 12 confraternities process in the city, though not necessarily in the center city, and not through the cathedral. The primary processional activities begin on Palm Sunday. Each day through Holy Saturday, six to nine processions march through the center city. The first typically begins in the early afternoon, and the last returns to its church by 3 a.m. Each procession has a designated route and is carefully timed to process through the cathedral at a specified time.

Palm Sunday begins with an afternoon procession of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem by the confraternity La Borriquita, the little burro, so named because its paso features Jesus riding a burro into Jerusalem with a crowd of figures gathered around him. The 850 robed penitents of this confraternity are all under 14 years old.9 Eight more confraternities, ranging from 1,300 to 6,500 processants each, process that day along different routes to the cathedral, returning to their churches as late as 2:30 a.m. A similar number process Monday, Tuesday, and Wednesday nights.

On Holy Thursday, the number of processions increases, continuing through the night into the early afternoon Good Friday. Eight processions are organized in the normal time frame, followed by La Madrugá (dawn) processions, which commence at 1 a.m. during the night between Holy Thursday and Good Friday, and begin to make their entries to the cathedral at 3 a.m. These processions are the most solemn of the week. Eight more process beginning in the early evening of Good Friday, and five more on Holy Saturday. On Easter Sunday, only one confraternity, El Resucitado, processes, from 4:45 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.

The longest procession, El Sed, takes 14½ hours to travel from the parish to the cathedral and back. The shortest, the Borriquita children’s procession, is 3½ hours, and the rest run the full gamut in between. Penitents don’t normally eat or drink during that time. To an observer watching the procession pass from a fixed point on the street, the average procession takes about 45 minutes to pass. The largest, La Macarena, which takes place during La Madrugá in the early hours of Good Friday, has 3,050 nazarenos (the costumed penitents), and takes one hour and 50 minutes to pass.

The route of the procession is predetermined and carefully timed. Each begins and ends at the confraternity’s home church, along a route that (except for the pre-Palm Sunday processions) passes through the interior of the cathedral. The enormous doors of the cathedral allow each paso to be carried easily in and out. Any threat of rain means that a procession is cancelled, out of concern for the pasos and images. On Holy Thursday 2016, the pasos of some afternoon processions had to be diverted to safety in nearby churches as sudden storms approached. Disappointing as that can be, given the amount of preparation that goes into the processions, it is also taken as a reminder that humans are not always in control of things.

The form of the procession is quite consistent, enough to surprise outsiders who might wonder why “the same thing” could be interesting to watch over and over again all week. Nonetheless, processions can be powerful and passionate, by virtue of the silence that suddenly accompanies them, the music of the bands, the sheer number of penitents, and the shaking movement of the often large, elaborate images.

Each procession is led by a large cross, accompanied by elaborate silver or gold lanterns. Behind that, a group of processants carries elegant banners, the book of rules for the confraternity, and other insignia of the confraternity. Following that are large groups of nazarenos, the confraternity members who dress in tunics and capirotes (or capuchones), the famous tall, pointed, conical hats whose cloth drapes down to cover the face, except for the holes cut out for the wearer’s eyes.10 Each confraternity has its own colors and insignia. Media images of the processions typically feature white or black tunics or capirotes, but confraternities have adopted a range of colors for their costumes, including purple, green, blue, red, and even salmon pink. The nazarenos are followed by candle- and incense-bearers in fine vestments, then by the confraternity’s elaborate paso — the word is also Spanish for “he passed” — the carried platform that bears an image depicting some aspect of Jesus’ Passion. The paso, which is typically very heavy and elaborately detailed in gold, is carried by several dozen men hidden underneath. It typically rocks or shakes rhythmically from side to side as it is carried through the streets.

The paso is generally followed by musicians, typically a brass band with marching drums. Penitentes — confraternity members carrying crosses over their shoulders, wearing the same outfits as other nazarenos but without the pointed cones in the hood, generally follow the musicians, and are in turn followed by more nazarenos, then candles, incense and a paso of the Virgin, followed at the end by more musicians. Most confraternities have two pasos, but there are a small number of brotherhoods who have one or three pasos. The confraternity’s spiritual director, a priest, often has a place in the procession, but is usually dressed simply in clerics wearing a pendant that signals confraternity membership. All the rest of the processants are lay people. Some penitentes say that they pray the Rosary while they walk, while others say that the act of walking is in itself a prayer.

