Irish Catholics of almost all ages are quite aware that they have lived through a revolutionary religious transition. One of the most remarkable aspects of the Catholic story in Ireland is its recent transformation from the country with perhaps the highest rate of Catholic practice to a country where Catholic life is spoken about in the past tense.

Throughout the 19th century and most of the 20th, Catholicism undoubtedly had a “moral monopoly” over Irish life. A survey conducted in 1974 found that Sunday Mass attendance was 91 percent. In 1984, however, this figure had dropped to 87 percent and by the late 1990s, only about 60-62% of Catholics attended Sunday Mass. 1 Even in the 1990s Ireland had, by far, the highest levels of religious practice in Europe.

According to the 2016 census, fewer than three-quarters of people in Ireland even claim to be Catholic.2 Religious houses are closing and are for sale, and parishes are forced to combine resources, such as youth programs, in order to cope with a radically different situation: a serious decrease in priests. Between 1975 and 2005, the population of Maynooth, the major seminary, dropped almost 90%.3 As of 2014, there were only 2 priests under age 40 in the entire archdiocese of Dublin. Although surveys still claim relatively healthy levels of Mass attendance compared to the rest of Europe, clergy and laity in Dublin interviewed by Catholics & Cultures reported Mass attendance to be in the single digits in many parishes. A teacher at a Catholic primary school in Dublin reported that when he asked them about it on return from Christmas holiday, none of his students reported having gone to Mass at Christmas, though all were baptized and had received first communion. Institutional loyalty is fragile at best. Despite this, Irish citizens still overwhelmingly identify as Catholic and participate in the sacraments that mark the stages of life, and there is a great deal of evidence that Catholic ideas continue to shape a good deal of the imagination and worldview of the Irish people.

Two factors are generally cited by scholars (and often inferentially by ordinary lay people) as immediate causes of this decline. The transformation of society and consciousness wrought in the era of tremendous new prosperity known as the “Celtic tiger,” from the mid 1990s until the property bust of 2008, is one source of change. The second, which unfolded with full force during the same period, is a clergy sexual abuse crisis that rocked Ireland and resulted in a deep cynicism by laity about a clergy toward whom they had formerly been extraordinarily deferential. Revelations of priests and a bishop who had fathered children diminished priestly authority. Subsequent scandals about past incarceration and physical abuse of children at industrial schools, and women at “Magdalene laundries,” convent-run houses for pregnant but unmarried women, also rocked Ireland. A slow cultural change in the ’80s and ’90s was probably necessary for the allegations of clergy sexual misconduct to even become public, but the abuse crisis radically changed things.

The interviews conducted for the articles on Ireland on the Catholic & Cultures site, in addition to the cited resources, are based on extended interviews, formal conversations and parish visits.4 Attitudes toward clergy ranged from anger to resignation and mistrust, even as interviewees, echoing the past, sometimes suddenly reversed that sentiment to place one priest or another on a pedestal.5 Although sexual expression of all sorts had been policed by the Irish Church by means of civil law, moral proscription and common shaming, it is now clear that sexual abuses against children, women and seminarians had been allowed to pass. Media articles and public investigations have kept the unfolding scandal at the forefront of consciousness for years. In a culture where the laity had long shown unusual deference and respect to clergy and religious—or at least been expected to in public—such revelations were dynamite.

Historical Background

The Irish national story is defined by the country’s relationship to the United Kingdom, which brutally subdued the country in a number of ways, subjugating the Irish, confiscating lands, and radically limiting economic and educational opportunities. Attempts to Protestantize Ireland were very much part of the plan of subjugation. 18th-century penal laws were directed at Catholics, and Catholic church buildings were forbidden until early in the 19th century. Some of the force behind Ireland’s collective attachment to Catholicism was certainly linked to Catholicism’s juxtaposition to the United Kingdom’s Protestant rule.

