Catholics are a small minority in Norway, a country with high levels of nominal religious affiliation, but low levels of religious practice. A variety of forces are altering Norway’s sense of itself and creating space for Catholic life and practice in a more multicultural society, even as immigrant Catholics and their children adapt to or contend with cultural norms that are important to Norwegian identity. In 2017 the Norwegian Lutheran Church, which had been a state-sanctioned institution for nearly 500 years, formally separated from the government.

Bergen, Norway’s second-largest city, is a compact port city on the Atlantic coast surrounded by mountains, fjords and the sea. The Catholic Church there is comprised of a single parish, St. Paul, which serves 17,800 parishioners in a territory that stretches about a six-hour drive from its southern to its northern boundary. 1 About 70 percent of the parish’s members live within a one-hour drive of the church.

Surprisingly, in a city close to the northern periphery of the world — indeed, often perceived as beyond the periphery of the Catholic world — St. Paul’s stands out as probably one of the most diverse Catholic parishes in the world. Some of the world’s major cities are home to a similar or even greater diversity of Catholics, but it is not clear there are any other places in the world that combine such diversity in a single parish. Parishioners come from more than 100 countries, but national groupings of Vietnamese, Sri Lankan Tamils, Filipinos, Eritreans, Poles and Lithuanians, and regional and linguistic groupings of Spanish speakers, French speakers and sub-Saharan Africans, define parish life.

Given that ethnic Norwegians constitute perhaps five percent of the parish, it is difficult to tell the story of Catholic life in Bergen by simply distinguishing the “Norwegian Church” from the “immigrant” Church, though this is part of the story. The church in Bergen is self-consciously multicultural. To stand in the parish courtyard, or at school, or at most Masses, is to see that diversity fully on display over and over again.

A second, very surprising aspect of life in the church in Bergen is that despite the fact that people describe the larger culture there as very secular, and say that many ethnically Norwegian Catholics also do not attend church as frequently as in the past, the overall sense of the Catholics interviewed there is that whatever their daily challenges, they are part of a local church that is vital and growing. The size of the community has grown four- to fivefold since the beginning of the millennium. Migration is the source of the vast majority of the growth, but even the number of Norwegians is said to be growing modestly. The many Masses on Sunday are packed, and the school and parish are always abuzz with activity throughout the week. Groups compete for space in meeting rooms in parish buildings.

As of June 2015, the parish reported membership of about 17,500, including registrants born in more than 100 countries. This includes 6,896 Poles; 2,277 Lithuanians; 920 Filipinos; 348 Sri Lankans; 304 Vietnamese; 219 Germans; 187 Slovaks; 174 Burundians; 124 Brazilians; 98 Eritreans; and 3,631 Norwegians.2 The “Norwegian” figure includes Norway-born children of the other ethnic communities. Hence, while there may be 304 members of the community who are listed as “Vietnamese,” when the whole community gathers, including their children, there are said to be as many as 700 people. The newly ordained “Vietnamese” priest, Fr. Bjørn Tao Quoc Nguyen, is actually Norwegian-born and counted as Norwegian in the above figures. The Polish, Lithuanian, Filipino, Sri Lankan, Vietnamese and Eritrean communities all have their own priests and activities within the parish.