The nazarenos are organized into subgroups, each led by a captain who organizes them and insures order and discipline. The processants in most confraternities are intergenerational. Persons who have marched the longest number of years get to march closest to the pasos.

For centuries, criminals in Spain wore the pointed, conical capirotes in public as symbols of humiliation and punishment for a crime.11 The face covers on processional capirotes are supposed to provide anonymity for the nazarenos, and nazarenos are typically expected to wear them while walking silently on their way to and from the procession. Exceptions to that rule are made in cases where the procession is already exceptionally long. In reality, onlookers often manage to recognize friends and family in the procession, and stop them along the route. Some processions actively discourage this, but others do not. On Palm Sunday, some nazarenos even had a boyfriend or girlfriend walking alongside them in street clothes.

Bearing the weight, communicating feeling

The pasos are typically carried by 35-45 costaleros — porters, all men, all of the same height — who bear the heavy structure and statues and carry it through the streets for so many hours. Each paso has a wooden frame underneath, with cross beams. Costaleros stand in rows beneath the beams and bear them on their shoulders and across the back of their necks. The costaleros are hidden beneath the gold or silver frames and velvet skirting of the pasos, packed shoulder-to-shoulder, unable to see where they are going, so a capataz, or foreman, signals and directs them from in front of the paso. Until the 1970s, the costaleros were all dockworkers, paid to carry the floats. Today, almost all pasos are carried by volunteers.

Confraternities and onlookers pay special attention to the movement and turns of the paso, and the manner and dignity with which it is borne, which are much more precisely choreographed than any other aspect of the procession. Frequent stops to rest are a necessity, given the immense weight. The capataz uses an elaborate brass or wood knocker on the front of each paso to signal the time for the costaleros to stand up again after their periodic breaks in the street.

The costaleros of various confraternities actually employ a variety of different “steps” for carrying their pasos. These dance elements are commonly are said to give the paso a “sober,” “elegant” or “jubilant” sense of motion. The anda trianero, or trianero walk, for example, is a set of steps sideways, forward and backward used for the images where Jesus falls three times or confronts the power of Caiaphas.12

The costaleros are physically obscured from the onlookers, but onlookers are very much aware of what it takes to carry the heavy pasos. People cheer on the costaleros at various points, and the costaleros keep the pasos rocking modestly but rhythmically from side to side, providing an element of movement and power that a carriage supported on wheels could never match. When costaleros cycle out for a rest break, they mill about visibly among the penitents, still wearing their costals — the distinctive cloth head and neck gear that protects their heads and necks when they carry the paso. At least as much as any group in the procession, they symbolize an ideal Christian life for onlookers: they bear the burden of making it meaningful and carrying it on, and signal that at least in Seville, the Christian life is regarded not just an individual challenge, but as an effort that requires a whole group working together.

The images

Each confraternity is associated with a particular church or chapel, some of which exist essentially for the confraternities, and are only supported today because of them. The pasos and other regalia are stored there year-round, and the confraternity meets and prays there. Confraternities typically have two pasos, one of which features an image of Christ, while the second features an image of the Virgin.

The primary thematic focus of the images of Jesus communicate his humiliation, agony and suffering. Jesus sometimes wears velvet robes, but more often his torso is bared and bloodied. Whatever his bodily condition, he wears a sort of crown with three silver or gold rays that point upwards from his head. He is often dark featured. One much celebrated image of the crucified Jesus, el Cacchorro, is said to have been carved in the 19th century to capture the face of a gypsy man after he died in agony from a knife brawl.

