Every year, for four or more days surrounding Pentecost, one million people descend on an otherwise isolated, whitewashed town on the edge of a national park in southern Spain. The town, nearly empty most of the year, exists almost entirely for the sake of a grand annual pilgrimage to celebrate Nuestra Señora del Rocío, Our Lady of the Dew, whose shrine is there. The feast culminates in a wild, raucous procession of her statue into the plazas, beginning in the deep of the night following Pentecost. The feast, and the town, are known as El Rocío, the Dew. Her devotees, the pilgrims, are known as rocieros.1

The experience of El Rocío begins on the trail, or often in home town rituals before hitting the trail. Before and after those four days in El Rocío, members of the many brotherhoods dedicated to her travel by horse and wagon for at least a day or two along designated trails to the town. These colorful horse and wagon trains are a sight in themselves.

Though Pentecost is hardly ignored—it is commemorated with a large scale, formal, televised Mass in the plaza, typically presided over by one of Spain’s leading bishops—the draw for pilgrims during these days is Nuestra Señora del Rocío, who is celebrated for days in a particularly Andalucian way. The combination of revelry, all night celebration, costumes, singing, dancing, conviviality and devotion to the Virgin make it unlike anything else in the Catholic world. For anyone who expects that a pilgrimage, especially a Marian pilgrimage, is necessarily somber, the particular exuberance of these days at El Rocío is hard to comprehend. Conversely, anyone who thinks that the celebrations of the week are only an excuse to socialize, eat and drink, act out Andalucian cultural identity, and play out intercity rivalries would be sorely mistaken. All these things weave with devotion at El Rocío.

Given its location in sandy marshlands, El Rocío has little other reason for being than as a stage for the annual pilgrimage. Only about 1,000 people live there year-round—inhabitants describe it as “empty” when the many brotherhood houses are closed—though the population can swell to 10,000 with visitors during vacation weekends and off-season visits from brotherhoods dedicated to El Rocío.2

The town of El Rocío has something of a movie-set feel, particularly during the four days of the feast when cars are almost entirely excluded and horses and pedestrians take over the unpaved, sandy streets. Add to that the ubiquity of colorful flamenco style dresses on women and traditional corto costumes of men, and the stage set is nearly complete. Most buildings in town, like the main church, are less than 50 years old, but those buildings, costumes, food, horsemanship, songs, design, carriages and the like all bring idealized aspects of traditional Andalucian culture into devotional practice.

The Sanctuary of Our Lady of Rocío, commonly referred to as the ermita, or hermitage, sits at the edge of a small lake, and the rest of the town extends northward from there. Picturesque houses for members of the 124 brotherhoods of El Rocío, and a larger number of private dormitory houses, all with white stucco facades and red tile roofs, surround the plazas where people enjoy themselves for days and where Nuestra Señora del Rocío is carried in such a frenzy on the night of the feast.

The brotherhood houses in El Rocío are marked by the an open, grilled cove in front of each to display their simpecado, the banner with an image of the Virgin on it, in the elaborate carriage that has brought it to town. This is often a place to gather for prayer, such as a Rosary or a Salve in the evening. The houses are also designed for conviviality, and they (and the plazas) are where pilgrims spend the bulk of their waking time, rather than in the sanctuary. In all types of houses, living space is structured to accommodate as many people as possible. Most houses also have a covered patio out front and/or a nice courtyard inside, where local foods, sherry and songs are shared. In front of almost every building are hitching posts for horses. Huge fields around the town accommodate not only cars, but campers. Some families or groups of families own homes as well, and brotherhoods rent many of these for their overflow. The number of hotel rooms is quite small. Almost everyone who does not belong to a hermandad has to camp out or drive in from some distance for the day.

The devotion and pilgrimages there date to the 13th century, but in the last century—particularly since the 1960s—participation in it has grown enormously. Modernization and prosperity has not undermined the event. Instead, it has enabled the event to grow significantly. One interviewee, from a local family who has attended for generations, said that as it began to expand beyond the local area, “the media came; television, famous actors, singers, bullfighters came. The media made it famous. But it is still for people from Andalucia.” Indeed, many things about the feast, especially its ebullience, remain puzzling even to Spaniards from other parts of the country.