Historical background

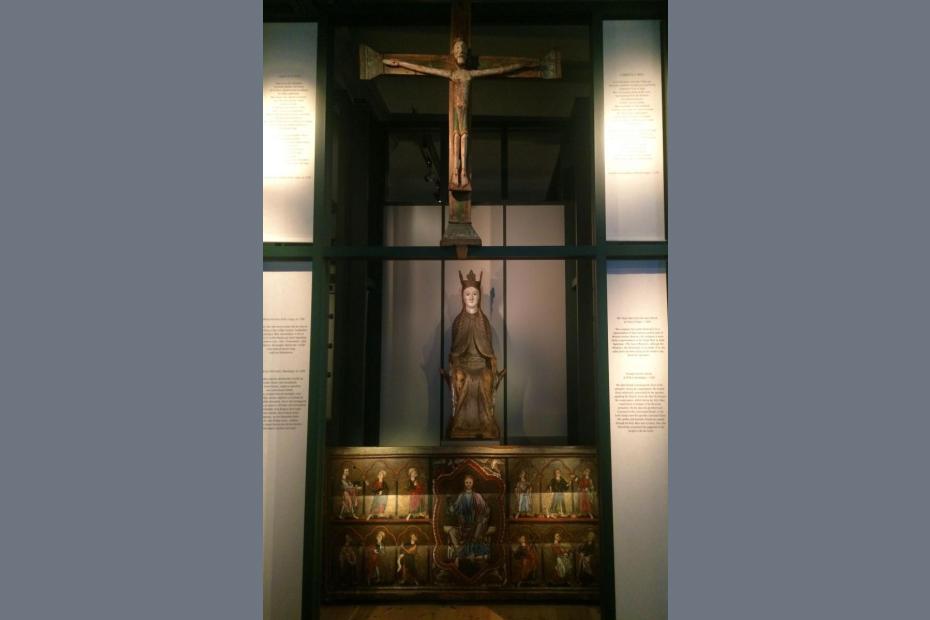

Catholic Christianity is known to have reached Norway before 1030 AD, when it became the state religion under King Olaf II, canonized as Saint Olaf, who still serves as Lutheran Norway’s patron saint. Norway lost half its population during the plague of 1349, and the monasteries, which were central to Catholic life, were crippled and never fully recovered. The Danish crown, which ruled Norway, embraced Lutheranism as the state religion in 1536. To some degree, this entailed taking monastic lands more than real theological conversion. Indeed, a trove of art and religious objects in the Mariakirken, the church that is the oldest building in Bergen, and at the historical museum at the University of Bergen bear witness to enduring Catholic religious imagery in Protestant churches. Still, by the 18th century, the country was clearly Protestant in terms of polity and allegiance. The 19th century saw the introduction of a strong, sometimes harsh, pietist movement that reshaped Protestant culture, but the same era saw the beginnings of religious tolerance, and Catholic practice was again legalized. The first Catholic parish opened in Oslo in 1843.

Bergen’s Catholic community was founded in 1858 for two Catholic families. The present church, St. Paul’s, was completed in 1870 and was largely funded by German Catholics as a missionary endeavor. The 300-seat church, though small for the parish today, was an act of hope, or perhaps hubris. For many years, the Church’s self identity is said by older interviewees to have been built on the romantic and nationalist notion that it was Catholics’ destiny to restore Norway to its original religious and cultural heritage. Norway had for hundreds of years been under Danish, and then Swedish domination, and local cultural and political leaders tried hard to shape a specifically Norwegian national identity both before and after Norway finally achieved political independence in 1905. Catholicism’s rebirth was both challenged and framed within that highly nationalist context. Parishioners recall even in the 1950s and ’60s singing “Norwegia Catholica,” about Norway’s Catholic roots, and how the country would find its most authentic self when it was again made Catholic.

Catholicism grew slowly but continuously in Bergen in the 20th century, to include perhaps 500 believers in the 1950s. Much of that growth was aided by a trickle of immigrants from other countries. A Norwegian religious order, the Sisters of St. Francis Xavier, comprised largely of foreign missionaries, played a huge role in the church in Bergen. “When you go back to the 1930s,” an older Catholic said, “about a third of the Church was made up of nuns. They ran everything.” They established a hospital, now closed, and a school that continues to thrive.

Changing national identity

Until the 1960s, Norway’s sense of itself was as a very poor, peripheral land, dominated by other countries. Until the mid-19th century, identity was local, defined by local dialects and costumes in valleys often isolated from each other. Some degree of that sense of local identity still exists, and is manifest in local traditional costumes that ethnic Norwegians receive as a coming of age passage, and wear on the national holiday.

Since the late-19th century, Norwegian culture was rebuilt as a “unity culture,” a political-cultural effort to unite those local identities through one church, the Church of Norway, one king, one language, one culture. Baptism and confirmation were two of the important rituals that affirmed membership in that unity culture. Until the 1980s, there was only one television station, whose mission was to provide Norwegian programming that built Norwegian identity. Public schools were an important mechanism for national unification, and those who did not attend them were viewed with suspicion. Older Catholic interviewees recalled that there was a sense that to be Catholic, and specifically to attend Catholic school, meant, as public schoolchildren told them, that they could never really be Norwegian.

The 1970s saw the beginning of oil and gas production in the North Sea that has radically changed Norway’s situation, turning it into one of the most prosperous countries in the world. This wealth brought Norwegians out into the world, and set the stage for the immigration that is reshaping Norway today. Many refugees, beginning with Chileans and Vietnamese, and later including larger groups of Tamil Sri Lankans and Eritreans, came to escape political oppression. As the economy boomed and many kinds of jobs could not be filled locally, others came for primarily economic reasons, including Filipinos and recent large groups of Poles and Lithuanians.