The most common images of Jesus on the pasos feature him carrying the Cross, often accompanied by elegantly dressed statues of the weeping women who accompanied him at the end, or feature him crucified. Others feature the Last Supper, Judas’ betrayal and kiss, the sentencing of Jesus, Jesus before the high priests, Jesus stripped of his tunic, Jesus before Pilate, Jesus scourged at the pillar, Jesus with the crown of thorns, Jesus crucified on Calvary with the two thieves, the descent of Jesus’ dead body from the Cross. They are not chronologically ordered, except for the first and last of them. Some of the images have devotional, rather than passional, names related to them, such as the the crucifixion scene known as the Christ of the Good Death, or the Cristo del Amor, the Christ of Love, an image of Jesus crucified that is used to manifest that confraternity’s mission to serve prisoners’ needs and to show them Jesus’ love.

The pasos of the Virgin usually situate her in regal, if emotionally desolate, splendor, alone among a sea of tall candles. She is crowned, wearing exquisite embroidery, often wearing donated jewels. In contrast to some of the most popular brown images of Jesus, Mary’s face is typically very pale. Though she is emotionally attached, her separateness is striking. She is occasionally portrayed with the Apostle John or other mourners next to her, looking distressed and at a loss to comfort her. More often — unlike Jesus who is often portrayed with many biblical figures — she is alone, and inconsolable. Though Jesus’ pasos are always open to the sky, the Virgin is always processed under an elaborately embroidered velvet palio, a flat canopy a that is affixed to the paso. The only parts of her body that are visible are her face and hands. These are carved to display the maximum possible emotion. Her face is tearful and suffering, and her hands reach out in a variety of ways. From the front, all but her sad face is often obscured by the blaze of very large candles. When she passes, all one can see of her is an elaborate embroidered cape that fans out behind the paso.

Most images of her represent particular devotions: The Virgin of the Rosary, the Virgin of the Valley, the Virgin of Mercy, the Virgin of Sorrows, the Virgin of Peace, the Virgin of Tears, the Virgin of Grace and Protection. The most popular Marian image here is María Santísima de la Esperanza Macarena — the Mary Most Holy of Hope Macarena. “Macarena” refers to the name of a one-time city gate where the church and the image are located. As is the case with several other Marian names in Spain, Macarena is, in honor of the Virgin, a fairly common name for women from Seville.13 The image, carved in the 17th century, shows Mary in tears, and is one that many Sevillians find the most touching. The baroque church where she is housed, built for the Confraternity of Macarena, is dedicated as a basilica.

The pasos themselves are quite elaborate, in baroque, mannerist, neogothic or neoclassical styles. None could be described as modernist. Those carrying images of Jesus are usually painted or leafed in gold, sometimes in silver or mahogany. The paso for the Virgin is silver.

The confraternities work year-round to keep the pasos in prime condition, employing teams of embroiderers, silversmiths, and restorers to ensure that pasos are in perfect condition.

The audience: aficionados

A huge proportion of the city comes out to see the processions along the routes. Onlookers participate by watching from the sides, not from walking at the end of the procession, as happens in processions in some other countries. In the blocks just before and after the cathedral, where all processions must pass, the city sells reserved seating to families who renew their membership annually. On other blocks further out, where there is no reserved seating, families crowd the streets during daylight hours; in the evening the viewers tend to be young people (their parents, they say, stay home to watch on TV).

Two days of the processions merit special dress for onlookers. On Palm Sunday, which is often said to be the biggest day in Seville, men typically dress in new suits. Even — perhaps especially — teenage boys are dressed to impress. On Holy Thursday, many people dress up as well, and some women have begun again to wear traditional lace mantillas in the squares, though that seems to be more a fashion statement than a devotional one. One surprising aspect of the Holy Week procession is that men, especially young men, are often the majority of the observers. Likewise, they remain the majority of the processants. One said that it has been like that for years, though the confraternities are open to men and women as leaders.

Each morning, confraternity churches and chapels are opened to the public and are crowded with visitors who come to see that day’s pasos before they process. Some churches have long lines that extend two blocks or more.