Historical background

The history of El Rocío as a place of devotion dates to the 13th century, when a hunter is said to have discovered a statue of the Virgin Mary in a tree in the marshlands that form the delta of the Guadalquivir river. A small hermitage was built there, at the crossroads of several ancient roads. In 1653, under the title Nuestra Señora de las Rocinas, she was named the patron saint of the town of Almonte, about 15 km north, and the Brotherhood of Almonte began making annual pilgrimages there each September. In 1759, the date was shifted to Pentecost weekend.

Seven towns within a one or two day walk from El Rocío joined the pilgrimage during its first 150 years, and four more towns and cities further away in Andalucia joined them over the course of the 19th century. The number of active brotherhoods spiked during the Second Spanish Republic, but the real growth has been in the last five decades.

A mid-19th century account of the pilgrimage describes it as a combination of fun and piety, though at the time the accommodations were primitive.3 Attendance in the 19th century is said to have been in the range of 6,000-10,000 people. In 1919, the Holy See approved the request of the people for a formal coronation of the image, after which the image that had previously looked more like a peasant woman in 19th-century clothes took on the clothes and crown of a queen. About 20-30,000 people are said to have attended, most of whom camped out or stayed in their wagons. Those numbers were fairly consistent up to 1958, when a new road was built from Almonte, and participation doubled. In 1964, a new sanctuary was conceived to replace the older, damaged sanctuary. It was dedicated in 1969 and its facade and tower were completed by 1980. The elaborate gold retablo at the altar was dedicated in 2006. An urban plan was developed in 1972 to radically expand the village.4 In 1979 700,000 people attended, and in 1984 and 1985 there were a reported 1.5 million people.5 Pope John Paul II visited El Rocío in June 1993. Even during the economic crisis post-2008, people report that attendance was not affected. In 2018 the Hermandad Matriz simply claimed that a million or more people would visit the town sometime between Friday and Monday.

The sacred and the secular, together in most distinctive ways

El Rocío is known in Spain precisely for its particular combination of sacred and secular, for bringing together long days and nights of social enjoyment (in a particularly Andalucian fashion), with the fervent, even raucous devotion in the night procession. The romería to El Rocío may be the grandest by far, but many Andalucian towns have their own, smaller-scale romerías, with processions, fireworks, bands and a pilgrimage to some nearby shrine. Whether on the front patios drinking and eating, or in the crush of things at night around the palio of the Virgin, El Rocío can alternately seem like the least and the most fervent feast in the Catholic world.

Spanish television accounts of El Rocío typically highlight the most raucous parts of the feast, especially the young men scaling the gate on Monday at 3 a.m., fighting to get at the Virgin’s palio, or carrying platform, to carry her. Media coverage is often at least implicitly critical, locals say—it features only the most raucous parts, or, lately, critiques the involvement of animals like oxen and horses as inhumane—so it doesn’t do justice to the full experience. One visitor from Madrid said that she was afraid, having seen TV images, that it would be “too crazy.” Having spent a few days in El Rocío, she said that she would have to tell all her friends that it’s not at all what they imagine. She was surprised to see how much more there is to it from a devotional point of view. “Raucous at times, yes, but it’s much more than that. It’s clean and joyful. My friends have it wrong.”

Interviewees and others frequently alluded to it not being religious enough by referencing that some small number of people might come primarily to drink. The raucousness of the nighttime procession probably also contributes to that perception, given how incongruous it can seem to be jostling that way to carry a placid, regal, maternal statue.6 But the question of how El Rocío is or isn’t “religious enough” seems more complicated. In four days spent throughout town, while people could frequently be seen with a glass of wine in front of them, drunkenness was never a visible problem. Any raucousness was confined to that night.