Norway has moved away only slowly from using the Church of Norway as a source of national cultural and political identity. In 2012, the constitution was amended so that the government no longer appoints Church of Norway bishops. Yet the state still plays a significant role in the life of the churches. The royal family still must be members of the state church, and the monarch serves as its head. The state is the source of revenue, through taxes, for the state church and all the churches. About 80 percent of Norwegians still belong at least nominally to the Church of Norway, and for the allocation of revenues, the government still presumes a resident (even an immigrant) belongs the state church, unless he or she registers in another church. Unlike Denmark or Germany, the tax is not added to people’s tax bill, but is taken from the taxes all people pay anyway. Religion, particularly Lutheranism, but also world religions, is taught in public schools, not from a faith perspective, but often with a goal of fostering national identity, ethical values and global cultural awareness. The state does, however, help fund the Catholic Church as well, in proportion to its membership, and now provides funds for Catholic schools with a religious mission.

One significant change over the last several generations, not unusual in countries that have state churches, is that overall religious practice in Norway has often become often a matter of “belonging without believing.”3 Many Norwegians speak about a gradual secularization of their culture, but church membership remains relatively high. According to the Pew data, fewer than 10 percent of Norwegians are religiously unaffiliated.

Cultural contexts of Norwegian life

Catholic interviewees in Bergen offered a mixed assessment of the state of religion today in the country. They described a culture that, in their experience, still at least symbolically and reflexively looks to the Church of Norway for its identity. They told stories of work colleagues and peers who were deeply uncomfortable about public talk of religion: “We are much more comfortable talking about sex than religion,” several said. But several also echoed the comment of one person, “When you scratch under the surface, Norwegians do believe in God. It’s just that they seem to be deeply uncomfortable talking about God.” The norm for the Church of Norway, they say, is to visit four times in one’s life: for baptism, confirmation, marriage and one’s funeral. Few people, they say, express real hostility to religious practice. Some identified remnants of anti-Catholicism in Norway among free church members, but interviewees who had talked about their faith with non-believing or non-Catholic Norwegians repeatedly said that they felt listened to and respected, not belittled. One man reported that his conversion to Catholicism met no hostility, but sometimes puzzlement. He saw indifference as the key cultural situation, having morphed as “tolerance that turns into indifference.” An immigrant woman, whose husband’s family belongs to the Church of Norway but does not practice, said that family and social norms often meant that she had to push back harder than she should to extract herself from family events to go to Mass.

It is important to note that the tendency toward privacy in Norway is not solely in the context of religion. Catholic immigrant interviewees regularly emphasized reservedness, privacy, modesty and egalitarianism as key qualities of Norwegian life. They often admired the degree to which it is a society with little corruption and a strong ethos of fairness. Norwegians were characteristically more modest about claiming these qualities, but said that they hoped these were true. One Norwegian did say it is “not in Norwegian culture to be open.”

A visitor to Bergen would easily come away with the impression that it is a beautiful but very modest city, a place where a number of churches are visible but that red light districts, if they exist at all, are not. Neither does one see the high-end clothing or jewelry stores that one would often see in other high-income countries and tourist areas. Bergen looks like a city that is modestly prosperous, but doesn’t feel like a city that is nearly as wealthy as it is.

Interestingly, foreign-born Catholics often talked about Norwegians’ modesty and discomfort with any form of showing off materially or parading social status. Clothes are modest, and jewelry and flashy displays are frowned upon. One interviewee remembered the disapproval that she saw over her sense of style, with high heels and matching handbags. Norwegians, when asked, worried that they were too showy and materialistic. The latter perspective need not negate the former, of course, and might even confirm the same perspective via the expression of their discomfort with material showiness. Certainly by many cultures’ standards, Norwegians in Bergen seem quite averse to showing off wealth.