To visitors, including this author and a Spaniard from Madrid, the form of the processions and the style of the images seemed surprisingly repetitive, marked only by minor differences from procession to procession. Asked about this, interviewees responded repeatedly, in a friendly or amazed way, that nothing could be further from the truth. They described details about the visage of statues — the expression on particular images of Jesus or Mary, the shape and turn of hands, the tears on the Virgin, the tilt of the head, the design of the paso, all of which had great meaning to them. People who were not members of confraternities explained that they had special devotion for particular images. The reason for that devotion was often linked to other events in their lives, but the fine details of the image and its particularities were important. The images were not interchangeable, nor were the particular moments or religious insights that each was designed to represent.

Viewers on the street and confraternity members often could talk with surprising fluency about which particular “school” an image belonged to, i.e. whether an image was an example of the Andalusian, Castilian or Baroque school. A surprising number knew which carvers carved which statues, and when. When they visited various churches the morning before the processions, when the pasos were on display, they often had their pictures taken with the pasos, and commented about fine details in each. The statues and pasos require considerable upkeep year round, employing a number of master carvers and embroiderers, and many people knew who was repairing what in the active local workshops.

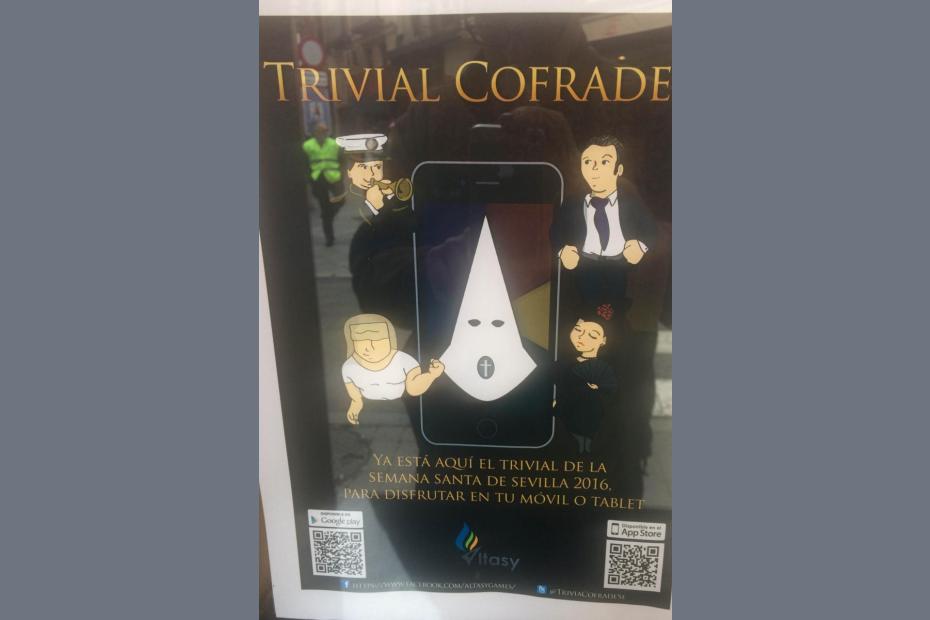

On the street, it was easy to strike up a conversation with those waiting for the arrival of a confraternity. In almost every instance, viewers could provide detailed answers to which confraternity was processing in what order, what the routes were, and what time a procession would make it through a certain point. It is easy to find resources that help them keep up with such details. A bank and newspapers printed this information, but a popular, annually updated app, El Llamador Sevilla, gives smartphone owners information, timed itinerary, and route maps for all of the processions. Bookstores in the city sell many books on the history of various confraternities, with more indepth information. For aficionados and would-be aficionados, there is even a trivia app, Trivial Cofrade: Semana Santa de Sevilla, with categories for the history, imagery, music, photography and curiosities. The questions require fairly extensive knowledge of the events to answer correctly.

After the intense activity of Holy Week, central Seville is surprisingly quiet on Easter Sunday. In a number of churches visited during morning and noon masses, the crowd is significant, but hardly overflowing. Interviewees noted that Seville has few specific Easter traditions. Modest crowds witnessed the procession of El Resucitado, the Resurrected One, a procession that dates back only to 1969. Some people go to visit the churches later in the day because processional statues are often still lowered for people to see. There are no special traditions of Easter foods or Easter candy, or traditions of special family meals, as in many other places, though there are food customs during Holy Week, when children do receive candy and seasonal sweets, or when they eat fish on Good Friday.