In the 19th century, as those laws were relaxed, the Irish began to build grand churches and support a clergy that would have as high a status as the Protestant clergy had. The Church cemented its role in the Irish cultural imagination as a representative of the Irish people in resistance to English rule. From the mid 19th century to the latter part of the 20th century, the Church was the primary builder of schools, hospitals and human service institutions, staffed by burgeoning numbers of priests, nuns and brothers. Globally, too, the Irish had a huge impact. It is said that in the 1960s, "one in every 120 Irish adults worked abroad in a missionary capacity."6 In a country with few large business enterprises or major non-ecclesial organizations, the church had a near monopoly on education. One could suggest that its only competition was the state, but the two often worked hand in hand.

The Qualities of Irish Catholic Culture

Commentators debate the core characteristics of Irish Catholicism that grew out of this. Dermot Keogh focuses on its clericalism and the overweening and legalistic moralism of the Church, and the intense awareness of sin and careful accounting made of it. Irish Catholicism in most of the 20th century was known for its focus on sin and hellfire, for casuistry the legalistic parsing of rules about how far one could go without crossing a boundary to perdition.7 As Tom Inglis notes, it was a system in which “one could be forgiven for breaking the rules of the church, but questioning them was a different matter.”8 In terms of attention to church rules, the Irish might be said to have been exemplars of what one meant by using the curious phrase “strict Catholic.”

In interviews and group discussions, committed Catholic adults often talked about having been raised in a context where they were more rule-guided, more guilt-driven and worried about being good enough for God, more concerned about making mistakes than anything else. As adults, their transformation had come when they realized this, and began to reshape a religious life that was more about closeness to God. Many thought that the church had played a significant role in helping them to realize this, but indicated that the transformation posed something of an existential adjustment, a breaking up of an old self.

The negative characterization that would make the laity out to be innocent victims has great currency in contemporary Ireland, perhaps especially in light of the hypocrisy of the abuse crisis. It certainly fails to capture lighter aspects of Irish life, and beliefs that were about more than fear. Some interviewees were more nuanced, recalling archbishops who were tyrants and clergy who were beloved but who also became wrapped up in scandal. Still, as even one of those interviewees said, “We were dictated to… it wasn’t the love of God, it was being dictated to. The poor, the poor were really poor then, and they [the bishops] were rich, and we adored them and such. But it’s when you get older and you look back at the picture and you say, it wasn’t a good picture… It doesn’t make sense to me anymore.”

Among the characteristics of Irish Catholicism that no one disputes are an emphasis on the sacraments, including frequent confession and Mass attendance, and attachment to a range of devotional practices. The Rosary, novenas, Stations of the Cross, practices of devotion to saints, and exposition of the Blessed Sacrament all were regular parts of Irish Catholic life.9

After the Council

Many of the harder qualities of Irish Catholicism abated significantly after Vatican II, a period of critical reflection on the Church in Ireland. Interviewees who referenced that period talked about parish pilgrimages and social events that were really joyful occasions, about nuns in the community who were beloved. But this whole period is almost entirely overshadowed in conversation by talk of earlier strictness or abusers. Interviewees who were asked about prayer today tended to have a fairly gentle relationship to prayer, and a sense of God more as lover and protector than as judge. Both things were surely influenced by the Council. They prayed that God might remember friends and family, and care for these.

It is important to note that the secularization that marks Ireland today was not directly, or at least temporally, connected to Vatican II. Unlike the rest of Europe and the United States, Ireland did not see significant diminishment of Church attendance until more than 30 years after the close of the Council. People talked about learning during this time to make their own existential choice in favor of God and Church during that period, but overwhelmingly, those are the choices they made.

Secular Ireland?

In very many ways, Ireland looks fairly secular today, more like any other northern European country than the religious exception it used to be. But most people say that these looks are deceptive, and that under the surface there is a lot more going on than that. Interviews for this project regularly made the complexity of the situation very clear. Catholic influence is not apparent until it suddenly and clearly is, such as when the Angelus comes on RTE television at 6 p.m.