Asked “What does it mean to ‘become’ Norwegian?” native Norwegian Catholic interviewees were hesitant to ascribe special cultural values to Norway, the way an American might cite freedom and self-reliance as American traits. They avoided any characterizations that might be seen as exclusive, and focused on what they saw as baseline qualities: being able to speak the language, to work and contribute to society, and to commit to have one’s children identify with Norway’s future. One cited a 19th-century Christian pietist aphorism, “You have to work, then you can eat!” and a labor aphorism, “Do your duty, protect your rights” as still descriptive of Norwegian character. Interestingly, most people resorted to activities — love of hiking and skiing — describing Norwegians by things they do rather than values they share. This was not a consumerist mindset, whereby people’s identity derives from what they consume, but it was defined by shared activities in a natural setting. Some referred to closeness to nature and to egalitarianism as typical, if not definitive, cultural traits, but hesitated to say anything that seemed exclusive or somehow smacked of a sense of cultural superiority.

A number of themes surfaced during interviews about the implications of these cultural traits for Catholic practice.

Not surprisingly, interviewees mentioned that Norwegians are ill at ease with religious display of crosses, religious jewelry, etc. Many Catholics said that they were not allowed to wear religious symbols in the workplace. Catholic culture was often still very material, though. Many Catholics pulled out an image of a cross or a Rosary or the Virgin of Guadalupe that was kept in a pocket or a backpack. One wore a St. Brigit’s cross, because “people don’t even know what it is, and think it’s just decoration.” Others had religious images in their homes. On the other hand, one of the parish’s key annual events, a Corpus Christi procession through the streets, violated all these norms.

Norwegian cultural norms limit the involvement of young people in the Catholic Church. While the school and youth groups and altar service provide opportunities to engage children and youth in the church, many parents reported that their adult children tended to drift away from practice once that was over. Not enough time had elapsed for these interviewees to know whether those children would come back when they married.

Norwegian character, particularly the sense of equality and fairness, impacted Catholic religiosity in another interesting way. In many countries, religious people argue that religion is important because it ensures that society is fairer and people are more ethical. For Norwegian Catholics asked about this, Catholicism was less about finding an ethical anchor. Theirs is already a low crime, low corruption, low poverty society. “You don’t have to be religious to be a good person,” said one, “but it can make you a better person. Many people in Norway are good people, but are not religious.” He suggested that for him, Catholicism was about adding love to the equation, not just obligation to share. “Learning to love other humans is central in the Catholic faith. Being Catholic makes us more conscious of suffering in the world, more conscious of charity.”

Norwegians’ sensibilities may also have helped to prevent any real culture wars. Migrants and others liked living in Norway and were grateful for the opportunities it provided them to work and lead good lives. They were hesitant to hold themselves against Norwegian society, except to identify some of the issues mentioned above, and to express their concern about issues like abortion, the possibilities that churches might bless same-sex marriages, and the frequency of divorce. But even where they expressed concern for this, they did not talk about themselves as persons who somehow had to be holdouts against a corrupt and declining culture. They expressed their perspectives through the ordinary political processes, and except on abortion, tended to make their peace with the collective will of the society on legal matters.

In these ways, Catholics were more conservative than other Norwegians, but not in the neoliberal sense. More politically inclined interviewees noted that libertarianism was creeping into Norwegian political life, and rejected that brand of conservatism. They wanted a society that is more egalitarian in terms of distribution than libertarians want. Perhaps not surprisingly, they were eager to welcome newcomers who wanted to fully join Norwegian society, even if they worry about how Norwegian society can absorb so many more people today. Several interviewees, including native Norwegians, volunteered to help immigrants assimilate, get educated, and find jobs at organizations like Caritas.

Norway’s wealth, as was said earlier, has transformed the country. Economic prosperity is often described as naturally corrosive to religiosity, but interviewees in Norway generally did not seem to think that it was problematic for them, or that Norway’s wealth made it a harder place to be a good Christian. Problems from wealth were perceived to depend on greed or on radical inequality, both of which are relatively mitigated in Bergen, even as prosperity is broadly felt.

Converts

When it comes to Norwegian Catholic life, the Church is shaped in many ways by the fact that most ethnic Norwegian Catholics are converts. Even the bishop and the pastor at St. Paul’s are converts from the Church of Norway. Some had journeyed from the Church of Norway to other Protestant denominations before becoming Catholic, and described having been very active in those churches. In those instances, most said that the Church of Norway had changed too much. Overwhelmingly, they were drawn to a liturgical form of prayer, and some saw the Catholic Church’s growth as evidence that the Church was doing something right. Equally, they said that they thought that Catholicism had a deeper respect for Christian tradition. The litmus test for how the Church of Norway had gone “too far” was never around ordination of women, but almost always around the possibility of “homophile” marriage in the churches. Some also said they were drawn to a sense that “true” Norwegian identity, in historical terms, is Catholic. Some talked about finding a greater breadth of spiritual resources in Catholicism, such as praying from the liturgy of the hours. One was exposed to these through an ecumenical retreat movement that draws on these resources.