The village of El Rocío may seem strange as a pilgrim destination, as a “sacred site,” precisely because it is such a “secular”—in the original sense of that word, lay-oriented—place. Unlike many religious shrines in Europe, it is not managed by clergy or a religious order. A lay brotherhood does that, in cooperation with “filial” brotherhoods and the Church. Despite having clear religious markings, and a beautiful sanctuary-shrine, El Rocío is not a town of monasteries or convents. The sanctuary is not even a parish church, but is the chapel of the Hermandad Matriz, a lay confraternity. A monastery does not serve as the normative model of religiosity at El Rocío. In this regard it stands out from major European Marian shrines, and from regional Spanish ones like Montserrat, a Benedictine site; Guadalupe (Extremadura) and Aranzazu, Franciscan sites; or even from Pilar, the pilgrimage site at Zaragoza’s Cathedral-basilica.7 This is especially remarkable if we recall that at the end of the 20th century, Spain was still home to 900 convents and monasteries — 60% of the world’s total.8 None is to be found in El Rocío: this town is entirely lay-residential, and the presence of the many lay brotherhoods—lay residences—is the closest equivalent.

Neither is El Rocío a site renowned for miraculous appearances and physical healings, or full of ex-voto images to commemorate these. Religious goods are sold at the sanctuary, but there is not the same abundance of religious goods stores as at some other major shrines.

The organizers of the feast, and many interviewees we spoke with there, have no difficulty with the idea that the experience is not centered so continuously around formal prayer to the Virgin. Several said that the place to really understand its meaning is in the streets. Asked what they would say outsiders who think this is all a little crazy, some young men replied, “There are people who come for the reasons they come, but there are [more] people who know what this means… there are people crying on el camino [the walking part of the pilgrimage], or when they get here. [A few] come here because other friends are coming, and they come just to try, and maybe they are going to drink… the people who really like this place don’t behave that way.” Others cautioned that while the raucous parts stand out in many people’s memory, it’s important to remember that there are many rules that are respected, as a matter of honor—rules about the order for brotherhoods to arrive in town, to appear before the Virgin, and more. These are observed, many stressed, as a matter of “respect.”

A woman answered the same question by saying, “There is so much. It’s hard to explain. You can come to make a promise, for a sick person, or for a member of your family who is dead, for a personal motive. For me, the most important thing is to see her [the Virgin] in the street… When I saw [my hermandad] introduced, I cried and wept and don’t know why. I was overcome. My favorite part is to see her in the street and to speak with her and to see that she is looking at me.”

One man, a leader of a key brotherhood, described the days at El Rocío, as he was preparing to leave with his brotherhood after that raucous night procession, as an experience of “organization, disorganization and reorganization again.” That insight speaks to some sacred power of religion and the divine breaking into the world in a not-always-orderly way. The frenzy of men clamoring at the sanctuary’s iron gate to get to the Virgin’s palio, or when carrying it, suggests a different kind of prayer than many are accustomed to: Like the costaleros who carry the heavy platforms in Seville’s Holy Week processions, though in far less disciplined fashion, the men of Almonte who carry the palio “pray with their muscles” and with their fatigue as their offering.9 They and onlookers pray by means of their joy and the creation of a spectacle.

The devotion, however much officials try to shift attention to Pentecost, signals the very powerful role that Mary has in Andalucian Catholicism. Jesus takes a visually minor role, as a tiny figure hardly visible in a much larger woman’s arms. He is known as El Pastorcito, the Little Pastor, while she is, among other titles, La Pastora. Beyond the powerful fact of motherhood—she is hailed as the Mother of God—the feast does not frame Mary’s life in the context of Jesus’s life as devotions like the Seven Sorrows or the Rosary do. People who spoke did not refer to Jesus explicitly when they talked about why they came, and often spoke about the image as more than a representation: “She floated above us in the plaza,” or “She looked at me.”

On display

Collectively, with its costumes and rituals, the pilgrimage to El Rocío—the wagon train, the presentations at the sanctuary, the horsemanship, the singing and socializing on patios, the night procession—is an unabashed performance, with an invitation to join in. “Performance” does not imply that it is inauthentic, but speaks to a cultural desire to embody and perform their devotion and identity.

