Located in the hills outside the city of Kampala, The Eucharistic Shrine, Mt. Sion Prayer Centre Bukalango is the hub of charismatic Catholic life in the Kampala area.

Mt. Sion Bukalango is a series of large outdoor compounds built in the hills around a small sub-parish church about 25 km from Kampala. The site hosts a number of Masses, healing services and Eucharistic adorations throughout the week, and is especially known for a weekly, six-hour service dedicated to resolving issues of “Family Tree,” the Ugandan — and biblical — belief that the sins of ancestors, both living and dead, directly undermine a family’s physical, mental and spiritual wellbeing. Believers come to Family Tree services at Mt. Sion Bukalango to be freed from the burden of those sins, and to be healed mentally, physically and morally.

Services are decidedly low-tech, bearing little in common with televangelists or stadium preachers on the technology front. Services begin midmorning in a steeply sloping field, which features an outdoor altar and Marian shrine at the top of a promontory, next to a small chapel.1 The Blessed Sacrament is exposed on the altar, “so that people could speak directly to Jesus,” one visitor noted. In their prayers, in Luganda, visitors ask for healing, for blessings, and for release from curses. Many worshippers hold up photographs of family members, not usually to pray for their protection, as at some shrines around the world, but for release: “Some people are disturbed by the spirits of the dead. So they were asking forgiveness, they were forgiving their dead people… they go through a number of deliverances,” an attendee explained.

Satan is a much felt, much discussed and visible presence at the service. The shrine’s leader, Msgr. Magembe Expedito, prays for deliverance from the ways of Satan, whether through the bonds of Family Tree, curses, from witchcraft’s effects, from evil spirits that endure as a result of our sins. In the crowd of perhaps a thousand people, 20 or more possessed women cry out and writhe around on the ground or stumble about violently. None of the visibly possessed was male. Mt. Sion did not allow videos inside its outdoor worship compounds, ostensibly because Pentecostals were coming to spread mistruths about the shrine. In an audio recording of part of the service posted on this page, hear the priest call out in English to the demons possessing people, and then call out in Luganda for deliverance of the people. Petitioners are reminded how God, through the Eucharist and through their prayerfulness, heals them from this presence.

Following that service, worshippers walked halfway down the hill to a compound for more praise and worship and for Mass. The service of praise and deliverance lasts for many more hours, with many participants able to take cover in the shade under awnings and tents. Later, too, many people come to the offices for counseling about morals and problems concerning mental illness and possession.

Though one can find many signs of traditional Catholic devotion at the site — statues of Mary, and even the name, “Eucharistic shrine” — the centre stands in contrast in a number of ways to a Marian shrine like Kiwamirembe. Twenty-five years ago, such a site, and its forms of worship, would have had no place in Catholic life in Uganda. Today, however, with the rapid rise of Pentecostal churches, Mt. Sion is well known by Catholics around Kampala, and its founder-pastor, who preaches in full liturgical vestments, has been made a monsignor. By emphasizing themes of healing and prosperity, as Pentecostals do, it has supposedly stemmed some of the tide from Catholicism toward those churches. It manages simultaneously to draw on Pentecostal styles, but to frame them at times around very Roman and traditionalist Catholic formats, and to indigenize Catholicism by both reinforcing traditional beliefs about ancestors’ continuing roles in people’s lives, and providing an alternative message of healing and protection. As one Ugandan there put it, “it keeps our children from going away to the Pentecostals, and does some of what they do, but in a more Catholic way. It is bringing back our youth who had gone out.” The Archbishop of Kampala is supportive of the shrine.

Mt. Sion is said to draw persons of all religions from all over Uganda and even from neighboring countries. Its New Year’s services are crowded, as are the overnight SSangaalo (a Luganda term for a place where one goes to find God) vigil on the last Saturday of each month.

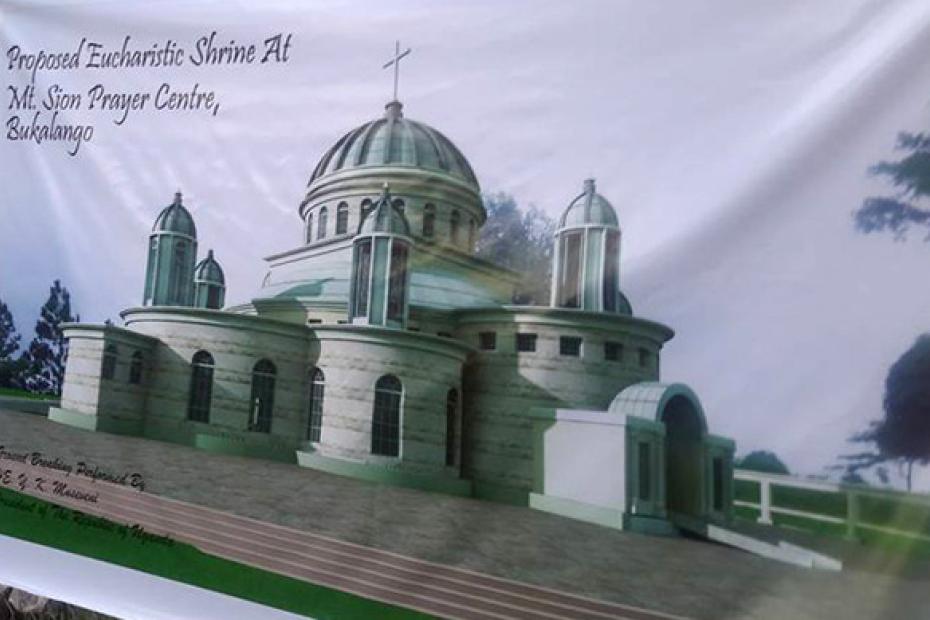

In September 2014, Mt. Sion broke ground for a large church on the site with a dedication by President Museveni.

- 1This essay is written on the basis of a visit Mt. Sion in January, 2014, with interpretative help from two Kampala Catholics, one of whom was a parish catechist.