When interviewees spoke about the Church of Norway, the differing theological visions behind Lutheranism and Catholicism were never raised by interviewees, even at such basic levels as their different understandings of communion. Rather, people talked about the fact that the Church of Norway was a state church, as if it were post-denominational.

Many converts indicated that they had a real adjustment to make, if they adjusted at all, to Catholic thinking about the role of the saints and intercessory prayer to them; the materiality of Christianity, e.g. the scapulars that some immigrants wear; and spiritual practices and various traditions of prayer.

Other interviewees — those who were not converts — said that a significant number of converts “read” their way into the Church, having been drawn to romantic ideals of the Church, only to have difficulty confronting the actual pluralism of the Church, and the materiality and devotionalism of many immigrant Catholics, which they find foreign to the historical and theological reasoning that they've read. Many are especially attracted to the high Mass and to Gregorian chant. Some church leaders suggested that over time one half to one third of converts do not stay active in the Church, but the reasons for this were not clear.

A growing and welcoming Church

Some migrants who have been in Bergen for decades talked about arriving at a church that seemed to them to be cold, or at least very reserved, with a relatively small community at Mass. Yet interviewees consistently described something very different today, something that has surely been enabled in particular by so much immigration. Interviewees often expressed pride that in Bergen, St. Paul’s is the only church where one could regularly see people overflowing from the doors of the church. They spoke of feeling welcomed in a very diverse community, and welcomed in ways that are a bit more effusive than is often the case among more reserved Norwegians. Immigrants have brought characteristics that have clearly helped the Church stand out.

The reality in terms of church attendance is probably a bit more complicated than members describe, even if it is refreshing to see a Northern European church so full at so many Masses. St. Paul’s has six Masses on Sunday and one on Saturday evening, and seats about 300 people, with more people often standing in the back and at the doors and beyond. On the one hand, attendance is great, a problem many parishes would like to have. A quick bit of calculation makes clear, though, that this attendance could only account for about 11 or 12 percent of the Catholic population in church on a given Sunday.4 Perhaps 30 percent of parishioners live more than an hour away, and the priests do go out to visit small communities regularly. It was even said that the church encourages Catholics living far from a Catholic church to at least attend a Protestant church, though not to receive communion. One interviewee admitted, when asked about the numbers, that perhaps 50 percent of Catholics attended less than once a month, plus Christmas.

A regular, but not weekly, attendee who was involved in other ways in church life, suggested that in the old days, with fewer Masses and a smaller parish population, one’s absence could be noted. Today, it’s hard to know who went to a particular Mass. He also suggested that many of those who were less regular attendees were likely to center Christian life more on social and charitable action than liturgy.

- 1The articles presented here are based primarily on interviews conducted in September 2015 in Bergen with 20 Catholics and one member of the Church of Norway. Interviewees were evenly split between men and women. Fourteen were immigrants, and six were native Norwegians. Most Catholic interviewees were very active in the parish. An original version of this article cited the September, 2015 number of 17,500, but that has grown to 17810 as of May 2016.

- 2Figures courtesy of St. Paul’s parish council, based on a June 2015 count of church members as a follow-up to a scandal that deeply embarrassed the Catholic Church. The Church was accused of padding the numbers of Catholics. Persons who did not belong there were found listed on the rolls that determined government subsidies to the Catholic Church. Persons of Latin-American heritage were apparently presumed by the Church to be Catholic, but other names found their way on as well. The legal case is unresolved as of September 2015, but the church has had to fully reexamine its membership, and indeed found many Catholics who were not officially registered. The government system still presumes persons to be part of the Church of Norway unless they register as Buddhists or Catholics or secular humanists or members of any other chosen religious or ethical group. Some groups, like Poles, are still said to be under-registered, not understanding why, if they are baptized, they should have to register with the state to be “members.” The parish's May, 2016 count is 17,810.

- 3The phrase was popularized by the British sociologist Grace Davie to characterize belief in a number of European countries. See Grace Davie, "Introduction" in Religion in Modern Europe: A Memory Mutates (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 3.

- 4It bears noting that almost all the interviewees for this project were weekly church attendees, which requires us to at least ask what sort of voices or perspectives were missed.