Young families still bring children to be baptized. A church burial is important even for those who seldom attend Mass. The choice of venues for weddings is often described in terms of choice (In 2023, 35% of Irish marriages were held in churches, down from 91.5% in 1994), though today that choice sounds much more consumerist and less existential when people describe it, a casual a matter of preference or choice: civil or ecclesial, hotel or church.10 The language of preference and choice pervades many of the interviews that went into this project, even among those who remain demonstrably committed to practice of the faith. One could also note, though, that the language of private choice certainly makes sense as a strategy to cope with the situation after the abuse crisis revelations, by decoupling faith practice from commitment and thus not making a person look still gullible for showing deep commitment to the rituals of the ecclesial authorities.

All interviewees spoke about indifference among the youth, though there were of course many committed Catholic exceptions. One example of the situation among youth may help. Parishes pool their resources in youth ministry, since most parishes had too few involved youth to go it alone. At the October 2013 semi-annual Dublin Archdiocese-wide teen event, on a Friday night, fewer than 100 youth were there, in a diocese of 1.15 million people. Half of the attendees were ethnically non-Irish, from immigrant families. One youth said that she was proud of her and her family’s faith commitments, but wouldn’t tell her other friends she was there.

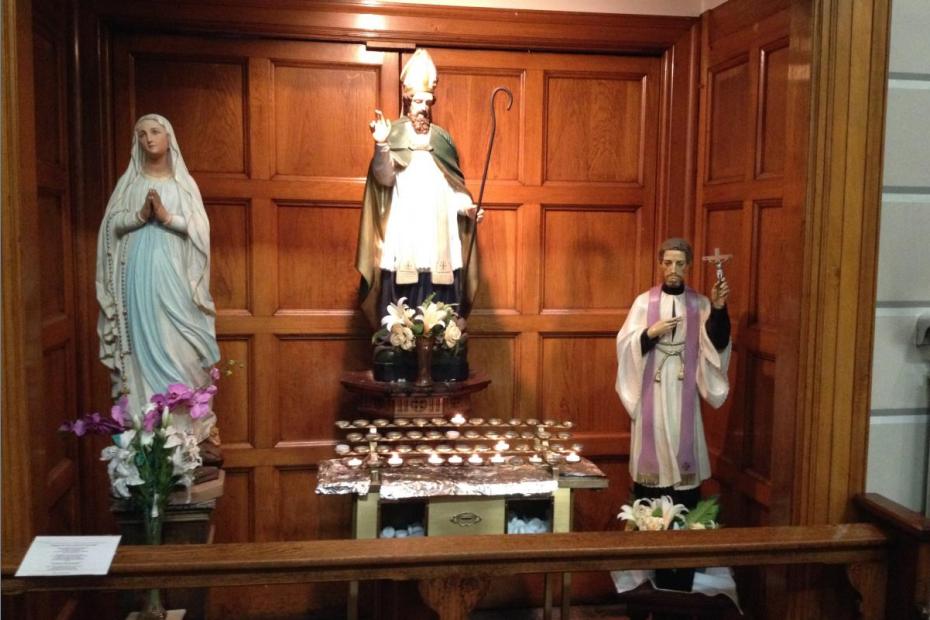

Many of the devotional qualities of Irish Catholicism endure today. Pilgrimages to Knock, Lough Derg, or Croagh Patrick can draw significant numbers of people. People frequently go up to light a candle to a favorite saint after communion, often, one told me because people have so many struggles and they need a favorite who is looking after them. “You feel when you light your candle and you say your prayer like you are talking to them [the saints]. And you do get something.” Many retain strong devotion to Mary and travel to Lourdes or Fatima.

Interviewees for this project asserted that there was easily a problem with devotionalism, and that the mark of a real Christian is measured by simple ways that one person cares for another, and doing no harm. Yet all those people talked about how helpful a particular devotion is to them. The example of one spoke for many others: “There’s one saint I actually adore. Why, I don’t know. It’s St. Theresa. I always call her me pal. All my life I say, ‘Please St. Theresa,’ and she’s always come through for me. But then, is she there? I don’t know. But she comes through for me. So she would be me pal.”

