All countries’ forms of Catholic practice are influenced by cultural practices that predate the introduction of Christian practice. In Uganda, given the relatively short history of Christian presence, the relationship between Catholicism and indigenous practices are closer to the surface of people’s consciousness, despite the fact that Ugandan Catholic practice is also at times very startlingly European in style and image. Interviewees were self-conscious about the ways that indigenous Ugandan religious and social practices posed moral challenges to them, and also highlighted values that connected them to the practices and beliefs of their ancestors in ways that they saw as positive. Attention to aspects of the continuing impact of traditional religion should not detract from our awareness that Ugandans, especially in cities, are often as much affected by contemporary forces of globalization.

Only 1% of Ugandans describe themselves primarily as practitioners of traditional local religions, but such practices endure among many people who identify as Christian or Muslim. In interviews, Catholics always deny participating in indigenous practices on their own, but quickly tell of examples of traditional religion being practiced at night at some house in the neighborhood or at a certain rock or hilltop. Catholics speak frequently about witchcraft, witchdoctors with special powers, “Satanism” and worship of many “small gods.” Traditional practices persist, they say, especially to prevent the malevolent spirits of their aggrieved or sinful ancestors from affecting them today, and also to bring luck or fertility, to exact vengeance, and to seek healing. Indigenous rites following birth of twins, whose births were traditionally seen as a troubling omen, are also mentioned as enduring and morally problematic to Catholic interviewees.

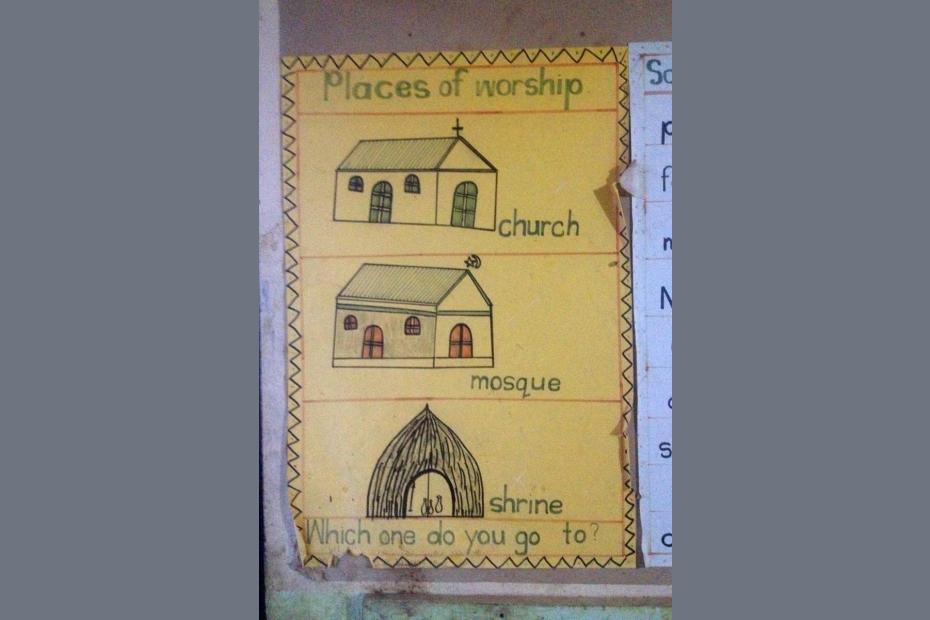

Indigenous, or traditional, Ugandan religion is not formalized in hierarchies, creeds and written sacred texts, but is a sophisticated and widely pervasive set of beliefs and practices passed down orally. The boundary between culture and religion, between past and present, between this world and the other world, is thin in Ugandan indigenous religions. The forces of the other world have to be appeased and controlled.

Traditional Baganda religion held that there was a high God, whom Christians came to understand as God the Father. Broadly speaking, local traditions about the enduring presence of ancestral spirits provide an imaginative framework that has an important place in Ugandan Catholic belief. The hand of God and the hand of Satan are regarded as active forces in the world, bringing rain or drought, but also disease. For urban interviewees, this knowledge is often partially connected to science. One said that she believes that medicine, not miracles, cure people, but went on to talk about the activity of malevolent spirits in the world. Another said that he knows that a mosquito brings malaria, but explained that the question that follows is why that mosquito bit one person instead of another.

