The nativity scene or crèche, called in Italian the presepe or presepio, brings to life the story of the Nativity as told in the canonical as well as apocryphal gospels. The presepe (pl. presepi), which literally means “in front of the crib,” has been an important feature of Christmas celebrations in Italy for centuries. Appearing in churches, piazzas, and living rooms on December 8 (the Feast of the Immaculate Conception), presepi remain up until after January 6, or Epiphany, the feast associated with the visit of the Three Kings or Magi. While a presepe will always include figures of Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus, many nativity scenes surround the holy family with elaborate reenactments of traditional or contemporary life, complete with local buildings, streets, and pastimes. Presepi such as these are not just dioramas picturing a legendary event from ancient Palestine, but are mirrors of the known world.

Origins

The legendary origins of the presepe was a theatrical Mass performed by St. Francis in 1223 in the town of Greccio. As described by his biographers, Francis brought in a live ox and ass and a straw-filled crib as props to bring the Christmas story to life. Francis also performed his famous Mass not inside a church but outside in a wooded grove, using the local environment to recreate the Nativity as a living event. It was in the 16th century, during the Counter-Reformation, that the tradition took hold of the popular imagination and presepi began appearing in private homes as well as in churches. The golden age of presepe art was in 18th-century Naples under the sponsorship of the Bourbon royal family, when presepi became “must-haves” among the Neapolitan nobility, with collections comprising hundreds of figurines and taking up entire floors of palazzi. Naples still remains arguably the world-center of presepe art, with workshops that have been in continuous operation for centuries.

Presepi at Home

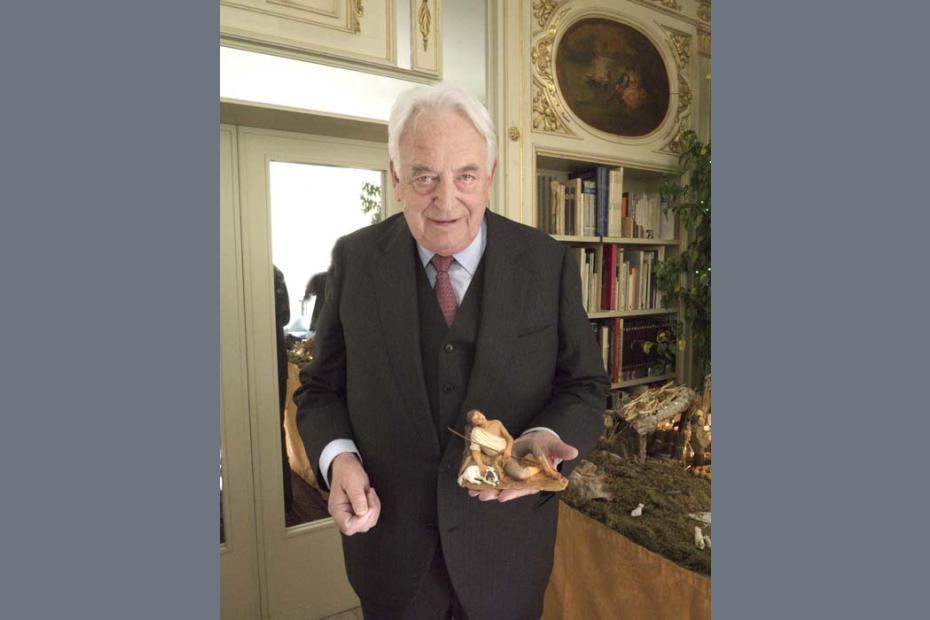

In many parts of Italy today, particularly in the south, building the presepe remains a part of Christmas ritual, though increasingly the presepe is being replaced by the Christmas tree. To set up the presepe is to place Christianity’s founding moment in one’s living room—and even to build it there. Francesco, a Neapolitan law student, says that his family sets up two presepi each year, one that is just the Nativity and the other that is a large, exuberant ensemble in the Neapolitan style, taking over the family dining room table and relegating the family to meals in the kitchen. Setting up the presepe is traditionally man’s work, says art historian Maria Toscano, interviewed outside the San Martino Museum above the Bay of Naples. Her father used to build the family presepe each year, but hammering together the nativity scene is now her job. Franco Artese, the maestro from Grassano who was commissioned to build the Vatican’s 2012 presepe, says he started building presepi after many years of watching his father construct the family nativity scene. Finally, at age 18, he could get his own hand in. And Carlo, a retired attorney in Rome, assembles a large presepe in his living room every year, peopled with exquisite 8-inch figurines that have been passed down in his family for generations. Part of the backdrop is made from grapevines that he cut in the family vineyard in Lecce when he was a child. The vines are symbolic of the Eucharist, but also tied to his own family. His set always includes a water feature—an annual engineering challenge—with real goldfish. Water, a presepe staple, is also symbolic as a reference to baptism. After the holidays Carlo returns the goldfish to the pet store. He takes particular care with the cave of the Nativity, even down to Joseph’s carpentry tools hanging on the cave’s back wall. For Carlo, as for many, the presepe is a ritual that connects him to his family’s past, his culture, and his faith.