In a current context where doubts about the clergy run strong, personal devotions may well continue to have an especially important place providing the faithful with still trustworthy, quiet channels to the divine. In those ways, Irish Catholic life can still be said to be active, even though not disciplined in the old ways.

As that comment shows, to listen to almost every Irish interviewee for this project, and to read carefully many important writers about Irish Catholicism, is to encounter deep contradictions. One Irish priest, hearing a few of these accounts related anonymously, responded, “Logic and consistency are not important now in terms of religion.” He meant that not as a critique, but as a description, and a reminder to himself that logic was not yet going to fix the situation.

Tom Inglis, a prominent student of Irish Catholicism, has maintained that such churchgoing and devotional practices are now, for the average person, “occasional rather than regular.”11 On the other hand, in later work, he has written, “The Church is still at the heart of Irish cultural life… Being Catholic is a part of most people’s cultural heritage. It is a way of being in the world, of understanding themselves, that they are happy to accept. While Irish Catholics may no longer be deeply immersed in the Church, the teachings of the Church are deeply immersed in the sense they have of themselves, the way they present themselves in everyday life, the way they relate and communicate with others, and their sense of humor.”12

Recent academic social surveys claim that either 50% or 34% of self-identified Irish Catholics claimed to pray every day. 45.8% said that they had no doubt about God’s existence, 24.5% said that while they had doubts, they do believe in God, 2.7% were atheists and 4.3% were agnostic. Slightly more than 83% “definitely” or “probably” believe in life after death, 87% in heaven, 58% in hell, and 71% in miracles. But as is true in many other globalized societies, some self-defined Catholics also embraced non-Catholic beliefs. Almost 32% “definitely” or “probably” believe in reincarnation, and almost 27% "definitely" or "probably" believe in nirvana.13

Major bookstores in Ireland carry reasonably large selections of thoughtful books on Catholicism and theology, and on popular saints like Padre Pio. These are right next to large shelves that indicate significant interest in Thich Nhat Hanh and Eastern topics, and even larger selections on astrology. Still, formal religious switching has been minimal. Few have “gone over” to Protestant churches, fewer to Eastern religions. “Marginal” and “out” are the choices, but at least in terms of nominal affiliation, relatively few have taken full “out” route from Catholicism. Instead, many seem to be culturally grounded dabblers.

Catholic But Not Religious?

One of the clichés of American religion is that so many people describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious.” In interviews for this project, that phrase never came up. What did come up, both in many informal settings and in formal interviews, was effectively that many Irish under age 60 are “Catholic but not religious.” The phrase applies to a wide range of people who claim not to be religious, but then went on to describe a whole set of practices and cultural references that are part and parcel to a Catholic worldview.14

Excerpts from one interview with “Claire,” which can be heard on the link on this page, make clear how difficult it is in contemporary Ireland to draw any simple conclusions about secularity. Even as she draws on new age spirituality and claims not to be religious, her worldview is largely framed in Catholic terms. In a single conversation, her description of her own beliefs and practices exemplify many of the paradoxes repeatedly encountered in conversations with seemingly religiously indifferent Irish people.

Significant numbers of Irish who are institutionally Catholic but struggle with their doubts, such as “Kathleen,” whose interview is partly excerpted here. She makes clear how firmly she is a product of a cultural/religious past, even as she repeatedly critiques it.

Many other Irish are certainly more indifferent, and others certainly maintain strong connections to the Church and faith no matter what.

Given the multiple contradictions of Irish Catholicism today, where ecclesial authority has suffered badly, it may be fair to say that Catholicism is, in different moments and people, embedded but liminal, influenced by global change but still culturally particular, devotional but secularized, Catholic but not religious.

- 1Dermot Keogh, “The Catholic Church in Ireland Since the 1950s” in The Church Confronts Modernity: Catholicism since 1950 in the United States, Ireland and Quebec ed. Leslie Woodcock Tentler (Washington: Catholic University, 2007) 124.

