Saints are invoked in Soouth India as persons who can bestow blessing or healing in return for proper devotion offered. Certainly, Mother Mary, St. Alphonsa, and St. George all represent ideal models of Christian behaviors for women and men, but many more of the stories around them seem to center on miracles, cures, and protection.1

Mary and the saints help to establish a solid link for Christians to a faith that is ancient in Southern India, not "foreign" and colonialist as many Hindus might claim. Christian Indians claim the Apostle Thomas's foundation of the church after 52AD as a first source of ancient roots, though interestingly the Apostle's statue is not frequently seen in churches in Kerala. The St. Mary's Forane, or Kuravilangad Church, in Kottayam, a Syro-Malabar church and shrine, draws its legitimacy from an appearance of the Virgin at a spring in 105 AD. That appearance of Mary, which they cite as the first Marian appearance in history, is used to suggest that Mary has a particular love for India and chose to appear there first before going out to the rest of the world.

Marian shrines tend to focus on Mary as mother ("Mary Matha"), rather than on Mary as a solitary figure. While the Sacred Heart of Jesus is a very popular image, the Immaculate Heart of Mary is less frequently seen: images of Mary tend more often than not to show her with the child Jesus, or in a pieta. At Kuravilangad, as at Velankanni, where Mary appeared, she is connected in a maternal way to the children she appeared to.

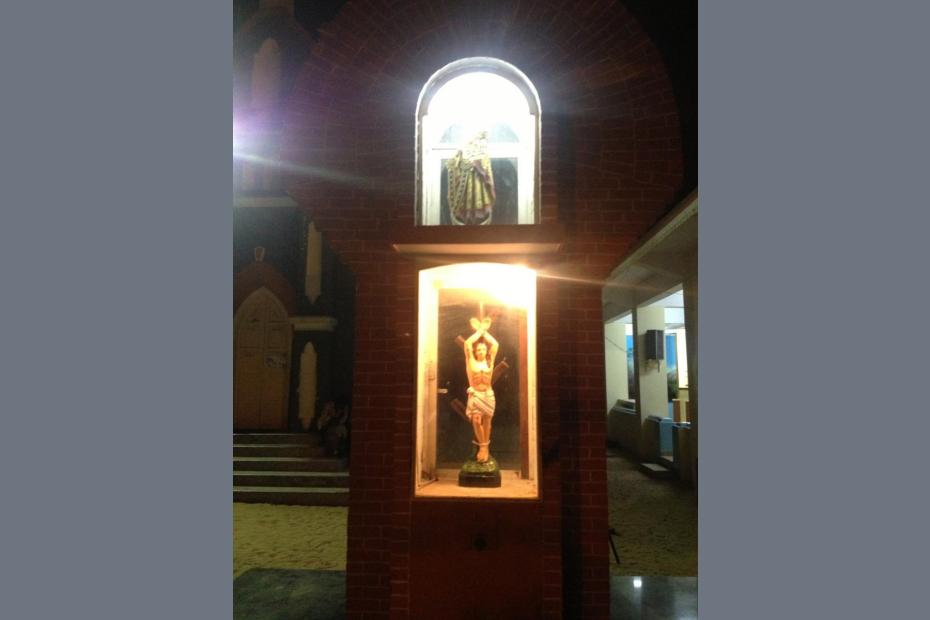

After Mary, the saints most frequently seen in Southern India are defender/protectors: St. Michael, the protecting Archangel and demon slayer, and St. George, the dragon slayer. St. Sebastian is popular in many areas especially apparently among Dalits for the signs of suffering he bears. European saints like St. Anthony and St. Jude – both miracle workers – and St. Thérèse of Liseux have followings, but the cult of St. Thérèse has been superseded by that of St. Alphonsa, who bears many similarities to Thérèse, but is native to Kerala and is from the Syro-Malabar church.

The values ascribed to St. Alphonsa generally focus on two themes: her suffering in silence through intense pain, and her love for and goodness to children. She burned her feet badly on coals as a youth, and miraculous healings ascribed to her are related to legs and feet. In Kerala, her birthplace, burial place, and convent have become shrines, and her picture can be seen all over, including on ads for a jewelry store, a travel agency, spices, tiles, a tailor and on candles for sale.

St. Alphonsa is generally described in fairly passive terms, as having suffered quietly, but her official image, venerated by many and distributed by her fellow Clarist Sisters, shows a very strong, determined woman. She looks undeniably Indian, though in a Roman Catholic nun’s veil. Corinne Dempsey writes that for many Syrian Christians she spoke to, this saint beneath that western nun’s veil is something of a rebuke to the West. For them, St. Alphonsa is an Indian bulwark of old values against the “corrupting effects of material comforts and worldly values” that they see coming from the West.2

In her 2001 study of Kerala sainthood, Dempsey argues that “St. George is by far the most powerful, or at least the most popular saint, with the occasional exception of Mary, the Mother of Jesus. Furthermore, aside from Mary and St. Joseph, St. George is the only saint who could be considered a ‘universal’ devotional figure among non-Protestant Christians in Kerala: Jacobites, Orthodox Syrians and Catholics of both the Syrian and Latin rites, regardless of their doctrinal and political squabbles, all claim St. George as their own.”3 George is a popular name in the area. St. George’s presence as a devotion in Kerala long predates the arrival of European missionaries, and has survived recent historicizing efforts to dethrone his story as fiction.4

His “story” is one of heroic action, and has to do with the defeat of a dragon to save a princess – a triumph over the forces of evil and disorder. In that sense, he is much like Ganesh, a Hindu deity, who is a fighter against demons and remover of obstacles.

Images of Mother Teresa of Calcutta are visible on businesses at Velankanni and in a large poster at St. Mary's Basilica in Bengaluru, but at least in the south, she has not been venerated at shrines.

A Different Situation in the Northeast

Khasi and Pnar Catholics in India's Northeast have remarkably different family structures and norms. These Matrilineal cultures are worth exploring on their own.

- 1This was abundantly evident in research for this project in 2013 and 2014. It was validated by an observation Dempsey heard from “a middle-aged man from Kochi” that estimated only 10% of Indians come to St. Alphonsa’s shrine out of admiration for her lived model of holiness. “When pilgrims come here saying that they are trying to learn more about and improve their sense of holiness or purity, it is most likely a lie.” Corinne Dempsey, Kerala Christian Sainthood: collisions of culture and worldview in South India, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 93-4.

- 2Dempsey, Kerala Christian Sainthood, 5.

- 3Dempsey, Kerala Christian Sainthood, 35.

- 4Thus, as Dempsey points out, “St. George’s name has been removed from Catholic liturgical calendars, and churches can no longer be built in his honor.” Dempsey, Kerala Christian Sainthood, 45.