The processions, many interviewees noted, are not the end in themselves, but especially an occasion for coming together. It is important that they are done well, that the occasions are properly commemorated and that Christ and the Virgin are properly honored. But the work of the confraternity lasts year round, and after the processants take comfort that a procession went as well as it should, there are always plans to be made to look forward to the next year.

- 1The numbers are calculated from the app El Llamador, from Canal Sur Radio, which provides a full listing of confraternities, routes and times. Special thanks to Teresa Dolado Martin for her assistance and able translation, and to Rosario Cumpliso and Lola Garcia for their help gaining access to the Cathedral and cofradias. The words “brotherhood” and “confraternity” are used interchangeably here, as they are often in Seville and in studies of the confraternities like Jesús Luengo Mena’s Compendio de las Cofradías de Sevilla que procesionan a la Santa Iglesia Catedral en Semana Santa, Ediciones Espuela de Plata, 2007, 12-13.

- 2El Llamador. It is important to note, however, that some people belong to more than one confraternity. The broader Seville metropolitan area comprises about 1.5 million people.

- 3Catholics from other parts of the world may find this surprising during lent, but interviewees here cited it as an appropriate manifestation of the gospel passage, Mt 19:14, where Jesus says “let the little children come to me.”

- 4Both ethnic names are the common appellations of the group. Los Negritos is formally titled “Ancient, Pontifical and Franciscan Brotherhood and Brotherhood of Nazarenes of the Most Holy Christ of the Foundation and Our Lady of the Angels.” Los Gitanes is formally titled “Royal, Illustrious and Fervent Sacramental Brotherhood, Blessed Soul and Brotherhood of Nazarenes of Our Father Jesus of Health and Holy Mary of the Crowned Angustias.” See Jesús Luengo Mena’s Compendio de las Cofradías de Sevilla que procesionan a la Santa Iglesia Catedral en Semana Santa.

- 5There is some debate over the degree to which confraternities were founded with a charitable, more than a devotional, purpose. Here I rely on the self-understandings and histories presented by confraternity leaders today.

- 6José Manuel Castroviejo López, De Bandas y Repertorios: la música procesional en Sevilla desde el siglo XIX (Seville: Editorial Samarcanda, 2016), 113.

- 7Pablo Borrallo, et. al., Atlas de la Semana Santa de Sevilla (Sevilla: Ediciones Alfar, 2016), 39-52.

- 8Confraternities often have a variety of dates associated with their foundings, since few are prepared to process right away. Dates listed here are the years of their first official procession.

- 9Zamora, Valladolid, and Cartagena, among other cities in Spain, also begin Palm Sunday processions with a borriquita and children in the procession. In 2016, rain delayed the procession of la Borriquita until evening.

- 10Americans, and presumably some other readers around the globe, will recognize that a white version of this costume was adopted by the racist and anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan in the United States. In Seville the costume, half a millennium old in design, carries no such connotation.

- 11In this sense it might best be compared to the dunce cap that was once put on children in school in the English-speaking world to humiliate them.

- 12Pablo Borrallo, et. al., Atlas de la Semana Santa de Sevilla (Sevilla: Ediciones Alfar, 2016), 94. An article in a Sevillan newspaper after Holy Week 2014 parses ten basic costalero “steps” or styles: M.J.R. Rechi, “Las diez cuadrillas que mejor han andado en la Semana Santa de 2014,” ABCdeSevilla, 23 April, 2014.

- 13The popular dance song, about a woman with this name, is not to be confused with the María Santísima de la Esperanza Macarena. The song, very differently, refers to a young woman named Macarena. Many of those who dance to the song at weddings might be surprised to learn that the lyrics celebrate a different reality, about a young woman who quite embraces her own sexuality and cheats on her boyfriend with two other men at once.