- 2Central Statistics Office, 2016 Census, chapter 8, "Religion".

- 3Lawrence Taylor, “Crisis of Faith or Collapse of Empire” in The Church Confronts Modernity: Catholicism Since 1950 in the United States, Ireland and Quebec ed. Leslie Woodcock Tentler (Washington: Catholic University, 2007) 157.

- 4 Interviews with eight Dublin-area Catholics, formal conversations with 20 adult Catholics, either with groups or individuals, and visits to five parishes, were all conducted in October 2013.

- 5Though this observation always occured in interviews in the context of awareness of the sexual abuse scandals, it is worth noting that Lawrence Taylor described twenty years ago a tendency among the Irish to be "pulled inexorably by deeply rooted emotions, encompassing everything from uncritical reverence to blinding resentment." Laurence J. Taylor, Occasions of Faith: An Anthropology of Irish Catholics (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995) xiv.

- 6Staunton, Enda, “The Forgotten War: The Catholic Church and Biafra (1967-1970)” History Ireland 8 (3) 2000: 44.

By 1922, 26 overwhelmingly Catholic counties of the south and west were established as the Free State (later Republic) of Ireland, while the six majority Protestant counties of the northeast remained (and still remain) part of the United Kingdom. (This article refers only to the Republic of Ireland. The northeast counties surely share many characteristics, but will need to be treated separately at some point). In its 1937 constitution, the state accorded the Church “a special position” in the country, allowing it to be deeply involved almost every aspect of Irish life and politics for decades.

The Catholic National Schools, begun in the 19th century and run through church-state collaboration, dominate education. Even at the turn of the 21st century, Tom Inglis writes, the “vast majority of Irish Catholics have been educated by the Catholic Church… Of the 3,500 National Schools in the Republic of Ireland in 1984, 3,400 were under Catholic management.”

Tom Inglis, Moral Monopoly: The Rise and Fall of the Catholic Church in Modern Ireland (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 1998), 58-59. For an in-depth look at the institutional structure and depth prior to the 1990s, see chapter 4 in the same volume, “Power and the Catholic Church in Irish Social, Political and Economic Life.” - 7Dermot Keogh, “The Catholic Church in Ireland Since the 1950s,” 99. It is worth noting that the practice of private confession has its origin in Ireland, where priests early on developed confessional manuals that detailed sins and their gradient punishments.

- 8Tom Inglis, Moral Monopoly, 2.

- 9On the centrality of devotionalism, the culture of Irish Catholicism, and the transformation in recent decades, see Louise Fuller, Irish Catholicism Since 1950: the Undoing of a Culture, second edition (Dublin: Gill & McMillan, 2004).

- 10Breda O'Brien, "The rapid rise of ‘New Age’ weddings in Ireland: How should the Churches respond?" Iona Institute, 2024.

- 11Tom Inglis, Moral Monopoly, 205.

- 12Tom Inglis, Global Ireland: Same Difference (New York: Routledge, 2008) 148.

- 13Data are aggregated in the report by Eoin O’Mahony to the Irish Catholic Bishops’ Conference, “Practice and Belief among Catholics in the Republic of Ireland: A summary of data from the European Social Survey Round 4 (2009/10) and the International Social Science Programme Religion III (2008/9)."

- 14 In a work published shortly after this entry first appeared, Gladys Ganiel made a similar point, suggesting that traditional Irish Catholicism cast a powerful, "long shadow" today, whatever good reason there may be to speak about the "demise" of Irish Catholicism. For some, she said, the Church is simply as a "convenient foil which they now define their faith against," though she found many other interviewees who thought of themselves as simultaneously, in Catholic parishes or organizations, practicing their faith while distancing themselves from the institution. Gladys Ganiel, Transforming Post-Catholic Ireland: Religious Practice in Later Modernity Oxford, 2016), 3, 5, 102.