El Rocío is a culture on display—indeed, it is a culture of display—but it certainly differs from a folklore festival. It is distinctively Andalucian in terms of food, costume, horsemanship, and many of the collective rituals of devotion. But there are no organized exhibits of Andalucian life; no special concerts or shows. The costumes, horses, food, wine—and the Virgin herself—root the participants temporarily in their shared Andalucian culture.

Even as El Rocío has become a magnet for all Andalucians, El Rocío is also a place where even more localized identities are crucial and played out. A number of the acclamations of Viva! that are proclaimed—¡Viva la Virgen del Rocío! ¡Viva la Reina de las Marismas! (the Queen of the Marshes), ¡Viva la Patrona de Almonte! (the Patroness of Almonte)—tie the Virgin to a more particular geographic place than Andalucia. Each brotherhood inhabits its own town’s house, and stands up for its town. There is an element of inter-town competition and certainly hierarchy among them (they are presented at the sanctuary, for example, in order of hierarchy), but El Rocío’s brotherhood houses are also places of welcome. As an outsider, I was repeatedly welcomed into circles for food and conversation, and into brotherhood houses. Food and wine were always part of the welcome, without hesitation. For members of brotherhoods, participation is in part an intense experience of belonging in the context of a specific brotherhood, and of belonging to something larger.

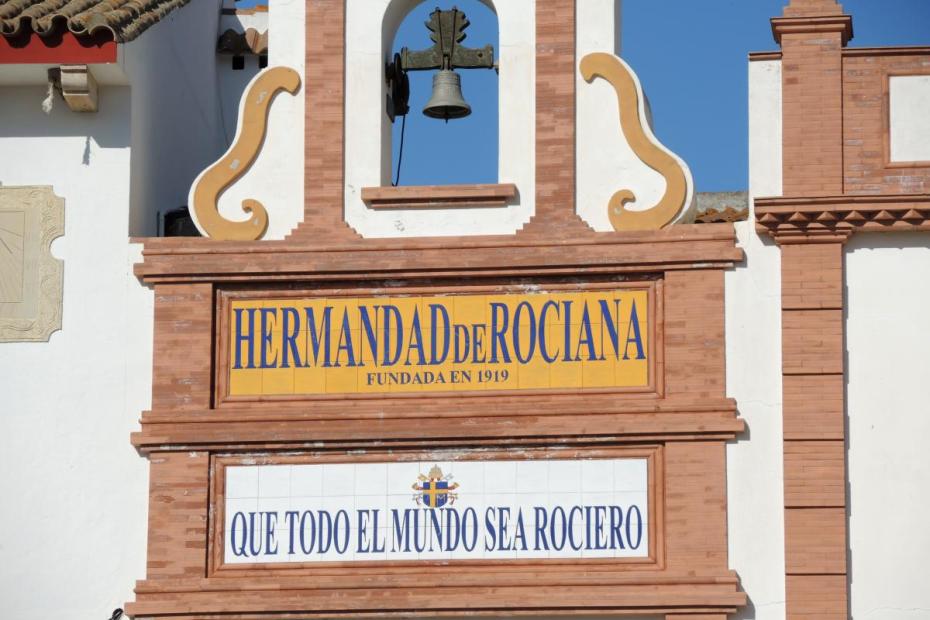

Performative as it may be, El Rocío isn’t about performing an identity for outsiders. Very few outsiders find their way there. Hotel space is minimal, and reservations are extremely difficult to get. In this sense it is opposite to Lourdes or Fatima, which are full of huge hotels. Almost everyone in the few tiny hotels in El Rocío had some connection to the towns and the feast. Other Spaniards do know about the feast through television broadcasts that focus on the mad, late night scramble to the palio (leading television stations pay for access to the best spots for cameras). The small number of hotel rooms assures that the feast will remain centered on local and regional customs, people, and needs, not turned into an internationally-oriented site. One restaurant owner said he was closing his restaurant for most of the feast because help was too hard to find, and he wanted this year to participate in it and enjoy it. Pope John Paul II’s line, “¡Que todo el mundo sea rociero!” —"Let the world be rocieros!"—may be a repeated refrain there, but nonetheless, as a man quoted above said, “it is still for people from Andalucia.”

