Every year on January 9, millions of Filipinos — newspaper reports say as many as 10 million1 — gather in Manila for a procession of the Black Nazarene, or Poong itim na Nazareno, a life-sized statue of a suffering Jesus fallen under the weight of the cross, along a 6.5 km route from Rizal (Luneta) Park to the minor basilica in Quiapo. Few religious celebrations anywhere in the world can match this feast in terms of the number and fervor of devotees surrounding the procession. Attendance has grown remarkably in the last 20 years, and the route has been stretched to accommodate growing crowds. If newspaper accounts are correct, the number of Catholics attending the Nazarene feast equals, or perhaps even doubles that attending recent papal Masses in the same locale. Most Filipino Catholics consider the Nazarene statue to be miraculous, able to heal terminal cancers and other sicknesses, to grant petitions, and to help those in need.

The statue, which normally resides above the altar of the Quiapo basilica, draws crowds to that church throughout the year, packing the hourly Masses and the area around the basilica all day on Fridays and Sundays. The Black Nazarene image is brought out of the shrine for public veneration three times a year. On New Year’s Day, it is brought out to begin a novena that leads up to the January 9 feast. On Good Friday, the day most typically associated with Jesus carrying the cross, it is also revered in public. But January 9 is the feast that draws massive crowds to see and touch the statue. The event is carried live on television, and the movement through the streets creates a religious frenzy unmatched by any other religious event in the country. The procession usually takes 18 to 22 hours, and sometimes even longer. The passion over the opportunity to touch or accompany the Nazarene sometimes results in serious casualties.2

Historical background

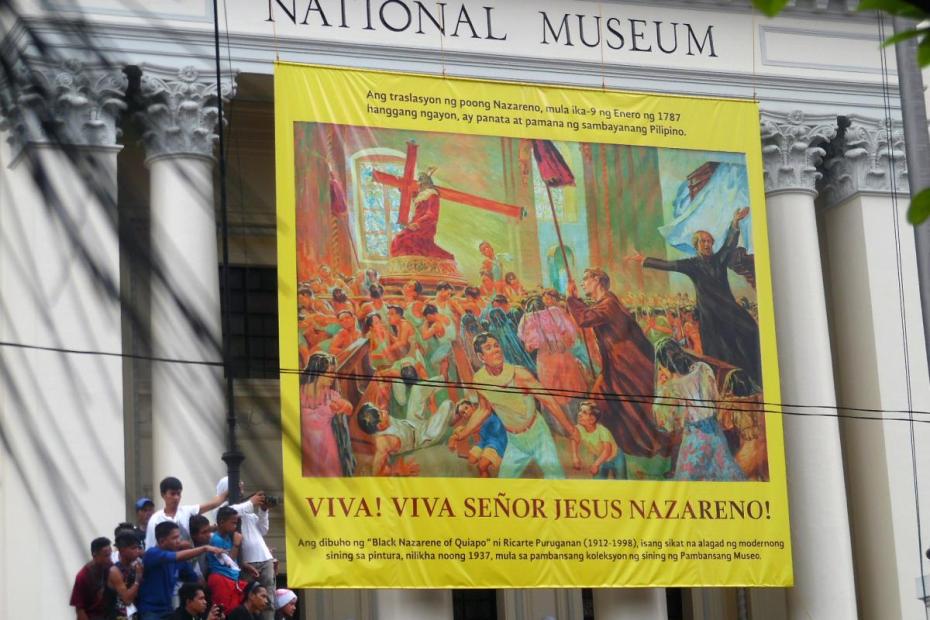

The January 9 procession reenacts a seemingly minor historical event, the 1787 solemn Translacion, or transfer, of the image from its original home, where Rizal Park is now located, to its present home at the basilica in Quiapo.

An image of the Black Nazarene, carved of mesquite wood by an anonymous Mexican sculptor, arrived in Manila in the mid 1600s. The statue was partially destroyed in 1945 during the liberation of Manila in World War II. The Archdiocese of Manila commissioned a renowned Filipino santero, or saint carver, Gener Manlaqui, to sculpt the present day replica, using the original head.

The vigil

On January 8, a million participants, mostly youth, gather in Rizal Park for a vigil in anticipation of the procession.3 Devotees line up at the grandstand for the pahalik, or “kiss,” the opportunity to kiss or touch the cross or foot of the Black Nazarene. Often they wipe the cross or foot with a cloth that they keep and rub on themselves or give to relatives unable to visit the Nazarene. The touch of the cloth is said to bring physical healing. Many groups or families bring copies of the Nazarene statue — some quite large — and other statues. These are treated with great respect and often wiped with a cloth, but do not draw the same level of frenzy as the primary Nazarene statue that is pulled in the procession.

