More than any other means, the visual, tangible element of Ukrainian Catholic culture bears witness to the Church’s “in-between” status, between Roman West and Orthodox East, at least in Lviv. The music chanted in churches is distinctively Slavic, and the form of the liturgy is distinctively Byzantine.1 Time is marked with a distinctively Eastern calendar of saints. But in Ukraine, particularly in Lviv, Western and Eastern legacies are very much visible, even after a period of Byzantinization. A visit to any of the major older churches of Lviv makes the difference apparent, and shows just how much Lviv was a crossroads of cultures. Extraordinary Baroque—quintessentially Roman style—churches, legacies of Polish and Austro-Hungarian rule, are decorated with the iconostasis screens and other elements that aim to mark them as Byzantine.2 The Gothic Roman Catholic St. Elizabeth Church has been re-purposed as a Greek Catholic church, with icon screens. Even the major Orthodox church there, the Dormition Church, has a Roman-styled interior and an iconostasis.

The Eastern, Byzantine tradition has its own very powerful aesthetic language. In keeping with the Byzantine tradition, Ukrainian Catholic church interiors are meant to inspire a sense of awe and even an image of heaven. An iconostasis, a large, resplendent, typically golden wall of icons, is typically the focal point of attention in Ukrainian Catholic churches. It marks a border between heaven and earth, between the sanctuary and the body of the church, and its icons provide a glimpse into the heavenly realm, an image of divine presence. At its center is a royal door, and its sides feature two smaller doors, for the deacons and acolytes. At the lower level it features images of the Theotokos, the Mother of God; Jesus; St. John the Baptist; and the Church’s patron saint. Icons are not merely decorations, but are regarded as windows to the divine.

Ukraine is also known for its distinctive wooden churches, tserkva, which precede that baroque tradition. Few survive today, though some have been copied in the diaspora. In a number of instances, the ones that survived lasted because they were made into small museums of atheism. In Lviv, many were gathered in a park as part of a Soviet folkways museum to showcase “backward,” pre-Soviet culture.

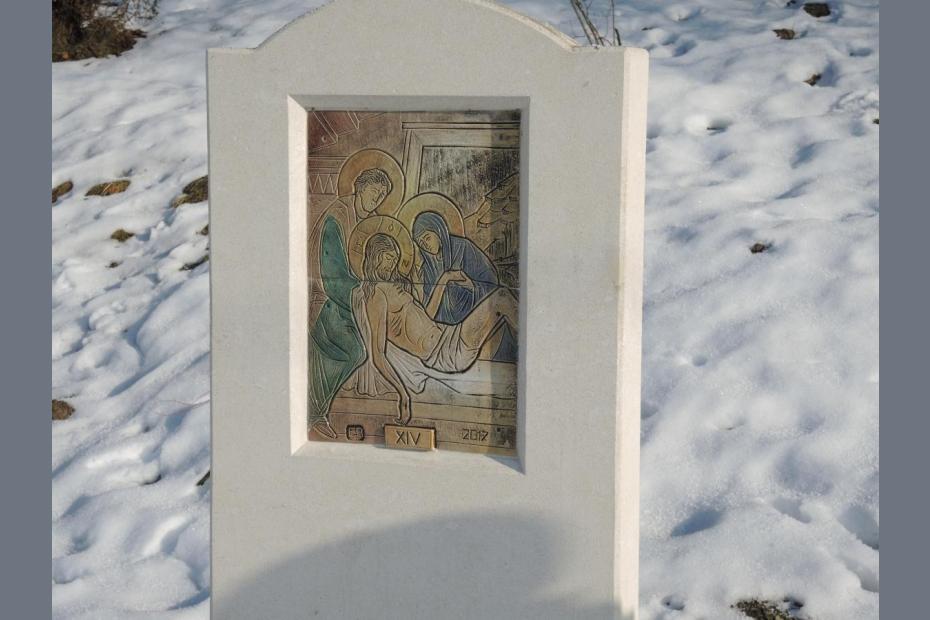

The flatness of the iconographic style of Byzantine art is in marked contrast to the effervescent, flowing character of Baroque art. But in the course of Byzantinization in the Church in recent decades, the UGCC has opted away from Western artistic models toward Byzantine ones. One typically sees no statues and only icons in many newer churches. But even as the Church chooses the path of Byzantinization, not all believers want to let go of Western religious practices, and Western forms pop up with some frequency, e.g. at crèche scenes in churches and in Western-styled statues of the Virgin.

Icons play an important role in Catholic home life. In a 2015 survey, Pew Research Center reported that 94% of Ukrainian Catholics said that they had icons or other holy articles at home, 81% that they light candles in churches, and 74% that they wear religious symbols.3 On the latter front, at least, religious symbols were rarely visible on people during a 2017 visit to Lviv at Easter, but may more commonly be worn discreetly.

- 1The distinction here derives from the fact that Greek/Byzantine music is monophonic, whereas most Slavs moved to (Western) polyphonic music. In contrast to most of Western liturgical music, it remains solely vocal, without musical accompaniment.

- 2In Galicia many of the now Greek Catholic churches were once Roman Catholic ones, serving the large Polish population until the end of World War II.

- 3Pew Research Center, “Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe,” (May 10, 2017) 75, http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2017/05/15120244/CEUP-FULL-REPORT.pdf.