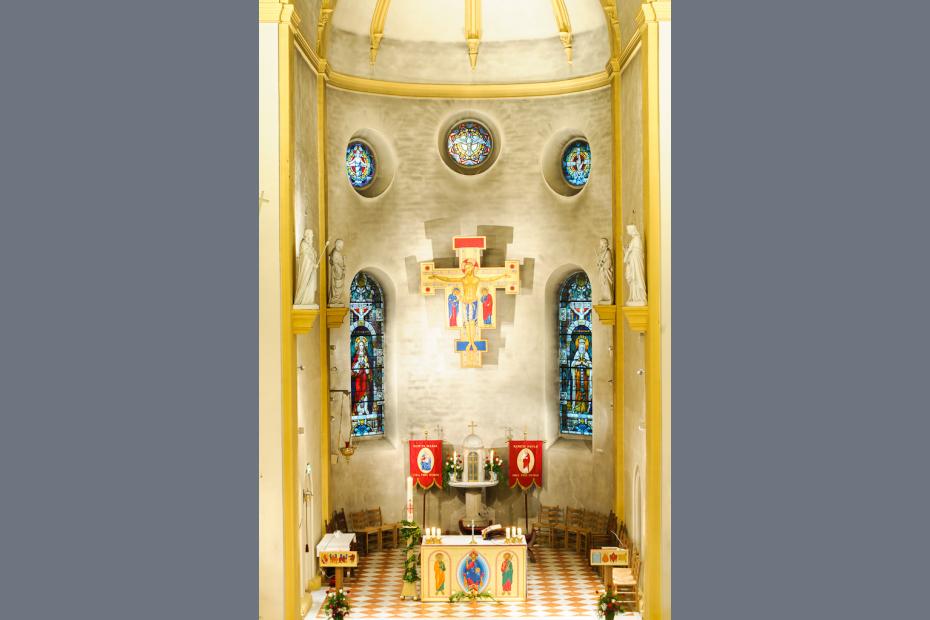

St. Paul’s Church in Bergen prominently features a colorful San Damiano-inspired cross above a radiant gold altar fronted with images of St. Peter and St. Paul flanking a seated Christ 1 Christ and St. Paul are among the images in the windows. High above the nave, plaster statues of the twelve apostles, painted white, look over the church. In a sense, these saints, who disappear into the background or at least lose their individuality, may most successfully symbolize the place of the saints in Norwegian lay Catholic life.

Among interviewees in Bergen,2 a number of immigrant Catholics said without hesitation that as good as Norwegian Catholics were in many ways, they had little understanding of the Virgin Mary’s motherhood and her love and protection for us.

Several Norwegian converts indicated too that they had a real adjustment to make, insofar as they adjusted at all, to Catholic thinking about the role of the saints and intercessory prayer to them; to the particular materiality of Christianity, e.g. the scapulars that some immigrants wear; and to spiritual practices and various traditions of prayer as part of Catholic life. Low church Norwegians critique that materiality, even as it is clear that it was very much a part of Norwegian Christianity for many centuries.

One Norwegian convert reported that she had been given a miraculous medal but admitted she still did not understand it spiritually or affectively, though she hoped she would grow in her understanding of it.

Another said that he liked the focus on saints, but clearly saw them as guides, role models or examples, not intercessors. “There are so many saints that you can always find one who is applicable to you. I have a devotion to St. Therese of Liseux… it’s her simplicity, her way of life. It’s not impossible, it’s something everyone can do. Her meekness is something I find extraordinary.”

Compared to a number of cultures, saints and images have an almost clean, untouched quality as they are imagined and described. Though St. Paul in the church window carries the sword that beheaded him, as in traditional Catholic iconography, bloodiness, sacrifice and suffering are not central to the way they talk about saints or the qualities that merit one for sainthood. Indeed, one Mexican interviewee said that she had reconfigured her relationship to suffering and pain in terms of religiosity by virtue of living in Norway. She said that her inherited focus on suffering, when it came to Jesus, Mary and the saints, had made her “fall into self pity, and I don’t like it. I don’t want that back again. I get too focused on my sufferings and my problems. It’s a common thing in my culture. We Latins have that sense of self-pity.”

In Norway, she grew to believe that if she had a problem, she needed to work to fix it, “not just feel bad about it.” “The focus in the images here is on the good things. People here work and try to solve problems.”

Saints, it seemed, were people who got out there and solved problems, who took care of others.

- 1 Both Crucifix and altarpiece are by the Norwegian Catholic artist and iconographer Solrunn Nes.

- 2The articles presented here are based primarily on interviews conducted in September 2015 in Bergen with 20 Catholics and one member of the Church of Norway. Interviewees were evenly split between men and women. Fourteen were immigrants, and six were native Norwegians. Most Catholic interviewees were very active in the parish.