The vigil is filled with singing, dancing, and stage plays. Inspirational talks by clergy and bishops encourage impious or wayward people, especially youth, to turn from bad habits and vices such as smoking, drugs, drinking, and pre-marital sex, to became ardent followers of Christ. Youth are encouraged to engage in apostolic-religious work like studying, preaching and teaching the gospel, and feeding street people.

The vigil continues many of these same activities long into the night. Participants sing religious and inspirational songs and dance all night long, perform and watch stage plays until the wee hours of the morning.

Devotees camp out with their own statue of the Black Nazarene at the overnight vigil preceding the procession. January 8, 2015. Photo by Arnulfo Fortunado.

The Translacion

On January 9, after a huge morning Mass, the Translacion procession of the Black Nazarene from Rizal to Quiapo begins. The Black Nazarene is moved from the grandstand to a special carriage to begin the long, slow procession, which is anything but somber. The most determined devotees walk the 6.5 km route barefoot from Rizal to the Quiapo minor basilica as penance and an emulation of Jesus on his way to Golgotha. The act of walking barefoot is a panata or vow of sacrifice and thanksgiving to mimic Christ who carried the cross to Calvary barefoot.

Other attendees lining the roads include families of the walking devotees, local and foreign tourists, devotees from overseas, and members of lay associations throughout the Philippines. Each of the associations carries a banner indicating its name and location. The banners are usually colored maroon or white and embroidered in gold with an icon of the Nazareno and the name of the association in white or gold surroundings.

Traditionally only men were allowed to be namamasan, the barefoot men who pull the wheeled carriage using two large ropes. Recently, though, women have also been allowed to pull the rope. The right side of the rope or the right shoulder was traditionally believed to be the most sacred side since it was the side on which Jesus bore the Cross.

Hijos del Nazareno, Sons of the Nazarene, clad in yellow or white shirts, form an honor guard for the Black Nazarene and serve as marshals. They are the only ones allowed to ride on the carriage for the duration of the Translacion. They help devotees to climb up on the carriage to touch the Nazarene or the cross, and they wipe the image with towels and handkerchiefs tossed at them by devotees. Wiping cloth on the statue is believed to “rub off” the miraculous power and curative abilities of the statue onto the cloth.

As devotees chant “Viva, viva," and call to the statue, the procession wends its way very slowly through the streets, able only to move slowly because of the frenzied crowds who descend on it, and usually makes it to the church late in the night.

Devotion to the Nazareno is especially strong among the large number of poor Filipinos. Poor people comprise the majority of devotees at the feast and have an especially deep devotion the Black Nazarene as a way of identifying their own struggles with the Passion, death and resurrection of Jesus. Filipino clergy variously describe the devotions as magic-oriented or mis-focused, or as admirable, pious reflections of faith, but the bishops are always eager to be there for Mass.4 In numerous ways, they try to channel this devotion through focus on the Eucharist. Whatever these efforts, the devotionalism of Filipinos seems to be growing, especially as it is manifest in burgeoning participation in the Black Nazarene feast.

In its qualities of suffering, patience, and fervor, the ritual of the vigil procession enacts the sufferings and patience of the Filipino people. While devotees bring their own personal concerns and sufferings to the Nazarene, the celebrations are an extraordinarily communal, rather than individualistic, form of devotionalism. Though Filipinos can and do visit the statue all year long, the procession is a huge event. The vigil and procession are characterized by both patience and urgency, a manner of taking things directly to Jesus walking among them, yet doing so in their own fashion. Long decades of corruption and persistent dirty politicking in the Philippines had caused enormous poverty, abuses and sufferings among its populace, and contribute to the sense of needing to turn directly to God for relief. Filipinos are patient, tolerant and forbearing people. They can take so much abuse and sufferings just like Jesus did during his passion, crucifixion, and death on the cross. Similarly, Filipinos show how they can identify by enduring a procession lasting up to 22 hours.

- 1http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/343225/news/metromanila/10m-people-join-peaceful-nazareno-festivities-no-deaths-major-injuries Other articles suggest that there are 5 – 15 million attendees.

- 2In 2015 one of the Hijos del Nazareno honor guard riding the carriage suffered a heart attack and died during the Translacion. Another devotee was declared dead on arrival at the hospital after suffering from bruises, contusion and wounds at the arrival of the statue inside the minor basilica of Quiapo.

- 3Descriptions of the vigil and feast are based on participant observation at these events in January 2015. On the crowds at the vigil, see http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/401049/news/metromanila/quiapo-church-1m-devotees-attended-pahalik-87-treated

- 4Compare the comments in Odi De Guzman, Black or White: The Nazarene and the Pinoy devotion with the Quiapos pastor’s assessment in the parish’s video on popular devotion.