On each of the nine mornings leading up to Christmas, Filipino Catholics gather in the pre-dawn hours for Simbang Gabi, a novena of Masses that anticipates the celebration of Christmas. Churches are generally filled out the doors, or the Mass is held outside to accommodate the crowd. The timing of the Mass, which begins as early as 4 a.m., helps make the event special and highlights the seasonal sense of anticipation. The experience of rising early in the morning and traveling to church in the dark adds an element of sacrifice and specialness. The experience of eating together among the crowds in the plaza after Mass, before heading to work, adds a sense of festiveness and camaraderie. Many Filipinos believe that petitions brought to the baby Jesus at each of the nine Simbang Gabi Masses are especially likely to be answered.

The Simbang Gabi tradition grew out of a practice brought by the Spaniards, who held Masses known as Misas de Aguinaldo or Misas de Gallo in December in the pre-dawn hours for field laborers in honor of the Annunciation. The tradition was discontinued in Spain and most of the rest of the world but is a vibrant practice among Filipino Catholics.

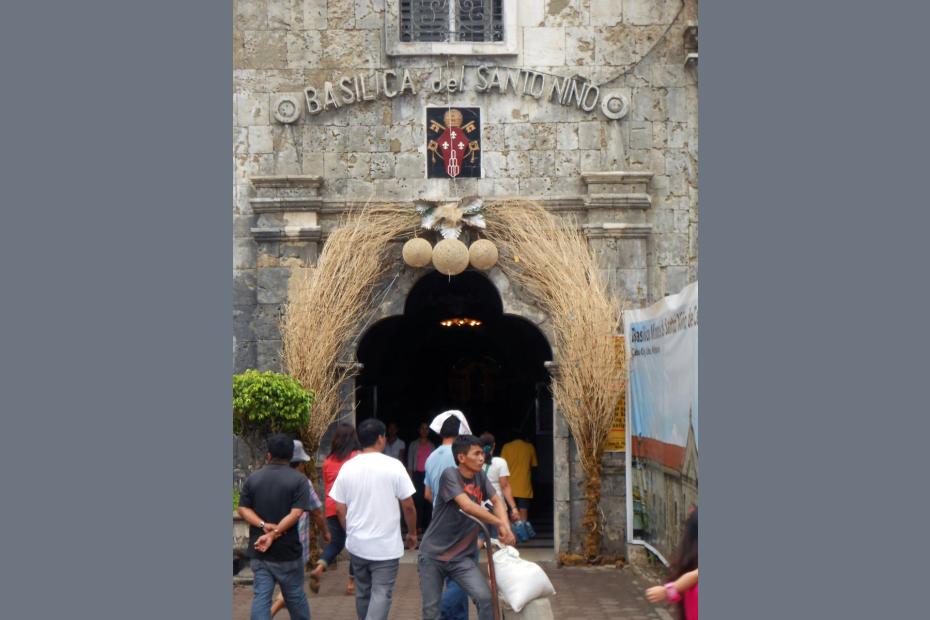

Simbang Gabi practices are fairly consistent across the Philippines, as is evidenced by observations in three provinces, Bulacan, Cebu and Davao in December 2014.1

At the Santo Niño Parish in Bustos, Bulacan, as at many other parishes in the Philippines, church bells begin to ring at 3:30 a.m., after which loudspeakers play Christmas songs to invite the churchgoers for the Simbang Gabi at 4:30 a.m., by which time the church is full. The first rows are occupied by some of the elder members of the church, in seats that are regularly theirs, while young people stand in school uniforms in the back and outside.

The Simbang Gabi Mass, which usually focuses on how one becomes prepared for Christmas, is celebrated with particular attention and style.

Examples of Simbang Gabi Masses at churches in Bulacan, Cebu and Davao.

In interviews at parishes in the three provinces, devotees gave a variety of reasons why they attended. Many young attendees, aside from pointing out that their school might expect it, stressed that it was a chance to participate in an important tradition of their parents and grandparents, and a way of unifying them with family and friends. Others described it as an important sign of respect, celebration or preparation of Christmas, the event it anticipates.

A minority echoed a traditional belief about the novena, that the sacrifice of attending the pre-dawn Masses makes it as powerful as a panata, a vow of allegiance made in the hope or expectation that one’s wishes will be granted by the baby Jesus. Panata petitions ranged from spiritual to very material, from wishes for peace and reconciliation, to protection from accidents like typhoons and earthquakes, to good health or healing, finishing studies or board exams, getting a good job locally or internationally, or even for acquiring a house.

Food is an important part of Simbang Gabi. These days are a time of incessant dining rather than fasting, and a time of family gatherings and reunions with friends and relatives, of strolling, picnics, swimming – any way that Filipino families can find to celebrate. Until the economic crisis of the 1990s, churches often served an Agape meal after Mass, sponsored by a family or a group of families, an association, or a company. It was usually composed of hot coffee and local delicacies such as various kinds of rice cakes: bibingka, a rice cake cooked in a clay pot oven, puto, puto bumbong, a rice roll made from purple rice, kutsinta, biko, and pan de sal or arroz caldo porridge. Many of these foods were labor intensive and specially associated with the season. Of the churches observed for this research, only one church in Cebu, the Archdiocesan Shrine of the Most Sacred Heart of Jesus, still serves an Agape meal every morning for Simbang Gabi churchgoers. Others often serve one for volunteers like choir members, sacristans, and lay ministers. These days, sidewalk vendors outside the churches do a brisk business by selling the traditional rice-cake delicacies, including bibingka, and puto bumbong. But some of the traditional, labor-intensive foods associated with the season are being replaced by less seasonally-particular foods like kwek-kwek (deep-fired hard boiled egg), goto porridge, and mami noodles.

- 1Maricel Eballo conducted fieldwork in Bulacan Province, while Arnulfo V. Fortunado conducted fieldwork in Cebu and Davao, all in December 2014. This fieldwork forms the basis of this article.