El Rocío’s horses and costumes can certainly make it seem like an exercise in nostalgia, and the pilgrimage is often described as a family time. But interviewees acknowledged that a lot had changed in family life, and said that this was not about turning the clock back. There were many people there who were divorced, I was told, but the brotherhoods had adapted. One very devout woman reported, “When you come here, even if you are separated, or part of your family is missing, you make a group with friends.” Gay couples occasionally held hands in the streets and plazas, and I encountered even a few visibly transgender people. Neither did it separate out Catholics from non-Catholics easily, as I was told that participation in his confraternity was something “even for atheists.”

At feasts like La Tirana in Chile, interviewees have often said that young women are the driving force for drawing young men, but here young men insisted that they come because they want to, and that it is often young men who encourage their girlfriends to come along. In a Spain that is secularizing, young people still perceived El Rocío as something that is growing, and vibrant, much bigger than it was in their grandparents’ time, and people clearly enjoy being part of that.

- 1Observations and interviews for this description of El Rocío took place during the 2018 romeria, or pilgrimage. Special thanks to Teresa Dolado Martin for her guidance and assistance, and to the Hermandad Matriz for providing access at a number of key moments.

- 2Each year, too, on a much smaller scale, Almonteños—people from the town that sponsors the feast—celebrate a “Rocio chico,” a celebration that began in 1813 to commemorate the town’s protection and survival during the Napoleonic invasions. Almenteños promised that the day would be marked in perpetuity as an act of thanksgiving. Juan Ignacio Reales Espina, El Rocío: Una Realidad de Fe (Sevilla: Hermandad Matriz Ntra. Sra del Rocío de Almonte/Padilla Libros Editores y Libreros, 2018), 19.

- 3Serafín Adame y Muñoz, Feria del Rocío, 1849, as cited in Faraco and Murphy, “El Rocío: La Evolución de un Aldea Sagrada,” in El Rocío: Análisis culturales e históricos, ed. Michael D. Murphy and J. Carlos González Faraco (Diputación de Huelva: 2002), 64.

- 4Faraco and Murphy, “El Rocío: La Evolución de un Aldea Sagrada,” 74.

- 5Attendance figures are from Michael Dean Murphy, “Class, Community and Costume in an Andalusian Pilgrimage,” Anthropological Quarterly, 67 no. 2 (April 1994): 52. Other attendance figures, and their sources, are charted in J. Carlos González Faraco and Michael D. Murphy’s “Masificación Ritual, Identidad Local, y Tiponomia en El Rocío” in El Rocío: Análisis culturales e históricos, 96.

- 6Notably, the image of the Virgen del Rocío has two facets, though only one is visible at the feast. In El Rocío, she is dressed in lush, embroidered gold fabric, like a queen. When she is brought back to Almonte, as she is every seven years, she is dressed as La Pastora, The Shepherdess. The style of her clothes is more formal than a shepherdess would dress in the fields, but the image signals a notably different understanding of who she is to the people there. On the sharply contrasting representations manifest of N.S. del Rocío as Queen and Shepherdess, see Michael D. Murphy and J. Carlos González Faraco, “Reina y Pastora: las Representaciones Duales de la Virgen del Rocío” in Vírgenes, Reinas y Santas: Modelos de Mujer en el Mundo Hispano, Tercer Encuentro Iberoamericano de Religiosidad y Costumbres Populares, ed. David González Cruz (Huelva: Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Huelva y Centro de Estudios Rocieros, 2007), 337-354.

- 7J. Carlos González Faraco and Michael D. Murphy “El Rocío: La Evolución de un Aldea Sagrada” in El Rocío: Análisis culturales e históricos, 59.

- 8Tony Judt, Postwar: a history of Europe since 1945 (New York: Penguin, 2005), 774.

- 9Manuel Siurot, La Romería del Rocío, Huelva (n.p. 1918), 28-29, as translated and quoted in Murphy, “Class, Community and Costume,” 55.