The cult of the saints and beliefs about saintly intercession fit well within this African traditional framework, and make it unsurprising that there is such devotion to the many Uganda martyrs canonized by the Church, who serve as ancestral role models and intermediaries. Saints’ names remain particularly important for Catholics when it comes to choosing names for children, out of a belief that those saints will look over their children’s well being. Devotion to the Virgin Mary was a powerful, early feature of Baganda Catholicism, “built on the existing veneration of the Queen Mother, or Namasole, of the Kabaka, or king.”1 Mary had a logical correlative place in the religious cosmology of believers because, as John Waliggo explains, the Queen Mother “was the most effective door for those seeking royal favours. She was the ardent upholder of the purity of the nation’s traditions.”2

Religious objects, sometimes disparaged as “fetishes,” played an important role in traditional religion. Catholic sacred objects — rosaries, statues, images — easily found a role in a culture that saw (and still sees) the importance of sacred objects. Catholicism in Uganda was not brought to an iconoclastic culture, but to one that believed and believes in the possibility of prayer through religious objects, though Pentecostalists have more recently been denouncing that. Rosaries in cars are said to help protect drivers from accidents. Holy water sprinkled at home can ward off bad spirits, as can rosary beads in a bedroom. The same water is often drunk to insure health, or sprinkled in the garden to insure good harvests. The possibility of Real Presence in the Eucharist does not seem abstract or merely symbolic.

Other legacies of indigenous religion make it stand out in terms of contemporary Catholic practice. One aspect of traditional religion that clearly endures in Uganda and is seen there as consonant with Christianity is the notion of “family tree,” i.e. the biblical and traditional Ugandan notion that the sins and failings of one’s ancestors can be visited on generations to follow, impacting one’s own life today. Ugandans consistently professed a fear that the transgressions of ancestors might be the root of their suffering. Mt. Sion Bukalango Shrine specializes in healing such difficulties.

Traditional herbal medicine plays an important role in Ugandan life, including among Catholics and Anglicans, though Pentecostals condemn such practice. Traditional herbal medicine exists alongside western medicine, sometimes as a first resort, sometimes last. Healing abilities in traditional medicine are described by interviewees as being a function both of knowledge of herbs, but also of supernatural power. Some priests are said to be quality healers, and one priest, Fr. John Baptist Bashobora, has attracted a large following. But interviewees also worried that plenty of other healers were appealing to evil forces and practicing witchcraft.

Evil, curses and witchcraft are not abstractions, nor is evil only seen as a matter of personal choice. St. Gyaviira Mayanja Musoke, one of the Ugandan martyrs, is even a patron saint for those troubled by witchcraft. Interviewees suggested that in their experience, Ugandan priests did not focus on condemning traditional ways as evil, but on leading believers toward the good.

Despite the conflicts between culture and Catholicism readily and repeatedly emphasized by Catholics, Ugandans often perceived local indigenous cultures as far less challenging to Christian life than the contemporary forces of urbanization and globalization. The outcome of urbanization, many argued, is a weakening of the social bonds of rural life. Globalization brought the importation of “foreign” values, and the resultant “get ahead at any cost mentality” that was said to be undermining morality. These challenges were particularly noted when it came to family life, on issues like modesty, single parenthood and homosexuality, but also extended to enabling religious defection to Pentecostals who, they claimed, had been prevented from making inroads in rural villages, and to increasing crime.

- 1Paul Kollman, “Generations of Catholics in Eastern Africa: A Practice-Centered Analysis of Religious Change,” Journal of the Social Scientific Study of Religion (2012) 51 (3): 422.

- 2John Mary Waliggo, The Catholic Church in the Buddu Province of Buganda, 1879-1925, PhD dissertation, Cambridge University, 1976 (Kampala, Uganda: CACISA) as cited in Kollman, 2012, 423.